Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

From Renaissance to Illusion —

A Profile of the Relf / McCarty Renaissance

The emergence of Renaissance in 1969 coincided with the birth of a new musical genre: Progressive Rock. The British rock scene was then in the midst of a highly creative period following the psychedelic era and the musical earthquake caused by the Beatles' landmark album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

by Aymeric Leroy, Published 1997-05-01

Chapter 1: Come Together...

Although the avant-garde of the progressive movement was represented by new groups such as King Crimson, some of the pioneers of the British blues-boom of previous years were still active: Manfred Mann and his Chapter 3 (later to metamorphose into the Earth Band) and Colosseum (a group of veterans of the blues-boom led by drummer Jon Hiseman). Under the influence of Cream and Jimi Hendrix, these musicians were hardening their sound, as well as integrating elements borrowed from more sophisticated genres such as jazz and classical music.

Keith Relf and Jim McCarty, vocalist and drummer respectively of the Yardbirds, rejected this decibel inflation when they left the band in July 1968. They had become uncomfortable with the direction espoused by their flamboyant guitarist, Jimmy Page. "At the time," remembers Jim McCarty, "Keith and I were into paranormal and psychic phenomena, UFOs, Buddhism, and stuff like that... Musically, we were evolving towards quieter styles such as folk and classical. It was the complete opposite of the heavy-blues that we had been playing over the last few years... It was a breath of fresh air."

Taking their inspiration from Simon & Garfunkel, Relf and McCarty formed the group Together, in which they both sang and played guitar. A few demos were recorded, followed by a single produced by former Yardbirds bassist, Paul Samwell-Smith and including the songs "Henry's Coming Home" and "Love Mom and Dad." A third song, "Together Now," was included later in the CD re-issue of the Yardbirds' Little Games. These are wonderful songs with psychedelic overtones and lush orchestration as was then the norm. The duo format, however, quickly became limiting, and by late 1968 Relf and McCarty decided to recruit new members. Through a common friend, they met session guitarist Pete Gage, a member of Ram Jam Band, and backup band singer Geno Washington. Gage, well connected in the musical milieu, was busy working with a young bassist with an already extensive resume, Louis Cennamo.

Taking their inspiration from Simon & Garfunkel, Relf and McCarty formed the group Together, in which they both sang and played guitar. A few demos were recorded, followed by a single produced by former Yardbirds bassist, Paul Samwell-Smith and including the songs "Henry's Coming Home" and "Love Mom and Dad." A third song, "Together Now," was included later in the CD re-issue of the Yardbirds' Little Games. These are wonderful songs with psychedelic overtones and lush orchestration as was then the norm. The duo format, however, quickly became limiting, and by late 1968 Relf and McCarty decided to recruit new members. Through a common friend, they met session guitarist Pete Gage, a member of Ram Jam Band, and backup band singer Geno Washington. Gage, well connected in the musical milieu, was busy working with a young bassist with an already extensive resume, Louis Cennamo.

Born March 5, 1946 from Italian parents, but living in London, Cennamo had been raised on his father's Italian record collection, and later had been exposed to the nascent rock scene by his older sister who was a fan of Chuck Berry and Ray Charles. At the young age of 17, he joined the Five Dimensions, a band from Birmingham in which Rod Stewart had made his singing debut. The band backed up Chuck Berry on the album Chuck Berry in London. "...But, we were not credited, so no one knew that we played on it!" After meeting vocalist Mike Patto during a festival during which Patto acted as compere between acts, they formed the short-lived Chicago Line Blues Band (1965-66) together with pianist Tim Hinkley. After a brief stint with The Herd, where he met a very young Peter Frampton, Cennamo began a career as a studio musician (the only single which he recorded with The Herd, "So Much In Love," flopped, but the following one was a huge hit!). He played, as a guest, on Jody Grind's first album, a trio founded by his old colleague Tim Hinkley. "At the time, we were like a family with the other musicians: Ivan Zagni, Barry Wilson, the guitarist and drummer in Jody Grind, and Boz Burrell, who was later in King Crimson and Bad Company." Thanks to The Herd organist, Andy Bown (later in Status Quo), Louis also found a job at a little West End club owned by Andy's girlfriend's mother. Still busy with session work, he played on the debut album (on the Beatles' Apple label) by budding singer James Taylor. Then at the end of 1968 Louis got a call from Pete Gage, and ended up attending the audition at Relf's house with him.

