Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

Chasing the Exhilarating Foreboding —

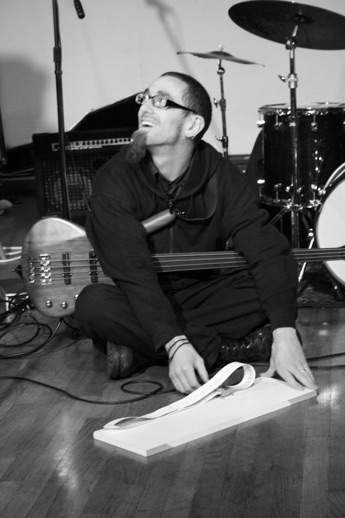

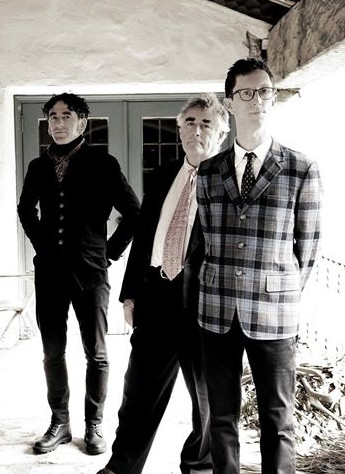

The Jack o' the Clock Interview

For about ten years now, Jack o' the Clock has been turning heads and ears with their singular style of music, which takes in elements of classical music, folk, and rock, combining them with a heavy dose of "It's so crazy it just might work!" Leader Damon Waitkus has assembled an ensemble who demonstrate that formal musical education does not always kill creativity, blending bass guitar and drum kit with violin, bassoon, hammer dulcimer, and countless other instruments common and obscure.

by Jon Davis, Published 2017-05-09

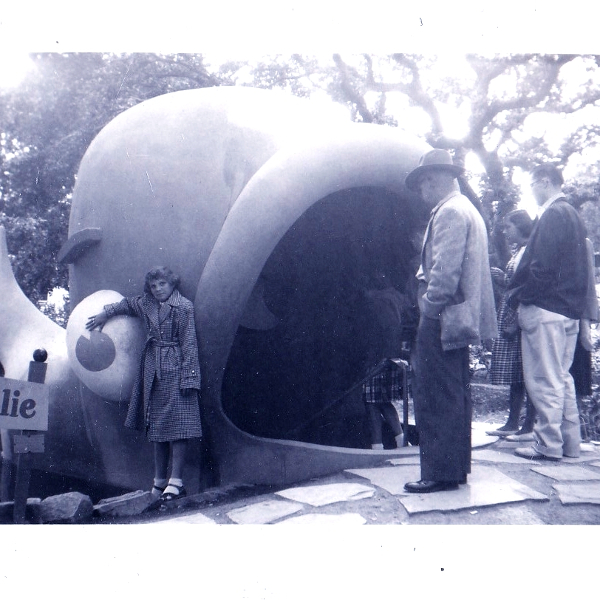

photography by Carly McLane

I connected with two members of the band via email, and they were gracious enough to answer my questions.

- DW: Damon Waitkus — guitar, voice, hammer dulcimer, compositions

- JW: Jason Hoopes — bass, voice, piano

What are your earliest musical memories? How did your conception of music develop?

What are your earliest musical memories? How did your conception of music develop?

DW: I would mess around on my grandmother’s piano any chance I had as a toddler until my mother gave in and brought it over to our house. I remember getting fixated on how C and F sounded together (though I didn’t know the names of the notes), and then resolving the F to an E and feeling there was something pretty amazing going on there. I would also bang on pots and pans if given the chance, which come to think of it is still the case.

My mother played some piano and my father was a decent finger style guitarist. When my mother played the slowly evolving dark green chords of “Moonlight Sonata,” I felt an exhilarating foreboding, like watching thunderheads mounting. And my dad would get the old Martin out — the guitar I had commandeered by the time I was in middle school and still play — and sing 60s folk tunes while I bludgeoned an old out-of-tune zither with a drum stick and sang, "Oooo." I loved the way the metal string sounds blended, in and out of tune, the way the sound filled the room. Nothing’s changed.

