Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

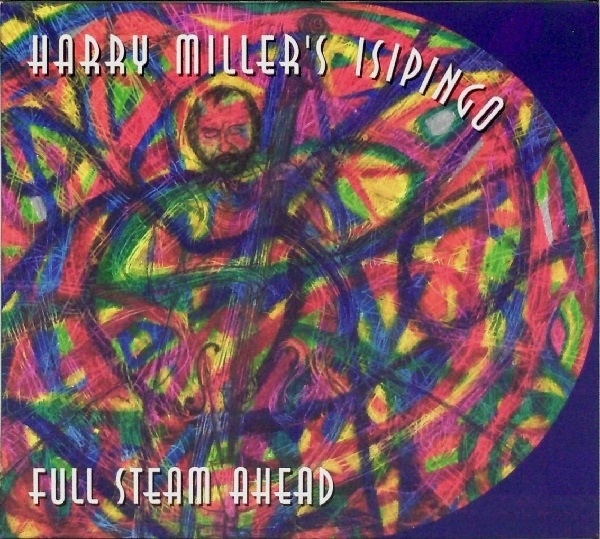

Tape Head Redux —

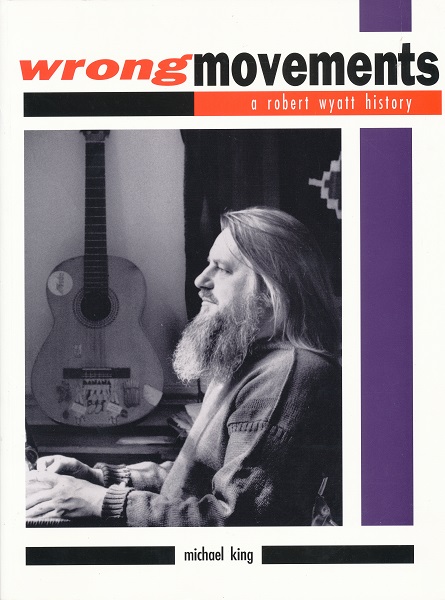

The Mike King Interview

I recently had the privilege of speaking to Reel Records impresario Mike King regarding his fascination with British jazz, the process of tape archiving and re-mastering, and his upcoming efforts supporting the February 23rd Queen Elizabeth Hall evening celebrating the life and music of Nucleus founder Ian Carr. Exposé is indebted to Mike, the author of the important Robert Wyatt chronology Wrong Movements, for bringing us up to date on his current exploits and his strong passion for independently produced music.

by Jeff Melton, Published 2010-07-01

Please tell us how you became so enamored with the British free jazz/Canterbury scene. Can you name a few pivotal recordings that defined your mind set, and why they did?

Please tell us how you became so enamored with the British free jazz/Canterbury scene. Can you name a few pivotal recordings that defined your mind set, and why they did?

In Toronto, where I was born and raised, there was an underground radio station named CHUM-FM. I was 13 when I began listening, so that would’ve been 1970. This is how I first heard the recordings of King Crimson, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd, ELP, Yes, much hard rock, and many songwriters. In those days you could hear The Who back to back with Captain Beefheart or Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage,” and nobody thought it was wrong. Obviously, this was before capital (the system, not the label) set its teeth into chewing all popular music, and its means of delivery, into profit-margin-only conditions. By 1975, CHUM-FM and most every other free-format radio in America was dead, but the years thereafter were the second major phase of my lifelong musical education; that is to say as an MLK devotee, my love of African-American music, namely 20th century jazz (the first being AM radio pop). On the ground back then, you could actually go downtown to Sam the Record Man and A&M and find alphabetical racks labeled “British Imports.” I began working, if only to buy myself records, especially British, German and Italian Imports. Interestingly, in Canada during the mid-70s, Progressive rock found a sizable concert and record buying public, and I wore the jeans and t-shirt. The other high school boys could have their Black Sabbath and Deep Purple – gimme my Genesis and Gentle Giant, both of whom I saw in 1974. I’ve gone through a great deal of other musical experiences since then, but those were my roots, embarrassing, as they seem to me today. Anyway, through Egg, I picked up on Hatfield and the North and Caravan through recommendations by friends. Looking back now, I was enamored with contrapuntal music making, like Le Orme and PFM. The pivotal records then were the ones by King Crimson, Van der Graaf Generator, and McDonald & Giles, but there was so much more besides. Certainly a pivotal experience that defined my mindset was listening to psalms played on the Anglican church organ between the ages of 8 and 13. This was where I first encountered improvisation. Not only did I hear it, but I vividly remember sensing the spirit of free expression through the musical figures. So again, back in 1970 when I heard Egg perform Bach’s “Toccata & Fugue in D Minor,” replete with sensitive rock backing through my father’s short-wave radio, the die was cast. I’m not who I was then, obviously, and only a fraction of what I listened to in my teens remains welcomed by my heart today, but McDonald & Giles has remained a desert island disc ever since.

