Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

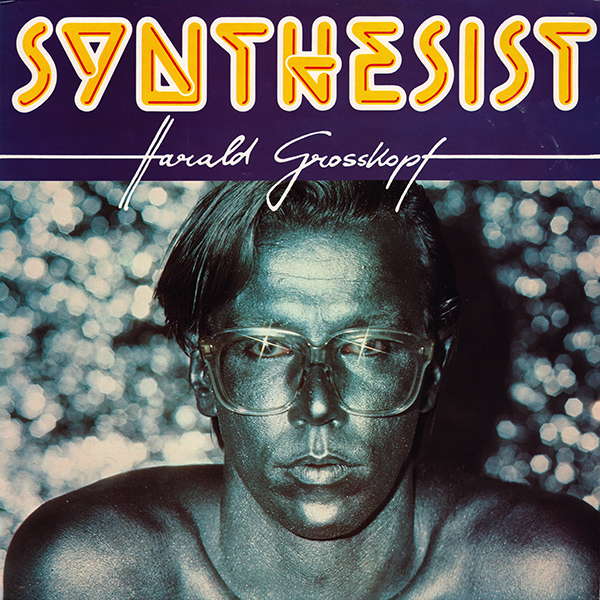

Human Drumming & Machine Beats —

The Harald Grosskopf Interview

Harald Grosskopf has a long musical career starting as the drummer with Wallenstein in the early 70s and eventually venturing into electronic music via The Cosmic Jokers/Cosmic Couriers, Ash Ra, Klaus Schulze, his solo work, and most recently Sunya Beat.

by Henry Schneider, Published 2014-01-06

photography by Henry Schneider

Through my friendship with Uwe Cremer (Level ∏), I was able to meet Harald on a warm summer morning this past July in Köln, Germany. The weather was perfect for an al fresco breakfast and conversation at the Café Lichtenberg on Richmondstrasse in Neumarkt. Joining us were Uwe and my son. Harald is extremely friendly and personable and time just flew by. We were only going to meet for an hour as Harald was leaving for Sao Paolo in two days, but our visit lasted two hours. Here are some excerpts from that July morning that provide an interesting insight into one of Krautrock’s legends.

Through my friendship with Uwe Cremer (Level ∏), I was able to meet Harald on a warm summer morning this past July in Köln, Germany. The weather was perfect for an al fresco breakfast and conversation at the Café Lichtenberg on Richmondstrasse in Neumarkt. Joining us were Uwe and my son. Harald is extremely friendly and personable and time just flew by. We were only going to meet for an hour as Harald was leaving for Sao Paolo in two days, but our visit lasted two hours. Here are some excerpts from that July morning that provide an interesting insight into one of Krautrock’s legends.

I was curious about your upcoming trip to Sao Paolo and the Oscillations Festival. I was trying to find out more online, but there is not a lot of information at all.

Because it is a new festival and it is the first time that Fabricio Cavalho has organized it. The festival is quite small compared to the size of Sao Paolo with its 21 million inhabitants.

There are just four guests: one of the members from Silver Apples, you, Roedelius, and Herbert Deutsch (co-inventor of the Moog synthesizer).

There are just four guests: one of the members from Silver Apples, you, Roedelius, and Herbert Deutsch (co-inventor of the Moog synthesizer).

Yes, Fabricio hopes to grow the festival in the future. But it is a great idea and they pay better than New York did.

Is that right? [Laughs] Well that is good that they have the money. That is interesting because in Japan there is also a big interest in Krautrock.

That’s right. Japan is awesome! I really love it. It is SO different. It blows your head. Because of these colorful hieroglyphs all around…. Such a different language and unpredictable behavior. It is almost magic. And they don’t have any limits in the case of using electronics. Like the Q-code writer-reader you have on your phone. You put your phone on a tombstone and the phone opens up photos of the one that had passed away and plays mourning music. There is a science fiction atmosphere in towns and in the countryside, an Asian middle age sort of thing. I bought a Chinese smart phone you know. It is pretty bad. When the screen flips over when turning the phone it never flips back. I don’t know why. The touch screen also doesn’t work well. Japanese products are perfect. I remember times when Japanese products had very bad quality and a cheap image.