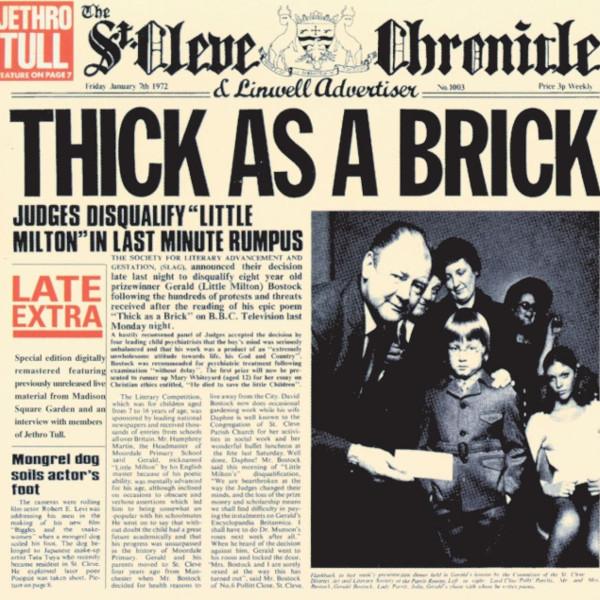

As far as listening is concerned, there were about eight or ten records from my parents’ collection of 60s folk and psychedelic rock that I got to know very well. Most significant among those were Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick and Simon and Garfunkel’s Parseley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme, which I associate with my father and mother respectively. I loved getting lost in TaaB’s continuous, evolving, unbroken landscape — I had an almost synesthetic experience of it as rich colors and complex forms — like exploring a region of woods shot through with sunlight. My dad would turn it up to unneighborly volumes at the “boom boom” end of side one just to make me run screaming around the house, but I always came back for more. Where Tull was thrilling and energizing, I think Simon and Garfunkel drew out subtle feelings of melancholy, love, sensitivity, and a certain silliness, and felt deeply maternal for me. A lot of the guitar sonorities and certainly the subtle vocal harmonies I gravitate towards in my own writing I hear all over that album. And of course acoustic guitar is the grounding element in both those records.

As far as listening is concerned, there were about eight or ten records from my parents’ collection of 60s folk and psychedelic rock that I got to know very well. Most significant among those were Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick and Simon and Garfunkel’s Parseley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme, which I associate with my father and mother respectively. I loved getting lost in TaaB’s continuous, evolving, unbroken landscape — I had an almost synesthetic experience of it as rich colors and complex forms — like exploring a region of woods shot through with sunlight. My dad would turn it up to unneighborly volumes at the “boom boom” end of side one just to make me run screaming around the house, but I always came back for more. Where Tull was thrilling and energizing, I think Simon and Garfunkel drew out subtle feelings of melancholy, love, sensitivity, and a certain silliness, and felt deeply maternal for me. A lot of the guitar sonorities and certainly the subtle vocal harmonies I gravitate towards in my own writing I hear all over that album. And of course acoustic guitar is the grounding element in both those records.

How my conception of music developed from there is a long story, but I can give you a thumbnail. I listened to everything over the years, starting with my parents’ other records, then getting into progressive rock, jazz, celtic music and then contemporary classical stuff — minimalism first, then modernist composers, then feeling my way back into the early 20th-century harmonic explosion — then some African, Balinese, Japanese, Burmese folk musics, and so on.

As far as playing is concerned, I studied piano as a kid, gravitating towards Bach and Debussy, and taught myself guitar as soon as I could get my hands around my dad’s dreadnought. I picked up the hammer dulcimer in 1995 after hearing Malcolm Dalglish, thinking that was one of the most haunting and strangely innocent sounds I’d ever heard, but only started working at my technique around the time I started JotC. I also took some voice lessons and sang in choirs in high school and college.

So I’m kind of omnivorous. Different musics suit different moments in life, different moods, different social and cultural situations. Music is integrated into all parts of my life. Sometimes I want to let it close me into a dark, safe place, and other times I want it to bring me out of myself, to challenge me, show me the world in all its diversity and complexity. Whatever aspect of life, light or dark, needs acknowledgment, deepening and expanding, there’s music for it. This goes for both listening and music-making.

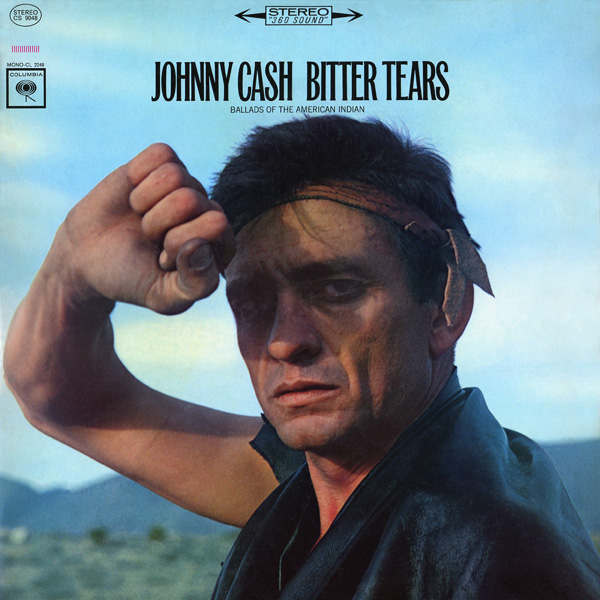

JH: My mom singing and playing guitar, sometimes solo, sometimes with her siblings. Her mother was a big Elvis fan, so that was around. She is a great songwriter, really simple and well balanced folk-style stuff. I remember her playing Fleetwood Mac's Rumours and Creedence Clearwater Revival, and some gospel stuff when I was very young. I remember waking up on Sunday mornings to the smell of breakfast cooking and my dad playing his country records and singing along loudly — Mel Tillis, Jim Reeves, Merle Haggard, Tom T Hall, George Jones, Charley Pride, and others. There are two very important records for me in my earliest memories, one being Johnny Cash's Bitter Tears, which I would listen to laying on the floor, watching dust slowly float on the air in the warm sun rays coming through the window. Haunting background vocals from the Carter Family made a deep impression on me, and Cash's storytelling talk-style of delivering some of the songs also really struck me. There's a real ghostly air that was captured on that record. As an adult, I appreciate that it also dealt pretty acerbically with edgier themes like alcoholism / racism / interracial love affairs ("White Girl"), the celebration of successful violence against the American army ("Custer"), and ongoing genocidal war against America's native population ("Apache Tears").