How are sales for your label? Where is your target market? How are the archive releases being received in general? It seems that the British press is beginning to take note.

How are sales for your label? Where is your target market? How are the archive releases being received in general? It seems that the British press is beginning to take note.

We continue to sell our titles, often including the so-called back catalog, so it’s great to know that people are becoming aware of what we’ve produced and what we are interested in. Many of our titles are only limited to a thousand copies, so once they’re gone, this will be the music’s listenership. I must confess that I simply cannot think in terms of ‘target market’ given the galaxy that is today’s internet, to say nothing of my preference for individuals finding their own path to whatever music moves them. To the heart of the matter, I don’t like to tell somebody what they should like or listen to. I was recently on the receiving end of such arrogance and naturally it arrived from an ignoramus — so his dictate was a non-starter.

Reel Recordings exists as an alternative to “commercial CD manufacture,” as it presents recordings that capture a musical performance with minimalist computer intervention. In terms of potential releases, merits such as wider cultural significance, intrinsic sonic attributes, and spirited performances with a strong element of improvisation generally attract my ear. If commerce was my first priority then I simply could not do what I love to do.

The reception to the label in general has been very positive. We’ve been welcomed by many supportive listeners, and reviews have been uniformly appreciative. If by British press you mean Jazzwise and Wire, then yes, they’ve both reviewed our releases positively, but it’s baffling that Britain remains largely indifferent to its recorded heritage of jazz and improvised music. It seems omni-downloads and file sharing have virtually sealed this matter of indifference. But yes, as for Jazzwise, it was great to just read that Jon Newey included our Splinters Spilt the Difference in his Top 10 Reissues and Archive Best of 2009. The vitality and importance of Jazzwise cannot be understated, especially for the young generation of musicians.

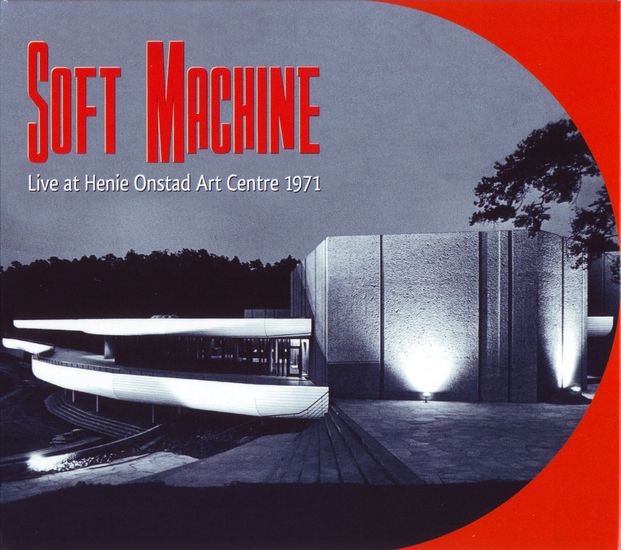

Please tell us about your great find for the new Soft Machine archive. How long did it take for you to confirm and actually hear the quality of the gig? What was the condition of the master tapes and what kinds of obstacles did you encounter in securing rights?

Please tell us about your great find for the new Soft Machine archive. How long did it take for you to confirm and actually hear the quality of the gig? What was the condition of the master tapes and what kinds of obstacles did you encounter in securing rights?

Live at Henie Onstad Art Centre 1971 could not have been possible without the help of close friends. I knew that Steve Feigenbaum at Cuneiform was sent four reel-to-reel copies direct from the Henie Onstad masters, as well as CD-R copies for convenience. I got computer copies of the CD-Rs and didn’t think much of them. But when [Mike’s wife] Miki and I traveled to France last year to see Greaves/Blegvad resuscitate their Kew Rhone masterpiece, and the Canterbury legends Hugh Hopper, Phil Miller, Didier Malherbe, and Alex Maguire, we found ourselves sharing a nice late night meal with Hugh. When I told him about some recordings of the early 1970 quintet, he suggested the Henie tapes, adding, “I think you’ll find the playing is better.” That got my brain swirling, so when we got home, I asked Steve to send up the reels, but nothing could have prepared me for the shocking difference in sonic playback experienced between the tapes and the CD-Rs. Serendipity arrived when we quickly found that the Henie Onstad Art Centre was also excited to have Reel produce their amazing recording. The tapes we used were first-generation copies from Henie’s masters, and they were in superb playback condition. Anyway, Hugh was in, as was Elton [Dean]’s wife Marino. Mike [Ratledge] was enthusiastic, and particularly keen about the fact that it is a direct-to-two-track ambient recording, or as he put it “ah, the classical technique.” That left Robert [Wyatt], and he was keen also, adding “I like listening to me on drums now.”