Actually, Relf and McCarty had also contacted their old Yardbirds colleague Chris Dreja with a view to having him to play bass in the new band. At that time, Dreja was trying to start a new country-rock group with steel guitarist B.J. Cole and pianist John Hawken. Born May 9, 1940 in Bournemouth, Hawken was known back then for his participation in the Nashville Teens between 1962 and 1968. In typical early Beatles fashion, the Teens, founded by Hawken and guitarist Michael Dunford, had spent a few months in Hamburg in 1963 (at which point they were briefly joined by vocalist Terry Crowe — more on him later). The Teens didn't have the talent or the luck of the Fab Four, however, and their career quickly declined after the mid-60s. Following several personnel changes, including the arrival of bassist Neil Korner at the end of 1967, Hawken began to lose interest, and decided to try something different alongside Chris Dreja. But, Chris' motivation quickly waned, and it wasn't long before he decided to focus on his hobby: photography.

So this small crowd of people ended up visiting Keith Relf's home, where Keith and Jim played some of their songs, joined by the other musicians for a little jam session. At one point, "Islands" was played, and John Hawken had the idea to add classical arpeggios to the song. The future style of Renaissance was already beginning to take shape.

A fruitful contact was quickly established between Relf and McCarty and Cennamo: "Keith, Jim, and I got along fine right from the beginning," remembers the bassist. "Their songs were very close to the kind of music which I was aspiring to play." Neither of the two guitarists present that day proved satisfactory. Actually, Relf and McCarty didn't really feel any need for a lead guitarist, being somewhat tired of guitar heroes after playing with Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Jimmy Page in the Yardbirds. The piano was thus assigned the leading role, with Keith Relf taking on guitar duties, in spite of his lack of expertise on the instrument. Keith's discomfort explains his subdued role on the band's future albums. An anecdote on this topic is instructive: during a concert tour in Scandinavia, where the band opened for John Mayall, the latter's band missed a gig. Mayall turned to Relf and McCarty for backup, and was surprised to see Relf playing simple rhythm accompaniment, only attempting timid solos when his back was turned to the audience...

Chapter 2: A Meteoric Career

In January of 1969, the quartet began rehearsing in Jim McCarty's house. But something was still missing... Jane, Keith's sister, who as a backing singer had participated in the sessions for the Together single, was anxious to join the new band. "Everything seemed to gel," says McCarty. "Her image meshed perfectly with what we were looking for." As far as her vocals were concerned, the reviews were a bit mixed: "At the time, her voice was a bit rough, lacking experience," notes Louis Cennamo, "but she had a magical side which pleased us a lot."

The rehearsals took place in a very idyllic and egalitarian atmosphere. "We all had very strong links with each other," explains Cennamo, "we got along extremely well as people. A very pleasant memory." The group was entirely democratic; all contributed and enriched the others. "It was a very innocent, happy, and creative period. We were all happy to be doing something different from what had been done before."

The compositions were written jointly by Relf and McCarty. The latter had just acquired a piano that allowed him to improve his knowledge of harmony. The pair would arrive at the sessions with some lyrics and a few riffs. After some intense collective work, classically-inspired instrumental sections, mostly worked out by Cennamo and Hawken, would be added to Keith and Jim's often embryonic songs.

Through this process, the first album was completed during the summer of 1969 at Olympic studios in London under the direction, once again, of Paul Samwell-Smith. The technical means available to the group (modest by today's standards: one 8-track mixing table as opposed to the Yardbirds' 4-track) gave the musicians the freedom to experiment and innovate.