JH: My mom singing and playing guitar, sometimes solo, sometimes with her siblings. Her mother was a big Elvis fan, so that was around. She is a great songwriter, really simple and well balanced folk-style stuff. I remember her playing Fleetwood Mac's Rumours and Creedence Clearwater Revival, and some gospel stuff when I was very young. I remember waking up on Sunday mornings to the smell of breakfast cooking and my dad playing his country records and singing along loudly — Mel Tillis, Jim Reeves, Merle Haggard, Tom T Hall, George Jones, Charley Pride, and others. There are two very important records for me in my earliest memories, one being Johnny Cash's Bitter Tears, which I would listen to laying on the floor, watching dust slowly float on the air in the warm sun rays coming through the window. Haunting background vocals from the Carter Family made a deep impression on me, and Cash's storytelling talk-style of delivering some of the songs also really struck me. There's a real ghostly air that was captured on that record. As an adult, I appreciate that it also dealt pretty acerbically with edgier themes like alcoholism / racism / interracial love affairs ("White Girl"), the celebration of successful violence against the American army ("Custer"), and ongoing genocidal war against America's native population ("Apache Tears").

The other important record for me from this time is the collection of songs used for the soundtrack for the Buddy Holly biopic Gary Busey starred in. Of course I didn't know at the time, but Busey sang those songs himself for the film, and I am still actually torn between which versions I like best, Buddy's or Gary's! I was mesmerized by that record, listening on headphones over and over, and I played my first musical instrument (drums) along to it frequently. The forceful and primal sexual aggressiveness underneath "Not Fade Away" actually scared me. ("I'm gonna show you how it's gonna be / You're gonna give your love to me"... I am?!) I felt as if I was witness to something truly dangerous and forbidden, and I couldn't look away. I was struck by a kind of perverse obsession with the taboo, a feeling that has never really left me (for better and worse), and played out later in my musical tastes. I also responded to the (arguably) early punk vibe of "Oh Boy!" and "Rave On." Those songs point forward toward Ramones territory, as they also stand on the shoulders of countless black American musicians. From there, the next significant milestone records for me were Michael Jackson's Thriller, Prince's Purple Rain, Beastie Boys License to Ill, various "hair metal" hits, and Tears for Fears' Songs from the Big Chair, which is the first cassette I ever bought with my own money and stands as one of my favorite records by one of my favorite bands ever.

When I was entering my teens, it was an eclectic blend of various popular rap (Run DMC, NWA), thrash metal (Anthrax's State of Euphoria was the gateway), more adventurous "classic" rock like Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin. Most of this stuff eventually lead me to discover more seriously the blues — Robert Johnson, John Lee Hooker, BB King — and the music of black America, which I was not so directly exposed to growing up in rural, predominantly white environments with lingering racist undertones. When I began to play guitar in high school, I was listening almost exclusively to extreme death / thrash metal, classical music, blues, and various new age artists, of which Enya remains the most important to me.

When I was entering my teens, it was an eclectic blend of various popular rap (Run DMC, NWA), thrash metal (Anthrax's State of Euphoria was the gateway), more adventurous "classic" rock like Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin. Most of this stuff eventually lead me to discover more seriously the blues — Robert Johnson, John Lee Hooker, BB King — and the music of black America, which I was not so directly exposed to growing up in rural, predominantly white environments with lingering racist undertones. When I began to play guitar in high school, I was listening almost exclusively to extreme death / thrash metal, classical music, blues, and various new age artists, of which Enya remains the most important to me.

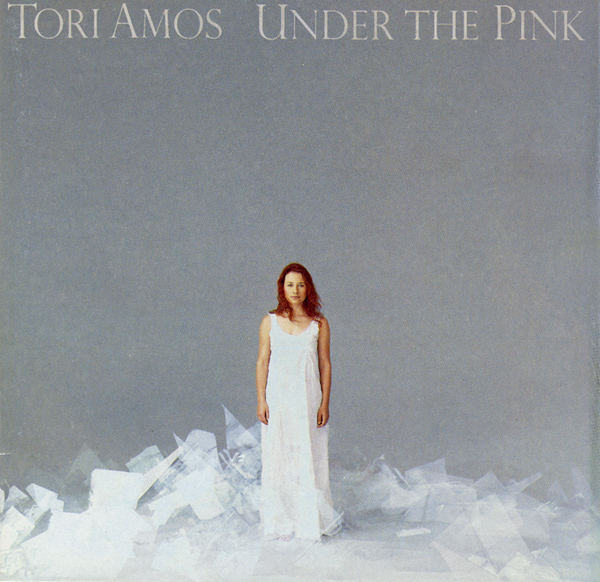

I'm going to leave on Tori Amos' Under the Pink, and Faith No More's The Real Thing and Angel Dust, which all began a whole other big turn for me. From there, of course, the frame broadens dramatically quickly, and it's still going.

What kind of formal schooling do you have in music?

