Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

Reviewing the Porcupine Tree Discography —

with Steven Wilson (1999)

Steven Wilson is one very talented and prolific guy. In addition to being lead guitarist, vocalist, producer and primary composer for Porcupine Tree, Wilson has a number of other projects. He plays in a quirky pop band called No Man, a wild instrumental psychedelic project named IEM (The Incredible Expanding Mindf*ck), the ambient Bass Communion, and also various other production gigs and guest appearances. Clearly Wilson is a very busy fellow. Despite all of the other creative outlets, Wilson’s primary focus is Porcupine Tree. With the “band” now having been making music for nearly a decade, and with five studio albums plus numerous other releases to their credit, it seems that a look back at their recorded output is a good idea. Reviewing the Porcupine Tree discography is a true delight as the albums represent some of the best music that has been made during the 90s. The journey through the five studio CDs is also rather exhilarating, as one can watch Wilson (and later on the entire band) progress and grow in leaps and bounds.

by David Ashcraft, Published 2000-05-01

Exposé had the opportunity to catch up with Steven Wilson during the May-June ten-date tour of the US and Canada and asked him about the background behind each of his recordings. Here then, is the inside story of Porcupine Tree...

Our story begins in 1989 with Steven Wilson working at a computer for a large aerospace firm. His paychecks are all invested in building up a home studio set-up that essentially allows him unlimited studio time. Thanks to a record deal with his band No Man, Wilson is able to leave the 9-to-5 world for something far more creative. Meanwhile, as a side project, Wilson started writing and recording songs at a rapid pace while playing all of the instruments himself. As he puts it, “Porcupine Tree started out as a labor of love simply because I had access to the studio equipment.” The two 90-minute tapes that he recorded, Tarquin’s Seaweed Farm and The Nostalgia Factory, came to the attention of Richard Allen of the psychedelic magazine Freakbeat and he became an instant convert. Allen also founded Delerium Records, and his first signing was Porcupine Tree. The reaction to the release of the tapes was very positive and Delerium ultimately asked Wilson to combine the best of the two tapes into a double album (later a single CD) entitled On the Sunday of Life, which came out in 1991.

Our story begins in 1989 with Steven Wilson working at a computer for a large aerospace firm. His paychecks are all invested in building up a home studio set-up that essentially allows him unlimited studio time. Thanks to a record deal with his band No Man, Wilson is able to leave the 9-to-5 world for something far more creative. Meanwhile, as a side project, Wilson started writing and recording songs at a rapid pace while playing all of the instruments himself. As he puts it, “Porcupine Tree started out as a labor of love simply because I had access to the studio equipment.” The two 90-minute tapes that he recorded, Tarquin’s Seaweed Farm and The Nostalgia Factory, came to the attention of Richard Allen of the psychedelic magazine Freakbeat and he became an instant convert. Allen also founded Delerium Records, and his first signing was Porcupine Tree. The reaction to the release of the tapes was very positive and Delerium ultimately asked Wilson to combine the best of the two tapes into a double album (later a single CD) entitled On the Sunday of Life, which came out in 1991.

Cut to Steven Wilson: “The thing that I like about that release is that it is ridiculously diverse.” The album does in fact veer from tuneful pop to wild psychedelic excursions with some spacey experimental interludes tossed in for good measure. Wilson pointed out that debut albums are special since there are no preconceptions of the band, and this allows for tremendous freedom regarding future direction. “I’ve got fond memories of On the Sunday of Life. When I re-mastered it a couple of years ago I still found that I was really enjoying it.” The press in the UK was extremely enthusiastic and Wilson suddenly found that a solo project to amuse himself had become more successful than his “real” band, No Man. And thus Porcupine Tree was launched...