I see that they will be showing the BBC film about Krautrock at the festival.

I see that they will be showing the BBC film about Krautrock at the festival.

They show the film and after the screening Joachim Rodelius and I are supposed to talk about Krautrock in general and our personal development in making music. The thing is that we don’t feel like Krautrockers for some reason, at some point in the past electronic music was mixed into Krautrock. Krautrock was a swear word, created by the British music press in the 70s, because of this incredible nice nutritional food called sauerkraut Germans have eaten for centuries. It is very tasty. It saved millions of people’s lives on sailing ships during their long oversea trips, because it contains a lot of vitamin C. Sauerkraut is well preserved and lasts for months. Now Krautrock is a worldwide known honorable cultural term. I don`t mind to be mixed into it.

For this lecture you are to give, have you planned it out? Or are you just going to talk?

Not yet, maybe on the airplane. I like free speech anyway, much better than preparing too many words. And I’ve taught it so many times already that it is easy.

It works better when you can kind of just talk and you’re comfortable with the material.

And the music is ready you know. And the thing is, I’m no keyboarder. Fabricio wanted me to play some analog stuff on stage after the lecture with some analog synthi-keyboards. I’m a drummer first and I do not feel not very comfortable playing keyboards. Because I work in a much different way, constructing my music by using sequencers, arpeggiators, and MIDI. That way I can repair it afterwards. I will present in Brazil the way I compose, the actual way using a notebook and VST synthesizers. Anyway, I was never really a fan or adorer of analog synthesizer stuff. Of course it is an incredible sound, but in these days you know the virtual instruments are so close to that analog reality so you don’t need such heavy oversized retro stuff. I am travelling with a MacBook. My whole studio is in there. My bureau is in there. My film archive and my photo archive are in there. It is great! All I need is a little USB-keyboard and a small mixing desk and I`m fine.

Do you remember the first time that you ever heard a synthesizer?

Do you remember the first time that you ever heard a synthesizer?

Yes, the first synthesizer we used on Wallenstein, I think it was a Korg with all those presets and stuff. The sounds were similar to natural instruments. But the second time it was in a studio, there was this MiniMoog. I was trying to get a sound out of it, it didn’t work. Usually you turn knobs from left to right to turn something up. I did that with the envelope generators attack knob. So the Moog was silent and I had no idea until somebody said that I should turn that knob to the left. And magic! I was really thrilled the first time I heard a sequencer. It was in Klaus Schulze’s cellar. He switched the thing on and it started grooving from the first moment. I was fascinated by this groove. Because I was visiting Klaus I had no drums. I looked around, discovered a plastic box in a corner, and started drumming on that thing. Klaus was fascinated and a few weeks later we produced Moondawn. That box thing was the initial work with him.

You and Klaus are both percussionists. And your style is so different from all the other synthesists.

Thank you, Henry! In those days you had to explain what a sequencer was. Most musicians around me wouldn’t know what that was. After you explained that it is a machine, they complained that it is artificial, dead, and inanimate. But I was fascinated. For some reason I wasn’t scared to accompany a sequencer or a metronome, like some other musicians did. When I hear click, click, click, my whole physical constitution is tuned in. The art is, not playing exactly in time. A groove is always like this. It’s part of the secret between the magic of human drumming and machine beats.

I’ve noticed this recently because I’ve selected some music to run to on the treadmill, 155 BPM or 160 BPM, and all of a sudden you feel like you’ve lost your place. That just throws you off when you are trying to run on the beat.

Just half time it in your mind and you can relax again.

I thought that it would be good to try Neu! and Klaus Dinger’s motorik beats, but even that is moving all over the place.