JH: I spent the first six years of my musical life teaching myself to play guitar and bass. In the first two years of playing, I had learned all the rhythm guitar parts and several guitar solos for all of Metallica's records up to the Black Album, along with lots of other stuff, and was bringing my guitar to school to practice, and to parties to entertain (practice). That impressed and inspired a couple brothers (guitarist and drummer) slightly older than me to ask me to join their thrash metal band (the only one in town) as bassist. That was my first band and where I really learned what it means to write original songs and get a band up to a high performance standard (we rehearsed (partied) all the time!). I was 17 years old. We also spent some time as the rhythm section for the local blues band. By the time I knew I wanted to formally study music, I had begun trying to teach myself to read notation, but didn't get very far. There was no music class for me to take in school. What I learned I learned on my own, aurally or through songbooks, or through the few older local musicians I was beginning to associate with — there were only a few, as I grew up in fairly isolated timber industry communities in the mountains of Northern California (4-5 hour drive north of the Bay Area).

JH: I spent the first six years of my musical life teaching myself to play guitar and bass. In the first two years of playing, I had learned all the rhythm guitar parts and several guitar solos for all of Metallica's records up to the Black Album, along with lots of other stuff, and was bringing my guitar to school to practice, and to parties to entertain (practice). That impressed and inspired a couple brothers (guitarist and drummer) slightly older than me to ask me to join their thrash metal band (the only one in town) as bassist. That was my first band and where I really learned what it means to write original songs and get a band up to a high performance standard (we rehearsed (partied) all the time!). I was 17 years old. We also spent some time as the rhythm section for the local blues band. By the time I knew I wanted to formally study music, I had begun trying to teach myself to read notation, but didn't get very far. There was no music class for me to take in school. What I learned I learned on my own, aurally or through songbooks, or through the few older local musicians I was beginning to associate with — there were only a few, as I grew up in fairly isolated timber industry communities in the mountains of Northern California (4-5 hour drive north of the Bay Area).

Once in college, I worked very hard. I would hand-copy scores in the library, and write out harmonies for the figured bass in JS Bach chorales, just to get more inside the music and work on my penmanship and theory. It's taken me quite a while to get over the feeling that I have to catch up! I resented my self-taught beginnings for years, but now I see it as a crucially positive experience. In Humboldt county, I studied with Ed Macan and played bass in his band, Hermetic Science, a name that should sound familiar to some Exposé readers. I have a BS in music from Southern Oregon University, where I played in the jazz big band under percussionist Terry Longshore (a Steven Schick alum), and studied singing with an amazing choral director named Paul French. I applied to Mills and was accepted, where I graduated with an MA in composition and an MFA in performance & literature (improvisation), and where I also first met Fred, Jordan, Emily, and Damon, and then Kate through them as we started meeting to pursue JotC.

DW: I studied composition as an undergrad alongside English and then went on to get an MA in the composition at Mills College a few years later. I started a PhD program in composition at UC Berkeley the following year, but by then I had formed Jack o’ the Clock and realized I wasn’t really interested in pursuing the life of an academic composer, nor did the music there excite me, so I left.

DW: I studied composition as an undergrad alongside English and then went on to get an MA in the composition at Mills College a few years later. I started a PhD program in composition at UC Berkeley the following year, but by then I had formed Jack o’ the Clock and realized I wasn’t really interested in pursuing the life of an academic composer, nor did the music there excite me, so I left.

We all have Masters’ from Mills College actually, except Kate — that’s where we all met. Jordan’s is in performance and literature, with a specialization in improvisation, but he’s also done a lot of composing. He grew up in Eugene playing classical percussion and jazz drums. Emily has an MA in violin performance from SF Conservatory, specializing in contemporary music, as well as from Mills in improvisation. She and Kate both came up through the classical world from an early age, and played in youth orchestras together in Boston. In addition to playing bassoon, Kate has a Masters in conducting from McGill, plays a number of other orchestral instruments, and has a truly encyclopedic knowledge of the classical canon.

What musical activities did you have before Jack o’ the Clock?

DW: I led a band in high school that was similar to JotC in some ways and was really the center of my life for a couple years, even a sort of liferaft. I wanted to go to music school and form another band with better players as soon as I got out, but my parents urged me to go to a liberal arts college (UMass Amherst), which I ended up not regretting, since I did have nonmusical interests. I had a number of musically frustrating years after that in which I was unable to get anything off the ground, probably because of a winning combination of impossibly high standards and low self-confidence, but in the mean time I kept writing and honed the art of 4-track bedroom recording. I was able to bring a few “solo” albums together with the help of a few friends just to get the work out of my system, but always felt I was marking time for another band. By the time I was in my early twenties I was listening to more and more contemporary composers, and gave myself over for a few years to forming a pile of manuscripts. It was a half measure that enabled me to feel like I was completing things so that I could move on, and I learned a lot about orchestration in the process, but ultimately I wasn’t able to fetishize the score, which is a mental contortion I think you have to master to maintain sanity as a composer of reasonably complex music unless you have a devoted ensemble or a degree of commercial success.

I played bass and a little flute in an instrumental band with three other composers right before JotC called Oogog — reeds / bass / piano / guitar — and that was a sort of gateway for me back into a band-oriented mind. We each contributed through-composed pieces, and it varied somewhat but was very minimalist-influenced, sometimes proggy. It was an education for me, having to finally play the ornery, syncopated stuff I was writing as well as what the others were coming up with, and I learned to clarify and distill my ideas and make my notation more humane. And I became a better reader and performer. I was disappointed when that project dissolved, but it was the best thing that could have happened to me musically, since it drove me to form JotC. I’d tasted the band experience again, knew I wasn’t that interested in going back to the abstraction of “pure” composition, and was forced to examine what I really did want from music. Which was something sort of like Oogog, only looser, more collaborative, and decidedly structured around vocals — I wanted to write songs again, but to retain the high performance standard and work ethic that permitted a little complexity from time to time.

