Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Reviews

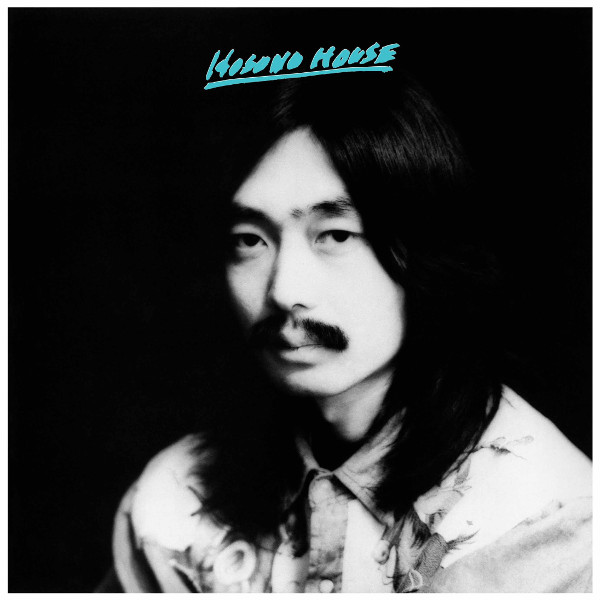

Haruomi Hosono — Hosono House

(Light in the Attic LITA 173, 1973/2018, CD)

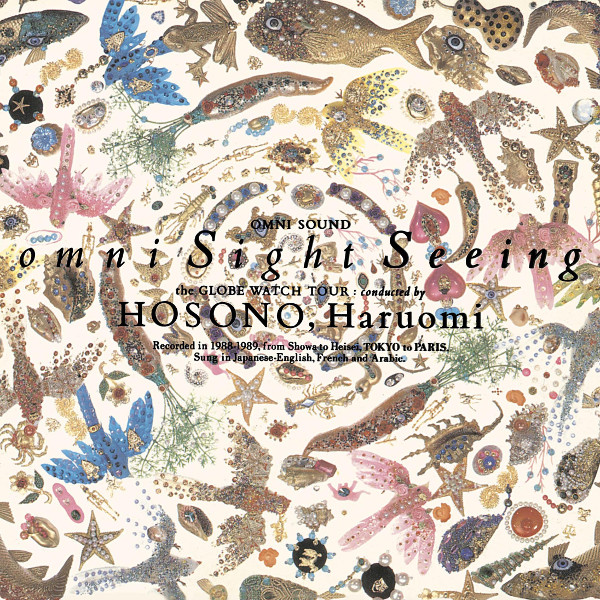

Haruomi Hosono — Omni Sight Seeing

(Light in the Attic LITA 171, 1989/2018, CD)

Hosono & Yokoo — Cochin Moon

(Light in the Attic LITA 174, 1978/2018, CD)

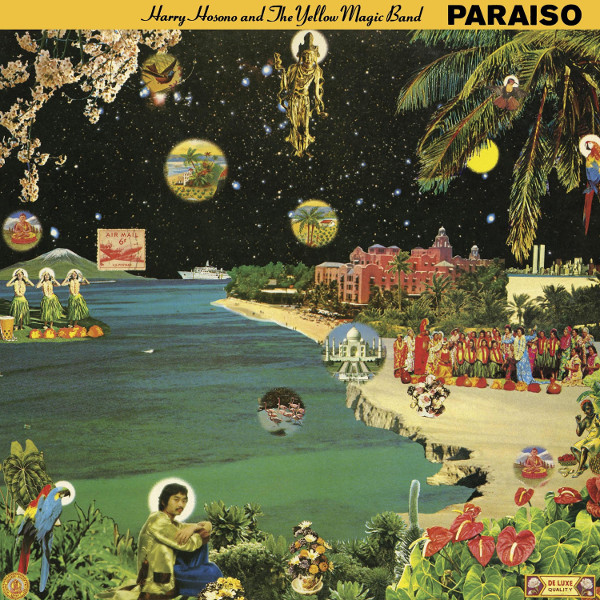

Harry Hosono and the Yellow Magic Band — Paraiso

(Light in the Attic LITA 172, 1978/2018, CD)