Through this process, the first album was completed during the summer of 1969 at Olympic studios in London under the direction, once again, of Paul Samwell-Smith. The technical means available to the group (modest by today's standards: one 8-track mixing table as opposed to the Yardbirds' 4-track) gave the musicians the freedom to experiment and innovate.

The album was well received, especially in the States where the band did an extensive tour in early 1970. In order to book these concerts, the bands took advantage of the notoriety of the Yardbirds. This was a strategic mistake in that the band ended up on the "psychedelic / blues" circuit where the public expected to hear heavy blues songs with 3 chords and 12 bars. Indifferent, and sometimes hostile, to the sophistication of the band's music, the audiences didn't really 'get into' it. Back to square one! Times had changed since the days where a few hours of rehearsal were all that was needed to prepare for a concert. "We played together a lot," says McCarty. "The numbers were arranged very precisely. It was very complicated, compared to the Yardbirds' music. The result was that we were a good band on stage, but it really required a huge amount of work." These early concerts started with the sounds of a plane taking off. Then the band would begin to play "Kings and Queens," followed by the whole of the first album. "We wouldn't play any Yardbirds songs," says McCarty. "Mainly extended versions of the album tracks, as well as a half-improvised track named 'McKay's Rave,' in the style of Santana."

Despite the joy of performing, the concerts followed each other at such a pace that the group's morale began to suffer. "It became a routine, and soon, all the pleasure was gone out of it," explains Louis Cennamo.

"One of the reasons I left the Yardbirds was the exhaustion from incessant touring," adds McCarty, "and suddenly it was happening all over again. Keith and I felt we were losing control of the situation. We were under enormous pressure each night. In addition, communication problems began to arise inside the band. John was a bit pushy, and Jane was becoming more and more prickly. I was very tense, and after a while, I couldn't stand the idea of getting up on a stage anymore."

A tour to Switzerland was subsequently cancelled, and, once back to England, the members of the band all went their own way. "That for sure was a big mistake, looking back on it," Cennamo comments. "We should have stayed together, but we didn't, and that precipitated the demise of the group." However, the breakup would have to wait since the group had a contractual obligation to record one more album for Island. They gathered again at the Olympic studio during the spring of 1970.

On two of the album's songs, lyrics are credited to one Betty Thatcher, who would subsequently become Renaissance's lyricist. It was Jim McCarty's idea to call upon her, finding it difficult to write good lyrics himself. Thatcher was a friend of Jane Relf's from the time when she lived in Cornwall. Interestingly, her collaboration with the group, whether it be with McCarty, or, later on, with Mike Dunford, was always done remotely, with the bands sending her cassettes of musical ideas on which she would overlay her lyrics.

Keith Relf and Jim McCarty decided to cease being performing members, and to concentrate on composing. John Hawken called upon his old buddies from the Nashville Teens, Terry Crowe (vocals) and Michael Dunford (guitar) to replace Relf, and recruited session drummer Terry Slade to take McCarty's slot.

During the summer of 1970, as the group was about to start in its new configuration, the band Colosseum, whose bassist had just left to become a producer, contacted Louis Cennamo. With the future of Renaissance most uncertain, and the offer being appealing in terms of both prestige and money, Cennamo quickly accepted. His time with the band, whose style was quite a bit different from Renaissance's, would turn out to be quite short, but it gave him the opportunity to perform at numerous concerts in Europe and England; most notably at the Bath festival in front of 250,000 spectators. He also played on the Daughter of Time album. "Eventually, it appeared that I didn't really fit in with the group's style, which was too 'heavy' for me compared to Renaissance. In addition, I was not taking part in the writing. I was just a player, and it felt a bit robotic."