JH: I've been in and out of several bands of varying styles of rock, lots of improvisation, various ad hoc ensembles for friends' compositions, lots of experimenting. Groups since coming to Mills include The Atomic Bomb Audition, an early lineup of Annie Lewandowski's Powerdove, and one very intense year (2012) in a bass / drums grind metal duo called Satya Sena, with drummer Peijman Kouretchian, who works with thrash metalers Ghoul and Trey Spruance's Secret Chiefs 3.

How did JotC come together? Was the unusual instrumentation a deliberate choice, or did it just work out that way?

How did JotC come together? Was the unusual instrumentation a deliberate choice, or did it just work out that way?

DW: A bit of both. I started it with Emily and Nicci Reisnour, a fellow composition student at Mills who left after a year to study Gamelan in Bali — she played harp, wine glasses and melodica, which blended very nicely with my guitar and dulcimer and Emily’s violins and psaltery. I was excited to be singing and writing songs again, and didn’t have ambitions to form a rock band right off the bat. I was trying to be practical, hone my craft and develop my voice, start performing and recording, and let the specifics of the live ensemble follow — I’d spent too many years in my head and was wary of letting any ideas develop that depended on instruments we didn’t already have in the band. Our initial tunes were thus relatively simple folk numbers which are scattered across the first few albums — “All Last Night,” “Ultima Thule,” “Disaster / Analemma” “New American Gothic,” “Last of the Blue Bloods.”

The trio, which soon became a quartet when Jordan joined after six months or so (he didn’t bring his his drum set at first because the band was so quiet, playing instead an array of metals on the floor) was high-end heavy, and we thought bassoon would be a unique timbre to handle the low-end if we could find a bassoonist. Then Emily ran into Kate by chance, whom she’d known from youth orchestra as a kid on the East Coast, and Kate could also sing and play flute, and she was interested in checking us out. And simultaneously Jason responded excitedly to something we posted online, and we knew him to be a fantastic bass player who already had a synergistic relationship with Jordan, so we asked him to join too. Nicci left and then Kate and Jason showed up, it was all like the same week. And of course, with a full-fledged bass player unexpectedly on board, it made sense for Jordan to move over to drum set and for the rest of us to start using amplification. Though it hadn’t been my plan, I couldn’t have been happier about going in that direction.

Given that there’s an obvious connection between JotC music and folk music, have you gotten any reactions from the folk community?

Given that there’s an obvious connection between JotC music and folk music, have you gotten any reactions from the folk community?

DW: Not that I know of. We certainly played a lot of shows with other “folk” acts, and in the earliest days of the band, when I heard people like M. Ward, Joanna Newsom, and Sufjan Stevens doing some creative and ambitious things with songwriting and production within the loosely-defined “folk” world and having major success, I thought it was as good an angle as any to pursue, promotion-wise. At the end of the day, I don’t feel we’re any more “folk” than “prog,” but the latter community is the one that has opened up to us, so I’ve tailed off on pursuing the “folk” pitch so much.

Emily and I have had some friends like the people in the truly magical band Chimney Choir who have done their time in an actual American folk circuit, touring the South and playing bluegrass gigs in restaurants and whatnot to pay the bills in between shows of original material, which are blazingly inventive and beautiful theatrical performances that just happened to be rooted in a well-defined and virtuosic folk tradition. The Punch Brothers would be another example of creative music-making with identifiable folk roots. Chris Thile has said that great music has more in common with other great music than with the music that shares its genre, which is ultimately a bunch of surface elements, and I buy that completely. It’s splitting hairs what you call it when something is inspired.

How do JotC pieces come about? Are they completely composed and presented to the group, or is there collaboration?

DW: We have used every method available to us to create music short of throwing the I-Ching, though chance too always ends up elbowing its way in a little before a piece is done. Some of it is quite composed-out (though rarely a complete piece), and some of it is put together more like a traditional singer-songwriter would, with me coming in with changes and a melody and the others filling in their own parts. Oftentimes I’ll have an incomplete piece and someone else will have ideas that spark the next section — these might be fully composed-out ideas themselves or just lines someone has on their instrument that I write new parts over. A lot of back and forth. The lyrics usually end up dictating the form of the song in the end — what is needed in terms of mood-arc and pacing. So to that extent I tend to steer the ship. But there is input from everyone.

And then there are some record-only pieces (like much of what is on our next-to-last album Night Loops) which are built up from extensive overdubs, composed partially on paper, partially “to tape.” I like doing this because it produces results we just wouldn’t get in the rehearsal room, not only because I can have, say, eight bassoons, but because there is a spontaneity to the parts — sometimes you’re hearing the first time someone played something, it’s very fresh, there isn’t a lot of mental mediation. At the same time, these pieces also take a lot more work to record because the orchestration problems haven’t been worked out in the rehearsal room. But that is also what makes them idiosyncratic. Several times we’ve gone back and learned “studio” pieces to perform after the fact and they always have a different feel from the stuff we rehearse a lot before recording. “The Pilot,” from our album All My Friends is a recent example, we literally just started playing that live.