Which of your releases are you proudest of releasing, and why?

Which of your releases are you proudest of releasing, and why?

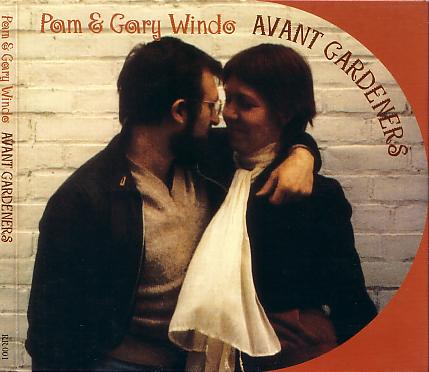

Pam and Gary Windo’s Avant Gardeners, with the deepest respect for a depressingly long list of musicians whose music we’ve cared for who have shrugged off their mortal coil. I confess, to my ears and my musical heart, absolutely nobody else played saxophone like Gary Windo. I’ve heard his likeness, and that’s because he was a walking encyclopedia of all things that could be attached to a mouthpiece. He was equal parts Archie Shepp and Junior Walker in a volcanic whirlwind of playing power. So, when I conceived of Reel Recordings as a venture, it was with the private and concert recordings of Pam and Gary Windo that Gary bequeathed me with which I hoped could be made to work as a program. Going over those recordings involved a mix of responses, but certain sections did seem to suggest themselves as such. To create tracks from these tapes became my personal tribute to an all-too-brief friend. I’m hoping to release the complete Steam Radio Tapes sessions in the future.

In contrast to the making of Avant Gardeners, a great benevolent discovery happened upon when Trevor Watts contacted me, saying that he’d amassed quite a tape library over the decades. He sent me a brief list and a few suggestions for possible release. This is how I discovered Trevor’s recordings of Splinters. My heart skipped a beat upon being reminded that Splinters was the meeting of another tenor hero, Edward ‘Tubby’ Hayes, with Kenny Wheeler, Trevor, Stan Tracey, Jeff Clyne, and the legendary drummers Phil Seamen and John Stevens.

Last year Jeff suffered a fatal heart attack at age 72, which was a terrible shock. He was one of the nicest people I’ve spoken with and he was very supportive in developing our Splinters CD.

Can you describe a particular recording you are still pursuing in hopes of releasing in the near future?

Ultimately, what I would love to do is a DSD CD release, whereby the tape master is played/recorded directly into an uber-resolution Direct Stream Digital Recorder. But I need to find such a tape! The other problem is that SACD is dead as a format. A few other tapes are in the rear-view mirror, pointing forward. There’s an unreleased Mouseproof record from May ’69 that makes much rock music wilt — that one is only a matter of time. And I’m committed to pulling together another double Miller / Coxhill release — there’s a lot to consider musically. I’ve also re-mastered several jaw-dropping reels once owned by Tony Oxley. Another dream tape would be the award winning 1969 Montreux concert by Alan Skidmore’s Quintet (Skid / Wheeler / Taylor / Miller / Oxley). Or anything with Joe Harriott.

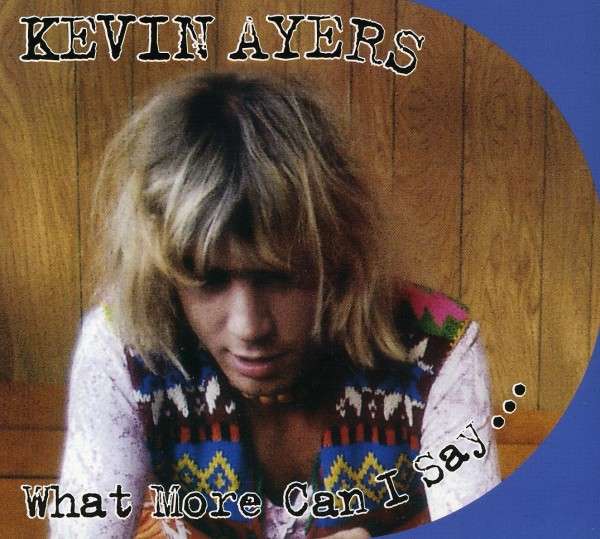

I was fortunate enough to review your recordings of Mike Osborne, Kevin Ayers, and Steve Miller with Elton Dean. Each of these is a unique gig which really places the listener in an intimate setting to hear the music. Is this intimacy for each of the recordings a part of what you want to provide the listener, or a happy side effect of the mastering process?

I was fortunate enough to review your recordings of Mike Osborne, Kevin Ayers, and Steve Miller with Elton Dean. Each of these is a unique gig which really places the listener in an intimate setting to hear the music. Is this intimacy for each of the recordings a part of what you want to provide the listener, or a happy side effect of the mastering process?