To fill this gap, Hawken called upon another old acolyte, Neil Korner. With this new line-up, whose only original members were Jane Relf and himself, Hawken recorded a Dunford composition: "Mr. Pine." Since there was an insufficient amount of material for the album, the original Renaissance re-assembled temporarily (strangely enough, without John Hawken, who was replaced by session musician Don Shin) to record "Past Orbits of Dust." Even though it contained somewhat of a hodgepodge of material, the album was complete!

To fill this gap, Hawken called upon another old acolyte, Neil Korner. With this new line-up, whose only original members were Jane Relf and himself, Hawken recorded a Dunford composition: "Mr. Pine." Since there was an insufficient amount of material for the album, the original Renaissance re-assembled temporarily (strangely enough, without John Hawken, who was replaced by session musician Don Shin) to record "Past Orbits of Dust." Even though it contained somewhat of a hodgepodge of material, the album was complete!

Island Records was less than enthusiastic, though. Aware of the success of other Yardbirds alumni (Led Zeppelin, Jeff Beck, not to mention Eric Clapton), the label was expecting a lot from this second album, and had turned up the pressure on the musicians. Island felt that Illusion, which they kept on a shelf for several months, was inferior to the first album, and lacked energy.

At the end of the summer of 1970, Renaissance gave a few concerts, after which Jane Relf left the band. For five years, she rarely broke her silence, only occasionally singing in commercials. An American singer Binky Cullom, replaced her for a while, but Hawken was not satisfied, so he left to join Spooky Tooth's fall 1970 tour.

At that point, Renaissance had lost all of its original members, and seemed destined to disappear. Michael Dunford, however, had other ideas. After leaving the Nashville Teens, he had formed several groups, none of which had met with much success, and then had retired to focus on composition. For him, Renaissance was a means to finally use his work. He took over the reins of the band, with the theoretical assistance of Jim McCarty and Keith Relf. The latter, more and more involved with his work as a producer at Bradley Records, began to withdraw from the band. McCarty on the other hand remained active writing songs and playing at concerts. He was therefore present when auditions to replace the departing American vocalist were held. When in January of 1971, Annie Haslam, a young cabaret singer responded to a classified add in a music journal, McCarty immediately recognized in her an extraordinary talent, and he strongly encouraged Dunford to pick her. What intuition! A new era was beginning for Renaissance...

Chapter 3: Worlds Apart

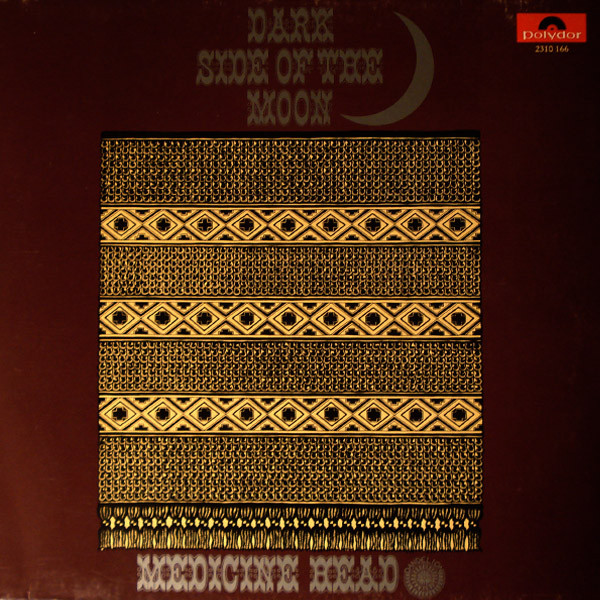

Even though they had gone their separate ways, the members of the original Renaissance remained active. Keith Relf, through his work as a producer became involved with a folk duo named Medicine Head formed by John Fiddler (voice, guitar) and Peter Hope-Evans (voice, etc.). When Peter left the band, Relf replaced him as a second vocalist, also playing guitar or bass (drummer John Davies later joined to make it a trio). They recorded an album: Dark Side of the Moon (a year before Pink Floyd!) which met with limited interest. Relf then retired from the band to make room for the returning Hope-Evans.