And then there are some record-only pieces (like much of what is on our next-to-last album Night Loops) which are built up from extensive overdubs, composed partially on paper, partially “to tape.” I like doing this because it produces results we just wouldn’t get in the rehearsal room, not only because I can have, say, eight bassoons, but because there is a spontaneity to the parts — sometimes you’re hearing the first time someone played something, it’s very fresh, there isn’t a lot of mental mediation. At the same time, these pieces also take a lot more work to record because the orchestration problems haven’t been worked out in the rehearsal room. But that is also what makes them idiosyncratic. Several times we’ve gone back and learned “studio” pieces to perform after the fact and they always have a different feel from the stuff we rehearse a lot before recording. “The Pilot,” from our album All My Friends is a recent example, we literally just started playing that live.

As a composer, where did you get your inspiration initially? Where do you see yourself fitting into the history of music composition? (I’m thinking conceptually rather than any sort of quality comparison. For instance, what composers have influenced you?)

DW: Well, I already blabbed about my early influences. When I first started doing honest-to-god composing after college — putting notes on paper — I was most inspired by Charles Ives, Gyorgy Ligeti, Morton Feldman, Lee Hyla, Frank Zappa, and also some older composers like Bartók, Shostakovich, Stravinsky. But that was a different time too. The most exciting music for me recently has been Esperanza Spalding, Faun Fables, Zammuto, the Punch Brothers, Anohni.

Fred Frith is in a category of his own for me, not just musically and because he’s been a mentor, but because he flows freely between the free improvisation, rock, contemporary classical, and jazz worlds, and doesn’t seem overly concerned with how he fits in. Because of the connection with him and his history with Henry Cow, many have slotted us into the RIO category (even though that genre seems to have a sound that’s very different from ours), so on the off chance we end up inscribed into any histories, it’ll probably be the ones that acknowledge that lineage, whatever it is. There are a lot of contemporary musicians — well, it’s been going on at least since the 80s — particularly in New York and the Bay Area, who write and play in the interstices and let others worry about what to do with them.

Fred Frith is in a category of his own for me, not just musically and because he’s been a mentor, but because he flows freely between the free improvisation, rock, contemporary classical, and jazz worlds, and doesn’t seem overly concerned with how he fits in. Because of the connection with him and his history with Henry Cow, many have slotted us into the RIO category (even though that genre seems to have a sound that’s very different from ours), so on the off chance we end up inscribed into any histories, it’ll probably be the ones that acknowledge that lineage, whatever it is. There are a lot of contemporary musicians — well, it’s been going on at least since the 80s — particularly in New York and the Bay Area, who write and play in the interstices and let others worry about what to do with them.

I still do draw inspiration from the aforementioned Serious Music of the White Man, but I’ve also recently started hearing it in a new way. I was listening to some Spectralist music recently, which I remember having responded to about ten years ago and was curious to hear again, and found the music cold and alienating. I think I did back then too, but I also felt that it was my duty to learn from it, to get inside and endure its headspace so that I could, I don’t know, grow into it or something. What’s changed is that I don’t have the sense of duty anymore, and for the first time I didn’t take my negative experience of the music entirely upon myself, blaming it on my personal associations and inadequacies. Personal associations matter, to be sure, but the composer brings something to the music as well and can answer to it. I’ve always responded to alienation in Western music, but only recently started to hear how culture-bound it is — that is, chosen. It’s a tragic cry filtered through the brain, beautiful at times, but I realized I didn’t have to climb up into the belfry so that I could feel a particular brand of loneliness and be compelled to make a particular sort of cry. I could cry more immediately if I wanted to, even with unalloyed joy from time to time.

The Outsider Songs album provides a fascinating glimpse into the influences of the band, some of which are quite unexpected. How were these songs chosen, and were there some others that you wanted to do but couldn’t include for one reason or another?

The Outsider Songs album provides a fascinating glimpse into the influences of the band, some of which are quite unexpected. How were these songs chosen, and were there some others that you wanted to do but couldn’t include for one reason or another?

DW: It’s a semi-arbitrary cross section of mostly high-school era influences — you know, the period they say you never get over completely. Jason chose and co-produced “The Chauffeur” (my personal favorite), Emily pushed for the Paul Simon and the Björk (which we’d actually played live once or twice in the distant past), and I chose the rest, cuz, you know, Democracy.

You’re not the first to say that that some of the choices were surprising, and it always begs the question in my mind as to what would have been expected! In general, what is fun for me in this context is taking a relatively simple song and messing with it. If the song is complex to begin with it is a lot more work and there is less room for creativity. I guess the beautifully simple reductionist cover is a thing too, but that wasn’t what I felt like doing this time around. In the more conservative covers (“Mute Witness” and “Wrong Child”) it was simply a matter of wanting to hear these songs arranged with a hammer dulcimer at the center of the band instead of guitars or piano. In the others it was a more radical re-composing down to structural elements of the songs.