Intimacy is the bull’s eye, by which I mean that I subscribe to audiophile mastering engineer Steve Hoffman’s motto of seeking to sustain the “breath of life” within a recording. The biggest problem is that most consumer playback systems cannot retrieve what has been encoded on said disc or record. The art of playback is very complex and requires research/knowledge, a little good fortune, and, unfortunately, considerable monies. That $99 CD player through powered mini-monitors (add $99) is only going to grip the trunk of the musical tree, not present it as the lifelike experience it often is. Playback responsibilities lay where mine for the recording end. Conventional remastering for archival recordings tends towards imparting something sonically larger than the musical experience, and in extreme it can actually demolish it. I cannot work with an approach that proves to be a greater experiential failure. Having worked with analogue tape since the mid-seventies, in one capacity or another, has greatly informed my listening experiences. So when I hear a well recorded analogue reel-to-reel the very last thing I wish to do is compress it! And yet this for years has been a fait accompli as an ‘industry standard.’ EQ? Well that depends... Mostly all a great tape requires is accurate/tonally neutral amplification and properly built speakers. The rest is a pure musical experience, which is intrinsically intimate and individual.

Please describe in your words the specific benefits of using the glass-mastering process. Have audiophile authorities presented any opinions as to the clarity of the sound based on the process you use?

There’s an inconvenient truth that the CD industry does not want to know about, so much so that they barely acknowledge the very existence of glass mastering! In my research, I’ve never encountered a CD broker or a pressing-plant manager that is even aware of the glass-mastering speed that is used in the lab. It’s off the radar. The ‘mother stamping’ standard is no longer x2, nor x4, but x8 and greater. The data compression cuts made against real time adds up substantially in increased work volume and profit for the plant. They’re treating the CD as a data product that works commercially in computers, cars, and mini-systems, so why not compress the data? Who cares, except those pesky self-described audiophiles? Except, discs manufactured from a x12 glass master are sonically compromised, and there is simply no way of knowing what has being done during this important mastering stage when you read about the next CD you’re looking to buy. This is why we pay a premium for single-speed real-time glass masters, simply because I’ve really no idea what’s going to happen to my master otherwise! So it functions as a guarantee as we’ve used three separate pressing plants across our catalog. For the release itself, this means that the music appears from a cleaner background with greater detail, impacting the listening experience positively. By the way — the same holds true should you ‘treat’ new CDs to rid them of ‘release mould compounds’ by using quality cleaners (Walker Audio, Auric, Finyl etc). There’s a positive tip for every dedicated headphone (not earbud) listener reading!

To answer your second question, I’ve not sent a single package of Reel Recordings titles to Stereophile, Absolute Sound, nor any of the British nor international counterparts, largely because I hold no delusion that any reviewer would be interested in their value musically. I know that sounds dismissive, but they’re reviewing a wealth of classy contemporary recordings, as I occasionally read. Besides, Reel Recordings was not conceived as an audiophile label, only as an exclusive home for analog recording documents.

To switch gears a bit, how did the Wrong Movements book get started?

To switch gears a bit, how did the Wrong Movements book get started?

It all came about through Hugh Hopper, whom I met when he was on tour in Canada with Lindsey Cooper’s Old Moscow, back in October ’89. I conducted an interview with Hugh and produced a radio program, “An Hour with Hugh Hopper.” At the end of our interview, he put into my hands a couple of contacts: one was for the Canterbury Nachterne fanzine, which was run by Manfred Bress out of Germany, and the other Phil Howitt’s Facelift.

I wrote away to Phil and got a copy of Facelift, and I believe it was the second issue. And inside it mentioned the subscription rate, but also that if you wished to contribute an article you’d get a free subscription. Always one to take advantage of a bargain, I decided to write a little article about Robert Wyatt. I wrote Phil and he was enthusiastic, then I wrote back saying this effort entails a lot of details if we are going to really examine Robert’s career, and asked, “Would you mind making it a feature issue?” Phil wrote back excited and approving. I wrote back a couple weeks later saying: “No – it’s going to be a book.” This was inspired by what I was told by my father, which was: If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right. That led to literally beginning by chronicling the recording dates from record sleeves, then of course chronicling the bootleg tapes. I began to researching and set myself up as a sort of data base, in that I tapped into the private archives of Phillipe Renaud, Manfred Brest, and many musicians whom I contacted. Everyone seemed to have a piece of the puzzle. The more the puzzle became complete, the more I realized that there is no completion to this! That’s how the ball got rolling and it took four years — conception to publication. This was done in the day when we had to rely on letters, and phone calls were exorbitantly expensive. It could not have happened without the technical work by Allan Huotari.

The book is out of print now, but if some publisher indicated some interest, would you be willing to republish and update?