Even though they had gone their separate ways, the members of the original Renaissance remained active. Keith Relf, through his work as a producer became involved with a folk duo named Medicine Head formed by John Fiddler (voice, guitar) and Peter Hope-Evans (voice, etc.). When Peter left the band, Relf replaced him as a second vocalist, also playing guitar or bass (drummer John Davies later joined to make it a trio). They recorded an album: Dark Side of the Moon (a year before Pink Floyd!) which met with limited interest. Relf then retired from the band to make room for the returning Hope-Evans.

During this period, Relf had stayed in contact with McCarty. After the latter had started his own band, Shoot, Relf would sometimes handle the sound at concerts. In return, McCarty would attend sessions organized by his old colleague. Shoot was born of Jim McCarty's desire to play some of his own compositions after spending a year and a half writing for others (for Renaissance, but also for others such as Jane Relf's single). In addition to singing, he chose to play piano rather than drums in order to facilitate concerts. Dave Green (guitar, vocals), Bill Russell (bass), and Craig Collinge (drums) filled out the band. They signed with EMI and recorded an album, On the Frontier (1973), named after a McCarty-Thatcher composition which would also find its way that same year on the second album by the new Renaissance.

But artistic as well as commercial success remained elusive, and Shoot broke up after having been jettisoned by its label. There followed a period of inactivity for McCarty, about which, he confesses, he does not remember much besides that it marked the end of his collaboration with Renaissance, after a final contribution, "Things I Don't Understand," co-written by Dunford. "I ended up realizing that they could manage just fine without me," he explains, "I felt that my presence was unnecessary, so I left."

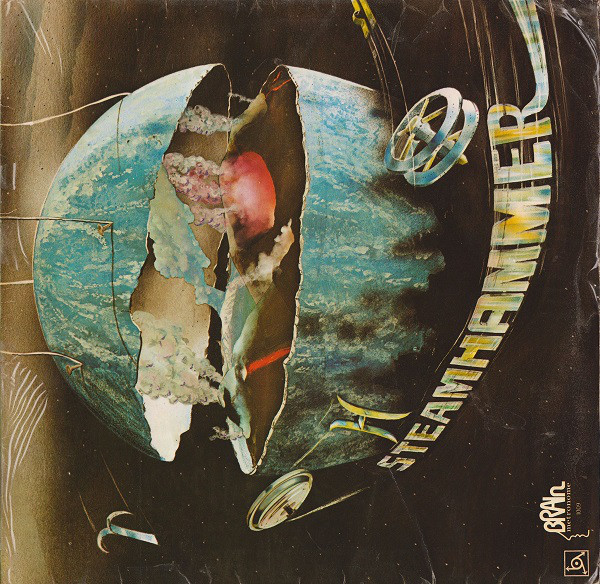

After leaving Colosseum, Louis Cennamo briefly played with Bogomas, a band where he met up again with Ivan Zagni (guitar) and Barry Wilson (drums) of Jody Grind. "We didn't play any gigs, we just rehearsed. We would play so-called 'progressive' instrumental music with a lot of self-indulgent solos. In spite of Island's Chris Blackwell's interest, we were lacking funds, so I left to join Steamhammer in early 1971."

At that time, the band was looking for a replacement for Steve Davy. "We evolved the music from R&B to something more adventurous and sophisticated. My relationships with other members of the band were excellent. We did a lot of touring, especially in Germany, but also in the rest of Europe. What else could you ask for? To be in a band, and to see the world!" Cennamo played on the This Is album (also known as Speech), which had only moderate success. "It was a strange album," he comments, "a bit of a mess!" Moreover, it was released under dramatic circumstances due to drummer Mickey Bradley's death during the mixing in early 1972, of a lightning-fast leukemia. Cennamo and Steamhammer guitarist Martin Pugh decided to form a new instrumental band: Axis, with original Steamhammer guitarist Martin Quittenton, a collaborator of Rod Stewart's. They spent some time composing and rehearsing, but, due to poor management, they broke up at the end of 1973 without having recorded anything.