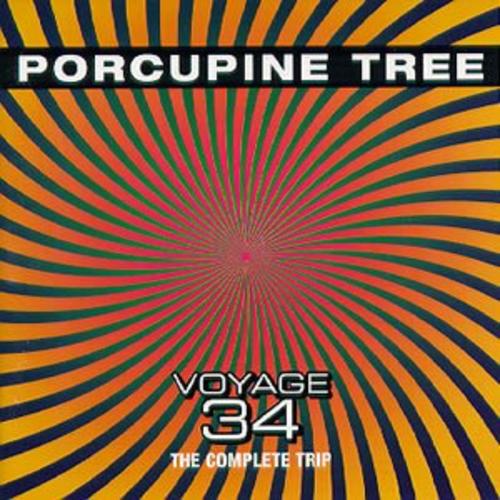

Wilson had plans to follow up his first release with another double album, but Allen asked him to split up the material for release since double albums are notoriously difficult to market. The first piece that came out in late 1992 was a thirty minute CD single entitled Voyage 34 which shocked many people due to the shift in mood from the first album. An aural depiction of an acid trip, Voyage 34 combined Orb-influenced electronics with Porcupine Tree’s fluid guitar style and rock direction. The result was a mind-blowing track that became an indie smash hit and really brought Porcupine Tree into the public awareness. The track has aged well and in fact was played live during the recent tour. It will be re-released shortly in both the original as well as re-mixed versions for those who missed it the first time around.

Wilson had plans to follow up his first release with another double album, but Allen asked him to split up the material for release since double albums are notoriously difficult to market. The first piece that came out in late 1992 was a thirty minute CD single entitled Voyage 34 which shocked many people due to the shift in mood from the first album. An aural depiction of an acid trip, Voyage 34 combined Orb-influenced electronics with Porcupine Tree’s fluid guitar style and rock direction. The result was a mind-blowing track that became an indie smash hit and really brought Porcupine Tree into the public awareness. The track has aged well and in fact was played live during the recent tour. It will be re-released shortly in both the original as well as re-mixed versions for those who missed it the first time around.

The next CD release was 1993’s Up the Downstair, with the title coming from the 60s era documentary on LSD that had been sampled in Voyage 34. Wilson describes the album as “a consolidation of what Porcupine Tree were going to be about,” and “the first cohesive Porcupine Tree statement.” The album clearly showcased Wilson’s rapidly evolving songwriting skills as well as his searing, effects-laden lead guitar. The result was a disc with a wide variety of styles from melodic acoustic tunes to space rock to even a few elements of trance. Wilson considers the album to “have some good songs on it” while maintaining “kind of a dreamy psychedelic feel.” His only regret is that the production isn’t quite up to his later standards since “I was playing all of the instruments myself and having to rely on things like drum machines more than I would have liked.” The album also marked the first appearance (on one track each) of ex-Japan keyboard player Richard Barbieri and old schoolmate Colin Edwin on bass. This was to foreshadow the formation of the actual band two albums later.

The next CD release was 1993’s Up the Downstair, with the title coming from the 60s era documentary on LSD that had been sampled in Voyage 34. Wilson describes the album as “a consolidation of what Porcupine Tree were going to be about,” and “the first cohesive Porcupine Tree statement.” The album clearly showcased Wilson’s rapidly evolving songwriting skills as well as his searing, effects-laden lead guitar. The result was a disc with a wide variety of styles from melodic acoustic tunes to space rock to even a few elements of trance. Wilson considers the album to “have some good songs on it” while maintaining “kind of a dreamy psychedelic feel.” His only regret is that the production isn’t quite up to his later standards since “I was playing all of the instruments myself and having to rely on things like drum machines more than I would have liked.” The album also marked the first appearance (on one track each) of ex-Japan keyboard player Richard Barbieri and old schoolmate Colin Edwin on bass. This was to foreshadow the formation of the actual band two albums later.