No, not at all. This is what I assured Robert immediately after publication. We became friends, as much as people can be friends who live in different countries. Robert was always great to me, and I saw what all of this research and questioning was doing to him. It dawned on me about halfway through that here I was holding up a mirror to a musician who was not living life through looking in a rear-view mirror. He is very forward-thinking, and he’ll bring you down to ground quickly about any musical history. I realized I was causing some pain, and there were points where I asked myself: “Just what is it am I doing, and why?” which is a good thing, to re-examine your motives, anyway. In the end, on publication, I assured him that I wouldn’t continue this, that I wouldn’t shadow document him for the remainder of his life. I’m just grateful he’s always been receptive to the many calls over the years approaching him to consider for release those old recordings that have popped up. Robert turns everything into a laugh in the end.

The real successor to Wrong Movements, to my mind, is the CD-ROM for the Live at Henie Arts Center. Part of the motivation to do it was to contribute something of substance after Wrong Movements, and to consider a greater contextualization for both the music and recording process, which was off topic for the book.

The real successor to Wrong Movements, to my mind, is the CD-ROM for the Live at Henie Arts Center. Part of the motivation to do it was to contribute something of substance after Wrong Movements, and to consider a greater contextualization for both the music and recording process, which was off topic for the book.

I would also like to say that the greatest reward during my research in constructing the book were the personal friendships found with many of the musicians, and their kindness. Everyone was absolutely positive, and wanted to contribute however they could. This meant more to me than the actual book, in the end.

The Canterbury people have always been very gracious, particularly when I met them at the Progman festival in Seattle; it was just unbelievable.

Yeah! They are all very generous. They will give you their time, and even tolerate our obsessions: the proverbial quest to understand.

What I hadn’t realized is the extent to which Robert had really disassociated himself from his work prior to the accident. I hadn’t realized that he had thrown the baby out with the bathwater for everything pre-1973; he saw it as an alternate self, an adolescent self. I hadn’t appreciated that, and when I got to know him and got to hear why this was, it seemed a perfect human response to disassociate from some rather embarrassing gestures, which we may think of in a nostalgic way, but which he certainly doesn’t.

It’s his life, so you went into it with a great deal of respect, and the book still shows that, basically because of how it is constructed and all the feedback from the contributors. It still stands as a very important document of the scene.

That was part of the intent, to once and for all establish just what it was that happened in terms of public music making. The music press and media had continually put out unintentional falsehoods. You would read a journalist who said, “Robert recorded End of an Ear after he left Soft Machine.” That’s surmising, but it’s not truth. I thought maybe there should be a reference point where all this could be put down. And as somebody who has a love of history, I just applied that to this music.

It’s also a quest for accuracy, because of the gig list and the ordering of the gigs, and seeing things like Matching Mole opening for Soft Machine in France, which, obviously, when Robert saw that again, you can imagine his response. “Did you have to remind me about that?”

You caught that, did you? These are the things that were going down that we didn’t know about on this side of the pond.

Robert expressed one funny thing to me: What he appreciated about the book was that it established once and for all that he and his mates were well-involved with experimental music before they ever formed a beat group. Conventional chronology suggests that they came out of beat groups, meaning rock and roll groups or R&B/rock and roll. Neither the Wilde Flowers nor the original incarnation of Soft Machine were very good Beat groups.

Please tell me about the Soft Heap archive that you’ve released, Al Dente. Is this the first or second gig? You worked directly with Hugh to get this released, right?

Please tell me about the Soft Heap archive that you’ve released, Al Dente. Is this the first or second gig? You worked directly with Hugh to get this released, right?

It’s the first concert, and yes, Hugh was involved. It was done through a fellow named Roy Wilberham, who set up a reel-to-reel in the club. I made several attempts to get an acceptable sound on the recording, and I almost closed the door on it before I found the key to unlock a frequency balance that made it an appreciable listen. Thankfully it does play back better on some poorer systems, oddly enough.

I’ve always loved Alan Gowen’s playing and his approach to composition, and I was very fortunate to have seen him perform twice with National Health (Roundhouse 10/76 with Bruford, and Toronto 11/79). I was inspired to make this happen by knowing there was a composition of his on this recording, called “Sleeping House.” Having just lost Pip [drummer Pip Pyle] made me want to try to do his memory proud in some way. It’s a document and I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone other than a fan. It was a mother to re-master.

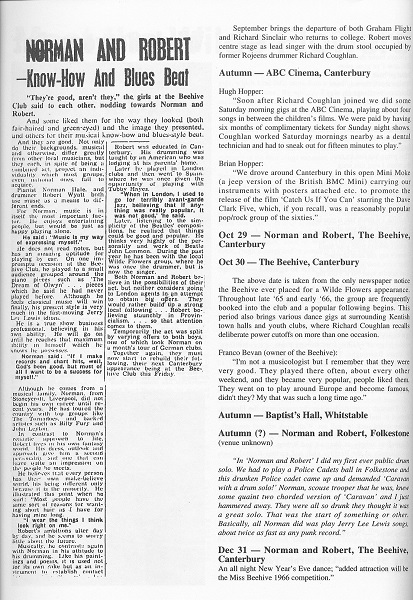

I wanted to ask you about your Mike Osborne recording too. He was pretty much an unknown in America. Tell us why you released that one, and how you found that recording.