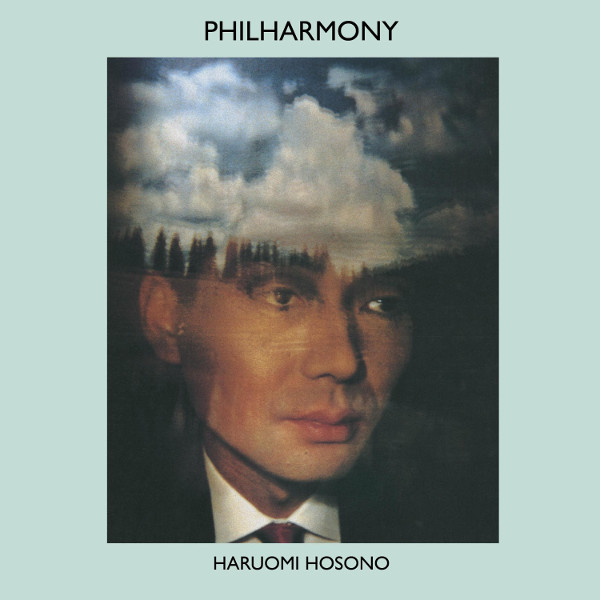

Haruomi Hosono — Philharmony

(Light in the Attic LITA 170, 1982/2018, CD)

by Jon Davis, Published 2018-11-06

When Yellow Magic Orchestra’s first album came out in 1978, listeners around the world were treated (many for the first time) to creative music from Japan, something that wasn’t just copying styles from Europe and the US. They took the electronic pop of Kraftwerk and, with tongue in cheek and great style, infused it with Japanese elements and infectious humor, gleefully both skewering and honoring the clichés Westerners had of Asia and doing it in music that was as sophisticated as it was accessible. What most listeners didn’t know is that YMO was not a trio of young newcomers, but a collective of three experienced veterans of rock, pop, classical, and experimental music. Ryuichi Sakamoto has achieved the greatest fame in the years since then, with dozens of movie soundtracks and acclaimed albums both as a solo artist and in collaboration with others. But at the time of YMO’s founding, it was Haruomi Hosono who was the best known in Japan. In fact, it was Hosono’s album Paraiso, credited to Harry Hosono and the Yellow Magic Band, that brought Sakamoto, Hosono, and Yukuhiro Takahashi together. Hosono’s career began in the 60s with a psychedelic rock band called Apryl Fool, and in the 70s he led Happy End, which was one of the most prominent original bands in the country at the time. Many of his albums were never released in the US, so this new series of reissues by Light in the Attic serves to bring them to a wider audience.

His first solo album came out in 1973, and it presents one of the themes that is prominent in his style: a fascination with American country music. This thread also played out in much of Happy End’s music, and in both cases, he writes original music with Japanese lyrics in the style rather than covering American songs. Hosono House presents tunes that range from acoustic twang with pedal steel to funky workouts with fuzzy psychedelic lead guitar. There are also hints of tropicalia, another of his fascinations that would come to the fore on later albums. Several tracks feature horns in arrangements that bridge R&B and Big Band styles, and there are some unexpected harmonic choices that will keep the interest of listeners who look for sounds that are out of the ordinary. In short, aside from the Japanese lyrics, Hosono House can sit comfortably next to albums of the time by such artists as Jackson Browne, Warren Zevon, and even Elton John.

Now we skip ahead to 1978 and Paraiso. When Hosono recruited Ryuichi Sakamoto and Yukihiro Takahashi for his newest solo album, there apparently wasn’t a plan to continue the partnership, but something clicked, and one year saw the release of four albums featuring the trio: Hosono’s Paraiso, Sakamoto’s Thousand Knives, Takahashi’s Saravah! and YMO’s self-titled debut. The artist credit on Paraiso is, as previously mentioned, Harry Hosono and the Yellow Magic Band, reflecting Hosono’s fascination with earlier eras of pop music where a suave leader fronted a band — check out the cover of his earlier Bon Voyage Co. album. His sense of humor, especially regarding Western stereotypes of Japanese music, is reflected in a couple of the covers presented. He revises the early-50s novelty tune “Japanese Rhumba” and Wanda Jackson’s 1958 hit “Fujiyama Mama.” (Note that “Japanese Rhumba” is mistakenly credited to Glenn Miller on some websites — it’s actually by Jerry Miller, who was sometimes billed as “G. Miller.”) Hosono embraces the silliness of these tunes, making them his own and treating them no differently than his original songs, and in so doing subverts the Orientalism of the originals. The personnel is extensive on the album, featuring many players and singers beyond the YMO trio (and in fact Takahashi is only on one track), providing guitars, ukuleles, steel drums, percussion, and much more. There are some hints of the electronic sounds that YMO would be known for, especially on the wonderful “Shambala Signal,” which features gamelan-like bells and a propulsive beat. On the whole, the album has a breezy tropical mood that’s quite a lot of fun, coming off like a much more creative and sophisticated version of Jimmy Buffett’s kitschy island music.