At that time, the band was looking for a replacement for Steve Davy. "We evolved the music from R&B to something more adventurous and sophisticated. My relationships with other members of the band were excellent. We did a lot of touring, especially in Germany, but also in the rest of Europe. What else could you ask for? To be in a band, and to see the world!" Cennamo played on the This Is album (also known as Speech), which had only moderate success. "It was a strange album," he comments, "a bit of a mess!" Moreover, it was released under dramatic circumstances due to drummer Mickey Bradley's death during the mixing in early 1972, of a lightning-fast leukemia. Cennamo and Steamhammer guitarist Martin Pugh decided to form a new instrumental band: Axis, with original Steamhammer guitarist Martin Quittenton, a collaborator of Rod Stewart's. They spent some time composing and rehearsing, but, due to poor management, they broke up at the end of 1973 without having recorded anything.

In February 1974, Cennamo got a phone call from Keith Relf, with whom he had remained in contact, asking him what he was up to, and whether he was interested in coming out to California! "I was instantly excited by the idea," remembers Cennamo, "I had kept fond memories of Renaissance's tour over there. We were both attracted to that land, and, even though we had little money, we decided to try our luck. Also, from a personal viewpoint, I needed to move on because my father had just died, and I was feeling down."

Relf, Pugh, and Cennamo found themselves in L.A., where they acquired lodgings thanks to friends from the time of Renaissance's American tour. They ran into a very good drummer-vocalist named Bobby Caldwell, who had played with Johnny Winter. "We began rehearsing, and, without having really built a repertoire, we went to A&M's offices to ask them if they would be interested in hearing us," says Cennamo. "They invited us in, and we played them some fairly improvised stuff. Because we sounded very dynamic, and Keith was still well known as the ex-singer of the Yardbirds, we were able get a contract without too much trouble."

The new band, Armageddon, went to work rehearsing in a studio gracefully made available by A&M, but they soon ran into trouble. It appeared that Bobby Caldwell was having drug problems that quickly began to have a negative influence on their work. When Martin Pugh also fell prey to drugs, the group split into two parts. Relf and Cennamo became interested in the "spiritual" side of L.A., studying yoga and meditation. "Keith and I had become very close at that time," comments the bassist, "We experienced some really crazy things together."

The new band, Armageddon, went to work rehearsing in a studio gracefully made available by A&M, but they soon ran into trouble. It appeared that Bobby Caldwell was having drug problems that quickly began to have a negative influence on their work. When Martin Pugh also fell prey to drugs, the group split into two parts. Relf and Cennamo became interested in the "spiritual" side of L.A., studying yoga and meditation. "Keith and I had become very close at that time," comments the bassist, "We experienced some really crazy things together."

The band still had a contractual obligation to record an album, so, after six months in California, the quartet returned to London in December of 1974. The sessions were held at the old Olympic studios. "The band was clearly going downhill," says Cennamo, "Personal difficulties kept affecting the rehearsals, and my playing was getting worse and worse as a result."

The Armageddon album, in spite of its difficult birth, is an artistic success. The musical style, with its emphasis on the guitar of Martin Pugh, is the complete antithesis of the classical intimacy of Renaissance. But the band doesn't limit itself to playing hard rock: the progressive spirit remains very present in the complex "Buzzard" and the very beautiful "Silver Tightrope." Nonetheless, there is no hint that, just a few months later, Relf and Cennamo would again embrace the refinement of their old group.

Chapter 4: The Homecoming: Illusion

Soon after the end of the recording sessions, Keith Relf decided that he'd had enough, so he and Louis left Armageddon, which then ceased to exist. Drummer Bobby Caldwell would go on to a successful solo career as singer.