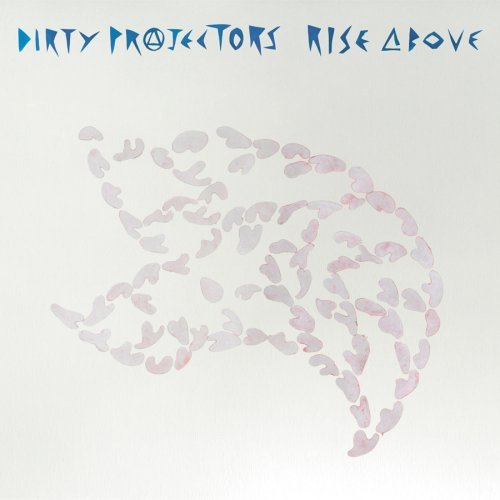

Two precedents influenced my approach to the covers: Dirty Projectors’ Rise Above album and Yes’ early covers, particularly of Paul Simon’s “America.” In both cases, the songs undergo radical transformations—not just the orchestration but the rhythms, tempi, even the chord changes and melody in places. I’d known “America” from early childhood and was pretty amazed when I got into Yes in middle school and discovered what they’d done to it. “Rise Above” is not just a song of course but a whole Black Flag album Dave Longsreth reproduced from memory. But if you listen to that album it is so much more Dirty Projectors than Black Flag. If memory fails, well, you fill in the gaps as you would want them filled in rather than waste time picking apart the original. It is about deepening the spirit that moved in the original, not replicating the details.

Two precedents influenced my approach to the covers: Dirty Projectors’ Rise Above album and Yes’ early covers, particularly of Paul Simon’s “America.” In both cases, the songs undergo radical transformations—not just the orchestration but the rhythms, tempi, even the chord changes and melody in places. I’d known “America” from early childhood and was pretty amazed when I got into Yes in middle school and discovered what they’d done to it. “Rise Above” is not just a song of course but a whole Black Flag album Dave Longsreth reproduced from memory. But if you listen to that album it is so much more Dirty Projectors than Black Flag. If memory fails, well, you fill in the gaps as you would want them filled in rather than waste time picking apart the original. It is about deepening the spirit that moved in the original, not replicating the details.

Kate Bush and David Bowie are two other old and significant influences of mine each of whom have had many songs I can imagine taking a stab at. “And Dream of Sheep” was on the table for a while. The biggest dissuading factor for me was that their voices and arrangements have such strong flavors already that I was afraid I’d only end up watering them down. Björk is of course inimitable too, but there was something irresistible about the challenge of taking on "Hyper-ballad" anyway… tastelessly progging the hell out of the middle of it…

Does the band play live very often? Local shows, festivals, and so on.

Does the band play live very often? Local shows, festivals, and so on.

DW: We’re very much looking forward to getting the old quintet back together (with Kate McLoughlin) to do a little Northwestern tour in early June, culminating in Seattle’s Seaprog festival.

In general, we play a handful of local shows a year, not quite as many as we used to. We’ve become a little more selective with venues because our monitoring and sound needs are more complex than the average band and we got tired of putting over a compromised sound, not being able to hear ourselves, etc. We sound better in slightly bigger venues, festivals and whatnot, which narrows the choices considerably. It’s always a balancing act between wanting to have shows to play at all and wanting to sound good.

What are the band’s future plans? Is there a Repetitions of the Old City - II in the works?

DW: I’m working on Repetitions II right now, building upon basic tracks taken from the same sessions as Repetitions I. Much of this material is both older and darker than what went onto the first one — there are a couple of lines and chord changes which even go back two decades — which leads me to want to produce it a bit more: the farther removed I am from the inception of a piece, the more I want to bring my present consciousness into it on the production end. It feels different from the first one to work on. I’m always most excited by what I’m working on right now, and that’s true here, but because the content digs deeper into my own psychological history — and not always the parts of it I want to dwell on — I sometimes feel stretched and distorted when I come away from a session, or like I’ve just crawled out of a cave. Some of these songs were tools for me in the process of digesting my teens and early adulthood, during which time I was coming to terms with mental health and alcoholism issues in my family, and at the same time becoming aware of the shadow side of American history, higher education, the social milieu. It’s a process of integration.

DW: I’m working on Repetitions II right now, building upon basic tracks taken from the same sessions as Repetitions I. Much of this material is both older and darker than what went onto the first one — there are a couple of lines and chord changes which even go back two decades — which leads me to want to produce it a bit more: the farther removed I am from the inception of a piece, the more I want to bring my present consciousness into it on the production end. It feels different from the first one to work on. I’m always most excited by what I’m working on right now, and that’s true here, but because the content digs deeper into my own psychological history — and not always the parts of it I want to dwell on — I sometimes feel stretched and distorted when I come away from a session, or like I’ve just crawled out of a cave. Some of these songs were tools for me in the process of digesting my teens and early adulthood, during which time I was coming to terms with mental health and alcoholism issues in my family, and at the same time becoming aware of the shadow side of American history, higher education, the social milieu. It’s a process of integration.

Kate leaving has forced us to make some musical adjustments. We just did a couple shows with a new sextet including Thea Kelley on vocals and our longtime collaborator Ivor Holloway on reeds. It’s been invigorating, though unfortunately we’re losing Ivor soon too. Thea and Ivor have been contributing significantly to Repetitions II, so we’ll be a septet on this album.

There will be some changes after this, hard to say in what direction. There’s so much going on in the world and our lives right now, and the present moment is asserting itself. Shifting thematic preoccupations. After Repetitions II is done, I think I’m going to take a personal hiatus from recording and focus on developing a bunch of new material for the live band — really looking forward to doing that, actually — and I’ll feel out where we’re going then.

What are some of your musical activities outside JotC? How about the other band members?