1978 also saw the release of Hosono’s Pacific solo album (not reviewed here) as well as a collaboration with graphic artist Tadanori Yokoo called Cochin Moon. This album is a very different thing than Paraiso, though it also exhibits some of the tropical theme found on other albums — at least visually. The idea here is that the album is the soundtrack for a movie of the same name, and judging by the cover, it’s a Bollywood romance, though the music is unexpectedly experimental and electronic. It features Hosono and Sakamoto on keyboards, with programming by Hideki Matsutake; Yokoo produced the artwork. The music is generally on the sparse side, with rhythmic sequences, lots of fun electronic noises, minimalistic percussion, and melodies played on synths with very interesting tones. There are sections of shimmering bell-like tones and sounds like distant thunder, random blips and bleeps, washes of white noise, occasional vocal samples (in the days before actual samplers), atmospheric echoes, and some hints of Indian percussion. Cochin Moon is heavily sequenced electronic music that sounds nothing like Tangerine Dream, which is an accomplishment on its own! This album is quite enjoyable and highly recommended to fans of experimental electronic music.

The next few years were mainly occupied with producing five Yellow Magic Orchestra albums, plus touring around the world with the band. Philharmony (1982) was Hosono’s next solo release, and it tends much more to a technopop style, though with plenty of experimental and artistic touches. There’s a version of the old Italian song “Funiculì, Funiculà” done up with synthesizers and choppy vocal editing; there are quirky danceable tunes like “Platonic” which are not far off the YMO standard; and there are nice instrumental tunes which feature weird effects and odd combinations of sounds, like “Luminescent Horaru” with its interlocking mallet-like parts, odd skritchy noises, and erratic melodic synth. It is very much along the lines of Bill Nelson’s non-ambient albums of the 80s (and of course, Nelson would work with both YMO and Takahashi in the near future). Philharmony is unapologetically a pop album, but a very creative one with several non-poppish diversions, and listening to it today, it is certainly of its time, though it doesn’t really sound dated.

Finally, we come to Omni Sight Seeing, a 1987 album that came after the initial breakup of YMO and Hosono’s first forays into soundtrack work, as well as several other solo albums. The sound here features seamless integration of real instruments from around the world into a basically electronic context, with accordion and qanun on most tracks, and vocalists singing in a variety of languages including Japanese, English, and Arabic. Hosono was perhaps not the first to incorporate Middle Eastern sounds into electronic music, but his take on it is idiosyncratically his own, and makes sense given his past work. Instrumental aspects tend to dominate, with vocals used a coloration more than in a conventional song form. In addition to real instruments, sampled and emulated sounds take equal status, all going into his sonic mix. While many of the tracks feature steady beats, Hosono keeps things rather sparse and textural, not going for blatant dancefloor clichés. Once again, he includes a cover from the pre-electronic age, Duke Ellington’s “Caravan,” which fits right in with the Middle Eastern milieu of the album. Some of the album’s best moments are seemingly unassuming, like the lovely instrumental “Korendor,” which features a rhythm track reminiscent of birds and crickets and a mostly minimalistic piano part. Omni Sight Seeing is another great piece in the giant puzzle that is Haruomi Hosono’s recorded legacy, and another fine album that stands the test of time admirably. Having these albums more readily available to an audience outside Japan is wonderful, and should cement Hosono’s worthiness to stand next to his bandmate Ryuichi Sakamoto as one of the greats of modern Japanese music.

Filed under: Reissues, 2018 releases, 1973 recordings, 1989 recordings, 1978 recordings, 1982 recordings

Related artist(s): Ryuichi Sakamoto, Yukihiro Takahashi, Haruomi Hosono

More info

http://lightintheattic.net/artists/2475-haruomi-hosono

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Review: Sterbus - Black and Gold

Published 2026-03-03 - Release: Janel Leppin's Ensemble Volcanic Ash - Pluto in Aquarius

Updated 2026-03-02 15:06:51 - Release: Janel Leppin - Slowly Melting

Updated 2026-03-02 15:05:27 - Release: Alister Spence - Always Ever

Updated 2026-03-02 15:04:11 - Release: Let Spin - I Am Alien

Updated 2026-03-02 15:02:41 - Review: Falter Bramnk - Vinyland Odyssee

Published 2026-03-02 - Review: Exit - Dove Va la Tua Strada?

Published 2026-03-01 - Review: Steve Tibbetts - Close

Published 2026-02-28 - Release: We Stood Like Kings - Pinocchio

Updated 2026-02-27 19:24:02 - Release: Stephen Grew - Pianoply

Updated 2026-02-27 19:20:11 - Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25