I wanted to ask you about your Mike Osborne recording too. He was pretty much an unknown in America. Tell us why you released that one, and how you found that recording.

Mike has always been a favorite of mine. Ever since I heard the early Mike Westbrook records, I sought him out on whatever I could find. He had such a distinctive tone and style, and distinction in jazz, in music period, is a great attractor for me. That recording came from a friend named Andre Henkin, who is one of the editors of All About Jazz, New York. I recognized its importance, because it was one of the last recordings Mike made before illness silenced his horn. This is a man who suffered his demons — serious drug addiction, paranoid schizophrenia and gross alcoholism. I’ve heard some wretched stories about Mike, but I’ve also heard some beautiful stories about him as a person, particularly from his wife Louise Palmer, who blessed this CD release. I just wanted to contribute to his legacy, the recorded work. Since there was nothing after 1977, a six-year gap, I decided to choose this, despite the fact that there are other recordings from the early 70s that are even more remarkable musically. Since the release of Force of Nature, we were granted guardianship of the Mike Osborne tape archive, and I’m really looking forward to assembling a second release. My hope is to place the focus on his compositions, which is something he wasn’t well known for. In fact, he wrote quite a number of compositions. They’re not terribly elaborate, mostly just heads; but there are some rather crafty ones to say the least. There are quite a number of them, and I’d like to have a release that showcases his compositions. There wasn’t much under his own name. It was mostly other people’s records, but there were quite a number of groups that he had that never recorded formally. They are chock-full of passages that are either gorgeous or blindingly brilliant.

You also mentioned you are a huge Jimi Hendrix fan, and that’s what helped indirectly get you into the Canterbury jazz scene.

Yes, kinda, but mostly it was those King Crimson records, because the contribution of the people who played on Lizard and Islands, which are two of my favorite King Crimson records, particularly Islands, because of its sheer beauty. Beauty is one of the principle attributes that I seek in music. It seems to have gone out of favor in the last few decades, at least in the pop realm.

Anyway, when I saw Harry Miller’s name on Mike Osborne’s Border Crossing LP, in a library back in ’77, I picked it up because I recognized Harry from “Formentera Lady.” When I mentioned this to Hazel Miller, she said: “And then the die was cast,” which is true. Then I just continued to do what all of us prog fanatics tend to do, which is to shimmy up the branches and the twigs of all the different kinds of music that we enjoy.

Musicians come and they go, and they take you with them. You go with them wherever they go.

Yeah, that’s right. There was so much cross-fertilization between the rock, folk and jazz worlds in London, particularly in the early 70s. That’s how I discovered British jazz, as a side door from progressive rock. And oddly enough, it was my love of British jazz that led me to check into American jazz, where I discovered Coltrane, Bird, Mingus, and Monk. That put a whole new light on what the Brits were doing over there, to say the very least.

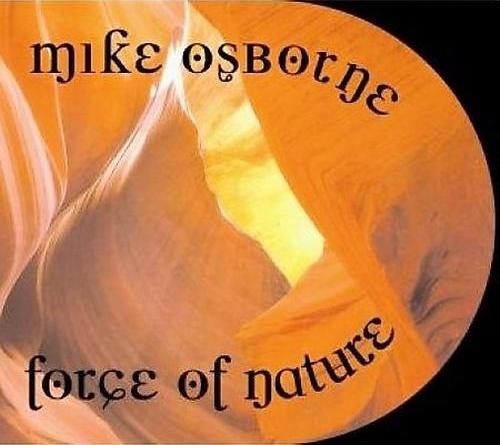

Please tell us about your current project, the Rendell-Carr archive.

Please tell us about your current project, the Rendell-Carr archive.

I learned about this through a telephone conversation with Duncan Henning, who is a reviewer at Jazzwise, who was very supportive of the Mike Osborne CD. Duncan pointed out that there was a nice man named George Foster who had just found his recording of the Don Rendell-Ian Carr Quintet at London University in 1966. George was looking to have it released and Duncan suggested that it might be something of interest for Reel Recordings. So I got in touch with George, who was generous, amiable, and trusting — three of the most important qualities when you are working with somebody. I’ve come to look to work as something that’s only possible when someone wants to work with you. So George sent over a CD-R of the tape, and it was on the second listening that I realized the greatness of this music, but it wasn’t until I got the master reel, which is actually just a small consumer reel, that I realized how good the recording is. It’s not amazing, it’s not a hi-fi recording, but it has a great presence and it’s a very live sounding 60s jazz recording. It will have your foot swinging your toes off and your head exploding with the group arrangements. It’s just a knockout. There’s been a lot of love and support around this as well, because it’s planned to be released in conjunction with the Rendell-Carr performance at Queen Elizabeth Hall on February 23rd.