The next Porcupine Tree release (in 1995) was a ground-breaking effort that brought a new audience to the band but also saddled Wilson with baggage that he is still trying to rid himself of to this day. The “problem” was that The Sky Moves Sideways contained a 35 minute suite, soaring guitar solos, and some blissed-out music with multiple allusions to space. This resulted in countless comparisons to Pink Floyd, and even Wilson concedes that “the Floyd influence is pretty heavily ingrained” and that the album was “veering dangerously close to the Floyd blueprint.” In reality it is far better than anything that Pink Floyd have recorded since The Wall and is a true classic. The album takes the listener on a 65-minute journey through space but is also grounded with some superb songs such as “Stars Die” and the smoldering instrumental, “Moonloop.” By the way, the former track was left off the UK version of the album (Wilson calls it “the biggest mistake I’ve ever made”) so you should search out the US version. Wilson comments on the success of the two tracks mentioned above: “I don’t think that it’s coincidental that they were the first two pieces where I used real drums and other musicians.” The interaction of the quartet (with drummer Chris Maitland) convinced Wilson to form a band both for playing the music live and also for the recording of subsequent albums. The direction for future recordings would also take a decidedly non-Floydian direction since Wilson has said “I hate the idea that I’m living in the shadow of someone else”. As he puts it, “ever since then with the band we’ve made it our mission to try and be as original as we possibly could be and transcend influences so that people just start talking about Porcupine Tree”.

The next Porcupine Tree release (in 1995) was a ground-breaking effort that brought a new audience to the band but also saddled Wilson with baggage that he is still trying to rid himself of to this day. The “problem” was that The Sky Moves Sideways contained a 35 minute suite, soaring guitar solos, and some blissed-out music with multiple allusions to space. This resulted in countless comparisons to Pink Floyd, and even Wilson concedes that “the Floyd influence is pretty heavily ingrained” and that the album was “veering dangerously close to the Floyd blueprint.” In reality it is far better than anything that Pink Floyd have recorded since The Wall and is a true classic. The album takes the listener on a 65-minute journey through space but is also grounded with some superb songs such as “Stars Die” and the smoldering instrumental, “Moonloop.” By the way, the former track was left off the UK version of the album (Wilson calls it “the biggest mistake I’ve ever made”) so you should search out the US version. Wilson comments on the success of the two tracks mentioned above: “I don’t think that it’s coincidental that they were the first two pieces where I used real drums and other musicians.” The interaction of the quartet (with drummer Chris Maitland) convinced Wilson to form a band both for playing the music live and also for the recording of subsequent albums. The direction for future recordings would also take a decidedly non-Floydian direction since Wilson has said “I hate the idea that I’m living in the shadow of someone else”. As he puts it, “ever since then with the band we’ve made it our mission to try and be as original as we possibly could be and transcend influences so that people just start talking about Porcupine Tree”.

Signify was released in 1996 and in many ways is a transitional record. While it is the first Porcupine Tree album to feature a group, it essentially placed Barbieri, Edwin, and Maitland in the role of session musicians. As Wilson put it: “I’d written all the songs, I’d demo’d all the songs, and they were just replacing my parts almost.” Despite the lack of arranging or compositional input from the band, Signify is a strong release with some great songs. “I think that there are some of the best pieces we’ve ever done on that record” muses Wilson. He is referring to “Every Home Is Wired” and “Waiting” in particular, which he views as establishing a “sound” that is unique to Porcupine Tree. The album is transitional in the sense that Wilson was “getting more interested in singing and good songs, and less interested in long drawn-out spacey instrumentals.” As such it is a perfect link to his most recent work.

Signify was released in 1996 and in many ways is a transitional record. While it is the first Porcupine Tree album to feature a group, it essentially placed Barbieri, Edwin, and Maitland in the role of session musicians. As Wilson put it: “I’d written all the songs, I’d demo’d all the songs, and they were just replacing my parts almost.” Despite the lack of arranging or compositional input from the band, Signify is a strong release with some great songs. “I think that there are some of the best pieces we’ve ever done on that record” muses Wilson. He is referring to “Every Home Is Wired” and “Waiting” in particular, which he views as establishing a “sound” that is unique to Porcupine Tree. The album is transitional in the sense that Wilson was “getting more interested in singing and good songs, and less interested in long drawn-out spacey instrumentals.” As such it is a perfect link to his most recent work.