"A few months later, during the fall of 1975, Keith and Jane came to see me," Cennamo adds, "They wanted to reform Renaissance due to the ongoing public interest in the first two albums. Since I wasn't doing much besides a few sessions here and there, I accepted. We then called Jim and John, who both agreed to join us."

Since his departure from Spooky Tooth, John Hawken had played with Vinegar Joe (1971-72), the band started by Pete Gage and Steve York with Robert Palmer and Elkie Brooks on vocals. He also played keyboards for the Strawbs from 1973 to 1975 (on the Hero and Heroine and Ghosts albums). As in the good old days, the five musicians would meet at Jim McCarty's place. "It was great," remembers Jim, "Since we had all played together before, it didn't take us long to get back into the groove. We went to work." The end of 1975 and the beginning of 1976 were spent composing and recording demos of new songs, as well as touring the labels, without much success. Looking back on this period, Jim McCarty reckons things weren't advancing as fast as he would have liked. He and Keith somehow failed to find the same creative osmosis that they'd had in the early days of Renaissance. He also thought that the new tracks weren't as good as the old ones.

But those feelings were laid to rest when on May 14th 1976, tragedy struck: Keith Relf was found dead in his Whitton apartment by his 4-year old son. He was lying on the floor holding a guitar. "He used to play with earphones on so nobody could hear him at night, and he apparently fell victim to an electrical short" comments Jim McCarty, who had dined with Relf the night before.

One would think that Keith Relf's death would doom all attempts to recreate Renaissance, but, on the contrary, this loss galvanized and further inspired the remaining members. After a short hesitation, they began rehearsing again with newfound fervor. "In some way, we did so as a tribute to Keith," adds Cennamo. Jim McCarty took over the male vocals, a role which really mattered to him, and which was probably instrumental in the ex-drummer's renewed energy. Two new musicians were brought in to round out the band: John Knightsbridge (guitar), a friend of John Hawken who met him during sessions for the Third Wolrd War band, and Eddie McNeil (drums), an Australian ex-pat who had been a member of the Scottish band Strange Days. The name Illusion was suggested by Jane Relf at that point. "We had begun to rehearse together," continues Louis Cennamo, "We recorded a demo of six songs in July of 1976, including 'Isadora' and 'Solo Flight.' We took the tape to the folks at Islands Records."

"Someone once told me that the best way to get a contract was to speak to the record labels from whom you were receiving money," smiles McCarty. " And that's what we did!" Tim Clark, the head of the label, fell in love with the songs, and signed Illusion on the spot.

In the fall, a first album was completed at Island studios in Hammersmith, near London. All the songs were written by McCarty, with the exception of four co-written by John Hawken. For the first time, the group used orchestral arrangements for which they called upon Robert Kirby, who was renowned for his work with the Strawbs and on Nick Drake's magnificent first two albums.

In the fall, a first album was completed at Island studios in Hammersmith, near London. All the songs were written by McCarty, with the exception of four co-written by John Hawken. For the first time, the group used orchestral arrangements for which they called upon Robert Kirby, who was renowned for his work with the Strawbs and on Nick Drake's magnificent first two albums.

The musical style had evolved from the Renaissance days. "We were trying for something a bit different, with a bit more of a "middle of the road" feel, a mixture of ballads and rockers, with a heavier guitar sound," explains Louis Cennamo. "Unfortunately, I was unable to invest as much time as I would have liked in the band given my interest in spirituality at that time, which led me to travel to India regularly. The real energy in the band came from Jim and Jane. Jane, in particular was at the peak of her vocal powers. Overall, it was an enriching period for me, but less creative than that of Renaissance."

The release of Out of the Mist was followed by an extensive tour throughout Europe, with the band opening for Bryan Ferry. Sales figures for the album were modest, but the critics were generally enthusiastic, and the concerts reinforced the band's renown. Besides the tracks from the album, and a few Renaissance classics, the stage performances also included Kim Fowley's famous composition, "Nutrocker" (already covered by E.L.P. on their Pictures at an Exhibition album), during which Jim McCarty would join McNeil on a second set of drums, Genesis style.