Is an alumni band being assembled for the concert?

Well, there is an alumni band of sorts as the first act. There will be three acts, if you want to call them that. It starts with Michael Garrick and friends, who will be recreating and performing material from the Rendell-Carr book and some of Michael’s early music. That’s with Dave Green, Trevor Tomkins, Norma Winstone, Henry Lowther, and Art Themen, which is pretty much the original group. The second piece is Ian’s composition “Northumbrian Sketches,” which was composed for strings and trumpet. The trumpeter is Guy Barker and the small orchestra will be conducted by Mike Gibbs. The closing performance of the evening will be “Nucleus Revisited,” with guests Tim Whitehead on sax and guitarist Ray Russell. I think the BBC are going to be recording it, and there’s going to be quite a lot of celebration around this event in terms of media. We’re very excited, as we’re flying over for the concert to meet the musicians and to meet George Foster, finally after all these phone calls. We’ll meet up with old friends and new friends.

And of course no trip to England is complete unless you come home with a pile of tapes. I have been invited to visit Christine Clyne [bassist Jeff Clyne’s widow], and retired bass player Ron Mathewson, who worked with Gordon Beck, Tubby Hayes, Kenny Wheeler, Ray Warleigh, and John Taylor. He said, “Mike, I don’t know what’s here, but I have a big bag of tapes.”

It must be fun to sift through all those tapes.

It must be fun to sift through all those tapes.

Well, you know it is. It’s always an adventure, coordinating and cataloging a tape archive. You run the gamut from blanks to studio masters and all points in between. It’s exciting, particularly when you pick up a tape with nothing written on it, and you say, “What’s this?” because you have no idea. You put it on and the announcer says, “Tonight we’re presenting Joe Harriott Quintet at the BBC Jazz Club.” This is just an unlabeled tape that could have easily been thrown out or been erased over.

It’s akin to archaeology in many ways: first, locating it, and then handling it with care, dusting and preserving, trying to do the best you can. Every tape seems to have its own set of negative and positive attributes. They all need to be analyzed and balanced. That part is one of the reasons why, to my ears, some archival recordings have been mishandled in the re-mastering stage. Few engineers are experienced in dealing with what I’d term compromised recordings. We live now in this digital age, and we have so much computer recording from bands today. What new band produces a sound that sounds like a tape from ’64 or ’74 that has been transferred a few generations and is missing frequencies? Because I have been listening to bootleg recordings and the like for the last 34 years, the equalizer is now a trusted friend, I can approach it knowledge and intuition if you will. It just doesn’t make sense that a young engineer would have this. Many have never heard a pure analog system! What they tend to do is throw on hyper-compression, which is perceived as a panacea for everything; just to make it big, and big equals good. That is not necessarily the case.

As a matter of fact, with this Rendall/Carr recording, I applied some processing in an attempt to compliment the recording, only to find out that the recording sounded the best as it is, with just a few level adjustments and a bass EQ, there it is. Or rather there you are, in the audience (within reason) at this fantastic concert. You have the actual recording that’s as close as you can get to the frequencies of the music performed that night. This is not a conventional approach. Re-mastering engineers like to apply all sorts of tricks to the recording, chalk up a number of hours, and receive a swollen paycheck as the result of it. Sometimes all that is needed is a proper format transfer.

Ideally that would be the best way to approach it, correct?

I know there are a number of companies doing this. With Mike Dutton’s Vocalion label, he is dealing with studio masters of a lot of British jazz records, re-releasing them. And for the most part, they are just straight transfers of the master tapes, which is as it should be. Similarly, with Fledgling Records (UK), their re-masters are wonderful. Someone is really taking good care of this.

You’ve heard Fotheringay 2, correct? That’s a labor of love that went through several salvage operations. Have you heard that?

Yes I have. That’s a nice record. Sandy’s voice is magnificent, as ever.

Have you been in contact with Ogun Records? That catalog is in need of reissue and re-master.

Have you been in contact with Ogun Records? That catalog is in need of reissue and re-master.

We issued Harry Miller’s Isipingo Full Steam Ahead and worked with Hazel Miller on this. It’s a great honor to have been granted permission to have some of Harry’s recordings released outside of what was his label. Hazel is wonderful to work with and that CD is one of my very favorites in our catalog. I would love to do more of Harry’s stuff with the groups he led under his own name. Again, there is a composer who has a number of compositions that had never been published, and they are just absolutely tremendous. Hazel is currently focusing on reissuing the Ogun catalogue and she is not in the position to issue archival recordings from their library. With any luck in the years to come, we will be able to do something else. The problem right now is that our plate is full.