Klaus Dinger was a great and emphatic drummer. May he rest in peace. Talking about groove and magic, it is strange you know, fans of electronic music, conservative fans, they don’t like techno. They say it is too regular and too much bass drum, which is not true. If you open yourself up to techno music, you’ll be fascinated by its magic and simplicity. Of course, like in all music, there is trash and some very good stuff. Techno it is a unique style like blues, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, etc. Especially for hardcore EM fans, they should carefully listen to what I’ve done on all of my records to find that I kicked the bass drum, most times in that same straight quarter notes beat.

So the Synthesist album, was that all sequencers?

So the Synthesist album, was that all sequencers?

Sequencers, handmade solos, and real drums. It was very complicated because MIDI was not invented in 1979. I wanted a second, a third, and sometimes a fourth sequence, parallel running to the first one. First of all I had to kind of format one track of my eight-track recorder. Fortunately there was one guy living in the house where I recorded Synthesist, an electronics freak. He soldered a cable with some electronic device in it that was able to create, from the gate output, an analog pulse, that could be recorded and which vice versa triggered my second and my third sequencer parallel in time. The most horrible thing was that the tuning of these very first MiniMoogs was not stable. Not only up and down, you also had to adjust the octave spread. Adjusting that was always a pain. There were a few little holes in the Moog rear and you needed a small screwdriver for up and down tuning and octave spreading. Tuning never ever kept the stability for more than one hour. I made harmony changes by pressing one key accidentally at one point. To be able to catch this point when I overdubbed another sequence I used a microphone to record my voice on one of the tracks saying for example: “F 2 3 4, 2 2 3 4.” Two bars to be able to get the right harmony change for that other sequence. Anyway after recording 10 minutes and beginning a second sequence, I heard, after three or four minutes that the tuning was terribly off. This happened hundreds of times during the whole session. It sometimes took 15 to 20 recordings to get it in tune!

I have always been fascinated with Klaus Schulze and his massive 20 - 30 minute pieces. Did he record them all at once? Or, did he record a bit and then come back to it later?

To tell you the truth, it was horrible sometimes when he played live. He had a pretty bad sound. It had to do with the tuning instability of his Moog. If someone opened a door backstage, the temperature went down for a few degrees and all those six oscillators differently changed the tuning. Cacophony you know! In the studio the tuning was a ritual for hours. I always wondered why people liked that performed live, because it was always so nice and different in the studio.

My impression is that most of Klaus’ work was improvisation.

Yup. Where do you live?

In Austin, Texas.

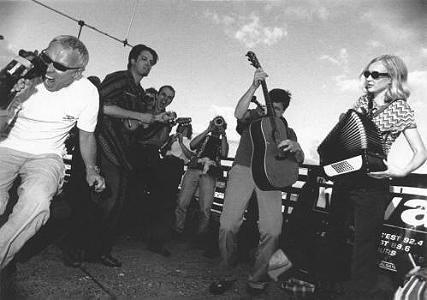

Hey, I was there in 1999 for the South By Southwest (SXSW) Festival. Yeah, it was with the 17 Hippies, a Berlin folk band. We traveled with thirty people. It was a great experience. We slept in private accommodations, spread all over town. And I listened to other bands. Don Walser, a bluegrass hero, was cool. He was so incredibly heavy that he had to be propped up on a wheel chair to be able to get on stage. He had such a clear voice and was supported by brilliant musicians. When he found out that a couple of Germans where among the audience he started yodeling for us. That was first time in my life that I enjoyed bluegrass music!

Hey, I was there in 1999 for the South By Southwest (SXSW) Festival. Yeah, it was with the 17 Hippies, a Berlin folk band. We traveled with thirty people. It was a great experience. We slept in private accommodations, spread all over town. And I listened to other bands. Don Walser, a bluegrass hero, was cool. He was so incredibly heavy that he had to be propped up on a wheel chair to be able to get on stage. He had such a clear voice and was supported by brilliant musicians. When he found out that a couple of Germans where among the audience he started yodeling for us. That was first time in my life that I enjoyed bluegrass music!