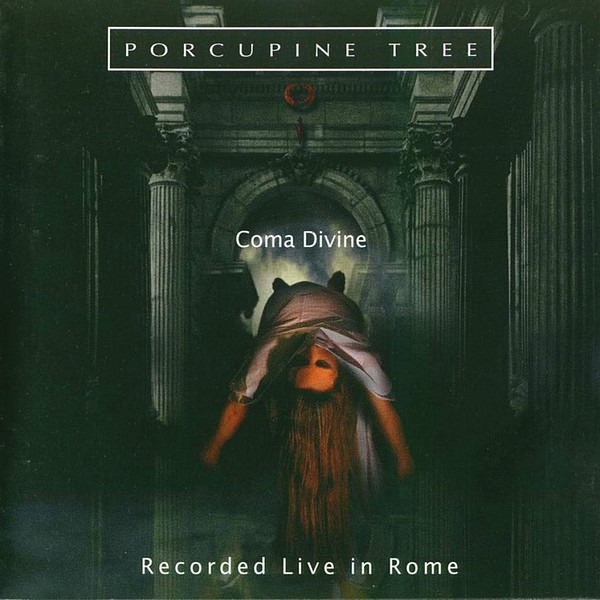

It became clear that as Porcupine Tree kept evolving that they would eventually outgrow Delerium Records. It was a mutual parting since the label simply couldn’t afford the type of studio budget that the band required. Wilson’s parting gift to Delerium in 1997 was the live album, Coma Divine, which was recorded during a three-night stand in Rome (one of the several European cities where Porcupine Tree had grown quite popular). The album features material from all four studio releases, with versions of “Radioactive Toy” and “Not Beautiful Anymore” that develop into powerful extended jams. As Wilson puts it, “Many of the versions of the songs are incredibly different, with much more dynamic.” It is an outstanding record and an excellent document of the strength of the band as a performing unit. As anyone who has seen the band can attest, they are extremely powerful in concert and they do complete justice to the studio versions, often improving upon them in the process.

It became clear that as Porcupine Tree kept evolving that they would eventually outgrow Delerium Records. It was a mutual parting since the label simply couldn’t afford the type of studio budget that the band required. Wilson’s parting gift to Delerium in 1997 was the live album, Coma Divine, which was recorded during a three-night stand in Rome (one of the several European cities where Porcupine Tree had grown quite popular). The album features material from all four studio releases, with versions of “Radioactive Toy” and “Not Beautiful Anymore” that develop into powerful extended jams. As Wilson puts it, “Many of the versions of the songs are incredibly different, with much more dynamic.” It is an outstanding record and an excellent document of the strength of the band as a performing unit. As anyone who has seen the band can attest, they are extremely powerful in concert and they do complete justice to the studio versions, often improving upon them in the process.

The band’s 1999 release is entitled Stupid Dream, and it is quite possibly the best album that they’ve ever done. It is absolutely jam-packed with tremendous songs, superb instrumental excursions, and it features crystalline production. It is also very consistent from track to track and even features three tracks with serious radio potential (the warped pop of “Piano Lessons”, and haunting beauty of “Pure Narcotic”, and the shimmering aura of “Stranger By The Minute”). As Wilson puts it, “Stupid Dream is the culmination of working towards getting the group sound for the first time, and with songs that I’m really proud of.” He acknowledges that the album contains several pieces that are more straight-forward pop songs and notes: “The best albums for me fuse great songwriting, experimental production, and good playing. They stand the test of time.” While Wilson’s tunes have a great sense of melody and addictive hooks, they are also filled with loads of subversive psychedelic touches that make them successful on multiple levels. Wilson has gone for the “classic, timeless sounds of Hammond organ and strictly analog keyboards on the new CD since digital synthesizers tend to date things rather badly.” The guitar playing on the new release (and in fact all of the Porcupine Tree releases) is also deserving of special recognition. Wilson consistently delivers majestic, inventive, and melodic yet intense solos that to many listeners are somewhat reminiscent of David Gilmour’s playing. Wilson’s actual influences are early Peter Green, Robert Fripp, and Jimi Hendrix, but he has certainly assimilated and transcended these influences to arrive at his own distinct style. If you are interested in hearing consistently superb guitar playing you owe it to yourself to check out Porcupine Tree!