What are you working on next, Mike?

We are doing a recording of Gerry Fitzgerald and Lol Coxhill at the Spectral Arts Center in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1981. It’s a stunning hi-fi recording of two mates in extended improvisational conversation. I just spoke with Gerry yesterday actually. He said, “I used to play guitar and make it sound like three people were playing, but now I am happy if I can make it sound like two people are playing.” He’s 65 and arthritis takes its toll. There was no one else who approached the guitar like Gerry Fitzgerald, save Derek Bailey or Fred Frith, and one of his greatest foils was Coxhill. That’s next and the bonus material will startle.

The other thing we are doing is Nick Evans’ Dreamtime, which is his group with trumpeter Jim Dvorak, Gary Curson (who is a Mike Osbourne protégé), Roberto Bellatalla on bass, and a new stupendous drummer Jim La Baigue. They were really the heirs to the Tippett group and Brotherhood of Breath. It has this amazing, non-threatening energy. The first CD is a recording of them at Bracknell Jazz Festival in 1983, just a quintet off the soundboard with six blinding performances there. The second disc is going to be Double Dreamtime, which is the band augmented by saxophonist Paul Dunmall (Mujician), Paul Rutherford (trombone), Mark Sanders (drums), and Marcio Mattos on bass, and a student of Jim’s, Kevin Davey, on trumpet. The whole band is doubled up. It’s fierce and awe-inspiring, and it needs to be heard. With any luck this CD may open ears to this amazing band.

The hope is just to preserve and share great music with whoever is interested. Too often I have run into musicians who have destroyed their tape archive, thinking that they were valueless musically. The thrill of discovery is like nothing else, but that true for all discovery no matter the medium or discipline.

The hope is just to preserve and share great music with whoever is interested. Too often I have run into musicians who have destroyed their tape archive, thinking that they were valueless musically. The thrill of discovery is like nothing else, but that true for all discovery no matter the medium or discipline.

I long to return to a society where music is actually valued instead of commoditized, not that it wasn’t in prior decades, but today it seems to have been technically compromised to a point near meaninglessness. We have these files on tiny devices that can be erased or shuffled over, like its musical graffiti. As an old fart, I’m from an age where we used to buy a record, sit, listen to it, turn it over, listen to the other side, it was a bit of a ritual. That phenomenon still exists, but it’s minority. As a consequence, recorded music is being under-appreciated. We live in this society that thinks if you can hear music, then it is music. But as anyone can tell you, whether you had a hand-held transistor radio in 1968, or if you have an iPod with $10 earplugs today, just because you hear it doesn’t mean that the integrity of the musical experience is being presented. It’s akin to experiencing a 35mm film print through a convenience store photocopy. Is it closer to truth or travesty? Should we not care?

I have had great fun here getting my 15-year-old stepson into vinyl, and he now rejects his mp3s, except when he’s walking through the streets. Many of his friends want more out of music than what the standard computer download delivers.

Ironically, you can get extremely high-quality sound from the computer as a component, to wit visit computeraudiophile.com, but it takes some care and thought to do this. A lot of ducks must be lined up correctly, contrary to popular opinion. For Reel Recordings this is a labor of love; caring for a recording that is musically moving. I didn’t spent over one hundred hours manually redrawing all the tics and pressing crackle of two Miller / Coxhill records for anything other than the love of the music itself (though admittedly Cuneiform offered respectful compensation). Having said that, I have been greatly touched by all the people associated with it. Whether it is someone who just expresses simple appreciation or a hug from Christine Hopper; I never saw this for myself or for this music 20 years ago, except as a dream, but now with Miki by my side it’s a dream come true.

Filed under: Interviews, Issue 38

Related artist(s): Elton Dean, King Crimson, Soft Machine, Robert Wyatt, Kevin Ayers, Soft Heap / Soft Head, Keith Tippett, Nucleus, Ian Carr, Mike Osborne

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Release: Tashi Wada - What Is Not Strange?

Updated 2026-02-24 14:56:16 - Artist: Tashi Wada

Updated 2026-02-24 14:54:34 - Release: Greg Segal - Maintain!

Updated 2026-02-24 00:38:03 - Review: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Published 2026-02-24 - Review: Nektar - Mission to Mars & Fortyfied

Published 2026-02-23 - Review: Jaime Rosas - Tres Piezas de Rock Progresivo

Published 2026-02-22 - Release: Kevin Kastning & Bruno Råberg - Across Tall Rain

Updated 2026-02-21 00:42:08 - Review: Gary Husband - Postcards from the Past

Published 2026-02-21 - Release: Daniel Crommie - Februa

Updated 2026-02-20 14:23:17