You have quite a long musical career. What are most your favorite memories?

My most favorite memory is when I first put my feet into a professional recording studio. It was thrilling and frightening by the same time. What would be in the end? Would I fail or triumph? Another good memory is the four weeks of the Ashra France / Switzerland tour in late autumn 1977. The weather was still great in France, much warmer than usual in Germany at the time. In Aix En Provence, a beautiful town in South France we had breakfast outside the restaurant. We were a great team and had a lot of laughs, no matter if we had good or not so good gigs.

Do you prefer performing solo or working in a band?

I really can’t say. My tendency is to work alone. I had good and bad experiences in both situations. Working with more than three band members is stressful for me. Today I prefer working with small two person teams.

Please tell me about the documentary German Sons, how you came to be involved in the project, and how that has affected your life.

Please tell me about the documentary German Sons, how you came to be involved in the project, and how that has affected your life.

Until I met Hollywood director Philippe Mora (who had Jewish German, French, Australian roots) in Berlin on the ninth of November, 2009 (20th anniversary day of Germany’s reunification), I did not have much contact with people with Jewish roots. My father was a Nazi Party member and helped the ambushing of Poland and Czechoslovakia as a Wehrmacht soldier in 1939. I never heard any words of regret or sympathy for the victims of the Third Reich from his mouth, nor from any other members of that generation. Being German was an emotional burden for me until I discovered at age twelve what Germany had caused to happen between 1933 and 1945 to the world, Jews, and other victims. The German society favored having amnesia until 1968, when students all over Germany started rioting and asking questions. The administration, police, jurisprudence, universities, and my teachers were full of Nazis. Every eighth Member of Parliament was a former Nazi. I was full of shame and felt guilty for the Nazi crimes, even though I was born four years after World War II. Philippe and I became friends that night in Berlin. After that, we had deep personal talks about our fathers and we decided to produce a documentary film about our dads. His father, a German Jew and communist, fled from Leipzig, Germany in 1933, after Friedrich-Wilhelm University Berlin (now Humbold University) kicked him out of medical school when they discovered he was Jewish, which he had withheld for good reasons. Günther Morawski, Philippe’s father, became a member of the French resistance and changed his name to George Morand and fought the Nazi Wehrmacht in France, Spain, and North Africa. Later, he immigrated to Australia and changed his name to Georges Mora. Speaking in public about my neurotic feelings and my lifelong dispute with my father was a great psychological liberation of that burden.

How did your childhood and that legacy affect your music?

I guess the rebellion against that Nazi generation was the main part of my decision to become a musician and definitely influenced my style.

You co-wrote, co-produced, and provided the soundtrack for the movie. Was this music composed specifically for the movie? Or did you use music you previously released?

Part of the music I composed specifically for the documentary and other music was taken from my existing albums.

One last question, how can we get a chance to see German Sons?

German Sons is only available on Amazon US.

Harald, thank you so much for taking the time to meet and providing this wonderful and fascinating view into your musical world.

Filed under: Interviews

Related artist(s): Klaus Schulze, Sunya Beat, Ash Ra Tempel / Ashra, Harald Grosskopf, Wallenstein

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Release: Tashi Wada - What Is Not Strange?

Updated 2026-02-24 14:56:16 - Artist: Tashi Wada

Updated 2026-02-24 14:54:34 - Release: Greg Segal - Maintain!

Updated 2026-02-24 00:38:03 - Review: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Published 2026-02-24 - Review: Nektar - Mission to Mars & Fortyfied

Published 2026-02-23 - Review: Jaime Rosas - Tres Piezas de Rock Progresivo

Published 2026-02-22 - Release: Kevin Kastning & Bruno Råberg - Across Tall Rain

Updated 2026-02-21 00:42:08 - Review: Gary Husband - Postcards from the Past

Published 2026-02-21 - Release: Daniel Crommie - Februa

Updated 2026-02-20 14:23:17