JH: Most recently I had a dark pop trio called Perfect Loss (disbanded) that I played bass and sang for. I am beginning to work with a local guitarist, who works with The Residents, on material for his metal band (Dimesland) to record for his next record. Jordan and I perform all the time together in various projects, but particularly with Fred (Fred Frith Trio). We just completed our second tour of Europe, and have a record out on Intakt called Another Day in Fucking Paradise. I've recently been playing locally with Scott Amendola and Karl Evangelista, and we're discussing the future. Other than those projects, there is a steady stream of work flowing around from various band leaders and composers. There's more music to play than time to play it in! We are blessed! I also teach high school full time (which I absolutely love), so that's how I spend many of my daylight hours.

JH: Most recently I had a dark pop trio called Perfect Loss (disbanded) that I played bass and sang for. I am beginning to work with a local guitarist, who works with The Residents, on material for his metal band (Dimesland) to record for his next record. Jordan and I perform all the time together in various projects, but particularly with Fred (Fred Frith Trio). We just completed our second tour of Europe, and have a record out on Intakt called Another Day in Fucking Paradise. I've recently been playing locally with Scott Amendola and Karl Evangelista, and we're discussing the future. Other than those projects, there is a steady stream of work flowing around from various band leaders and composers. There's more music to play than time to play it in! We are blessed! I also teach high school full time (which I absolutely love), so that's how I spend many of my daylight hours.

DW: I’m extremely busy with family, school, and teaching, so there is not much room in my life for music other than Jack o’ the Clock, which will take as much of my time as I let it. That said, I’ve played electric guitar a few times recently with Moe! Staiano’s Guitar Ensemble, which may also be recording shortly, and once in a while will write a piece for an outside ensemble if asked.

I wrote a duo for electric guitar and drum-set a few years ago at the behest of the phenomenal Living Earth Show, and co-produced our recording of it — hopefully that will be released shortly. It’s the heaviest music I’ve ever written, and I really want to get it out there, but it’s out of my hands.

I’ve also contributed singing and various instruments to recent recordings by songwriters Art Elliot, Eli Wise, and Nathan James. And I played dulcimer in Jordan’s Mindless Thing project and banjo in his Weiner Kids’ family band, though neither are active at present. So yeah, as I was saying, all Jack o’ the Clock…

How does a band like Jack o’ the Clock survive in today’s music world? How do you deal with the business as opposed to the creative aspect of making music?

How does a band like Jack o’ the Clock survive in today’s music world? How do you deal with the business as opposed to the creative aspect of making music?

JH: I'm not sure what "survive" means. None of us are living off the band. If you mean to ask how we keep from developing a cynical attitude or lose faith, I think it comes down to the personal chemistry. We share a great love and respect for each other. The musicianship is strong and inspiring, we keep each other on our toes. And an adventurous attitude, a kind of "let's see what happens" approach. We've learned some things, the business side has its own curve. Damon can elaborate more clearly, but I think it's fair to say we've always poured the bulk of our energy into developing the music and refining the sound, kind of at the expense of developing sharper business practices sooner. But I suspect I won't be regretting that on my death bed.

DW: I better talk second so we don’t end the interview with the words “death bed.” Everything Jason said I agree with. I deal with the business as much as I need to to feel that the band really “exists,” is more than a bedroom project, but I draw that line according to the whim of the day.

Charles Ives is one of my compositional heroes, and I’m all too aware of the arc of his creative life: he worked really hard building up a style and an oeuvre in his early years, then burnt out creatively and devoted his later decades entirely to getting his existing music out. Well, I don’t want to do that! I want be able to stay creative, stay actively making new art as long as I can, it’s too intermingled with my personal growth itself for me to feel like I can healthily stop it. Which means on some level that I have to make sure the work I’m doing now gets heard, at least a little. It’s not for me that I do music, it’s actually an elaborate way of being social, since I’m very introverted on a day-to-day basis. I want people to hear it, and I want them to want to hear it. The market is ugly and petty, but at least I know that the people who find us there aren’t interested in it for some other reason.

Filed under: Interviews

Related artist(s): Fred Frith, Jack o' the Clock

More info

http://jackotheclock.com

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Release: Tashi Wada - What Is Not Strange?

Updated 2026-02-24 14:56:16 - Artist: Tashi Wada

Updated 2026-02-24 14:54:34 - Release: Greg Segal - Maintain!

Updated 2026-02-24 00:38:03 - Review: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Published 2026-02-24 - Review: Nektar - Mission to Mars & Fortyfied

Published 2026-02-23 - Review: Jaime Rosas - Tres Piezas de Rock Progresivo

Published 2026-02-22 - Release: Kevin Kastning & Bruno Råberg - Across Tall Rain

Updated 2026-02-21 00:42:08 - Review: Gary Husband - Postcards from the Past

Published 2026-02-21 - Release: Daniel Crommie - Februa

Updated 2026-02-20 14:23:17 - Artist: Daniel Crommie

Updated 2026-02-20 14:22:43 - Release: b.mez - Under Circuitous Skies

Updated 2026-02-20 14:18:27 - Artist: b.mez

Updated 2026-02-20 14:17:34 - Release: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Updated 2026-02-20 11:36:17 - Review: Maledictis - Echoes of Conscience

Published 2026-02-20 - Release: Lorenzo Montanà - Velan

Updated 2026-02-19 23:52:26