The band’s 1999 release is entitled Stupid Dream, and it is quite possibly the best album that they’ve ever done. It is absolutely jam-packed with tremendous songs, superb instrumental excursions, and it features crystalline production. It is also very consistent from track to track and even features three tracks with serious radio potential (the warped pop of “Piano Lessons”, and haunting beauty of “Pure Narcotic”, and the shimmering aura of “Stranger By The Minute”). As Wilson puts it, “Stupid Dream is the culmination of working towards getting the group sound for the first time, and with songs that I’m really proud of.” He acknowledges that the album contains several pieces that are more straight-forward pop songs and notes: “The best albums for me fuse great songwriting, experimental production, and good playing. They stand the test of time.” While Wilson’s tunes have a great sense of melody and addictive hooks, they are also filled with loads of subversive psychedelic touches that make them successful on multiple levels. Wilson has gone for the “classic, timeless sounds of Hammond organ and strictly analog keyboards on the new CD since digital synthesizers tend to date things rather badly.” The guitar playing on the new release (and in fact all of the Porcupine Tree releases) is also deserving of special recognition. Wilson consistently delivers majestic, inventive, and melodic yet intense solos that to many listeners are somewhat reminiscent of David Gilmour’s playing. Wilson’s actual influences are early Peter Green, Robert Fripp, and Jimi Hendrix, but he has certainly assimilated and transcended these influences to arrive at his own distinct style. If you are interested in hearing consistently superb guitar playing you owe it to yourself to check out Porcupine Tree!

Where can we expect the unpredictable Wilson to head next? As he states: “I never set out to make a left field turn-it’s only when the album is released that the fans tell ME that there has been a change in direction!” The next Porcupine Tree album is already two-thirds written and it should contain at least three tracks that are over ten minutes long as well as a number of shorter pieces. Wilson plans on bringing in other musical colors just as he did with the excellent flute and sax contributions from British jazzer Theo Travis on Stupid Dream. “I want to do loads and loads more of that such as dulcimer, banjo, orchestra, and some of Colin’s ethnic instruments.” Wilson has enlisted Dave Gregory of XTC for some string arrangements and the album could come out as soon as Spring.

Porcupine Tree is a truly great band with a very strong back catalog that is well worth exploring (there will be a double CD compilation out soon on Delerium with lots of rare stuff as well as studio material). The band has absorbed and transcended their influences. As Wilson says, “We’re as influenced by what we’ve done in the past as we are by other musicians.” They are now on the forefront of a movement that continues to progress while maintaining some of the best elements of 60s and 70s psychedelic rock. If you haven’t yet discovered them, the time is now!

Filed under: Interviews, Issue 19

Related artist(s): Porcupine Tree, Richard Barbieri, No-Man, Steven Wilson / I.E.M., Theo Travis, Colin Edwin

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Release: Tashi Wada - What Is Not Strange?

Updated 2026-02-24 14:56:16 - Artist: Tashi Wada

Updated 2026-02-24 14:54:34 - Release: Greg Segal - Maintain!

Updated 2026-02-24 00:38:03 - Review: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Published 2026-02-24 - Review: Nektar - Mission to Mars & Fortyfied

Published 2026-02-23 - Review: Jaime Rosas - Tres Piezas de Rock Progresivo

Published 2026-02-22 - Release: Kevin Kastning & Bruno Råberg - Across Tall Rain

Updated 2026-02-21 00:42:08 - Review: Gary Husband - Postcards from the Past

Published 2026-02-21 - Release: Daniel Crommie - Februa

Updated 2026-02-20 14:23:17