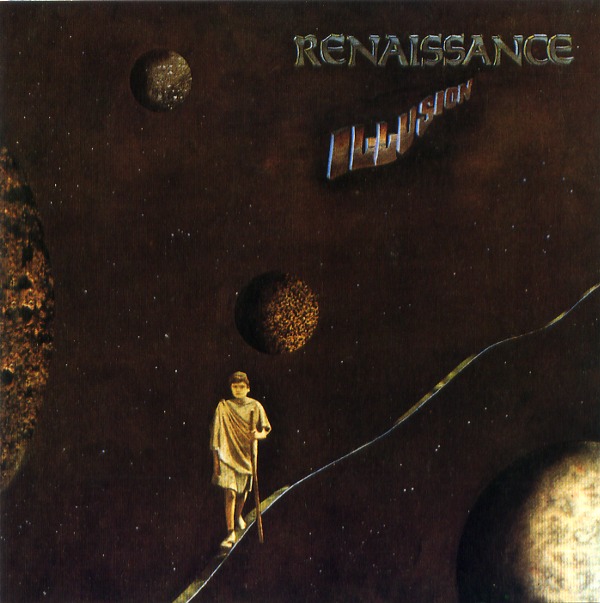

At the time when Illusion began work on their second album, England was in the middle of the punk explosion. Music labels followed the trend, signing "promising" new bands by the dozen. While Virgin made millions of pounds with the Sex Pistols, Island was welcoming bands such Ultravox and Eddie and the Hot Rods in its ranks. Only Tim Clark remained faithful to Illusion and Paul Samwell-Smith who produced the eponymous second album. "We really enjoyed doing this album with Paul as producer," remembers McCarty. "But due to the pressure and the touring," he adds modestly, "I felt the material was not as strong as on the first album, although it did contain the classic track 'Madonna Blue,' which brought out the very best of everyone in the band."

At the time when Illusion began work on their second album, England was in the middle of the punk explosion. Music labels followed the trend, signing "promising" new bands by the dozen. While Virgin made millions of pounds with the Sex Pistols, Island was welcoming bands such Ultravox and Eddie and the Hot Rods in its ranks. Only Tim Clark remained faithful to Illusion and Paul Samwell-Smith who produced the eponymous second album. "We really enjoyed doing this album with Paul as producer," remembers McCarty. "But due to the pressure and the touring," he adds modestly, "I felt the material was not as strong as on the first album, although it did contain the classic track 'Madonna Blue,' which brought out the very best of everyone in the band."

Anyway, the fans will note the presence of a track composed by Louis Cennamo and Jane Relf (a debut composition credit for both), "Louis' Theme," as well as a track from 1975 co-signed by Keith Relf, "Man of Miracles."

The second album, unlike the first, didn't have any effect on the media, in spite of a European tour opening for Dory Previn. Worse, it was not even issued in the States, a vital country for the band. Needless to say this was a big disappointment, and got even worse when Island terminated Illusion's contract. The band, as in its early days, began contacting indifferent music label, but unfortunately none believed in the commercial potential of Illusion's music.

Jim McCarty, now in charge of the band's musical direction, financed a number of recording sessions with the intent of presenting the demos to the labels. But the band's motivation was waning. McNeil was the first to quit, followed by John Hawken, a pillar of the group who has hardly been heard of since. Although a replacement was found for Hawken and McCarty came back to the drummer's stool, the end was near. Illusion would not see the decade out.

Jim McCarty, now in charge of the band's musical direction, financed a number of recording sessions with the intent of presenting the demos to the labels. But the band's motivation was waning. McNeil was the first to quit, followed by John Hawken, a pillar of the group who has hardly been heard of since. Although a replacement was found for Hawken and McCarty came back to the drummer's stool, the end was near. Illusion would not see the decade out.

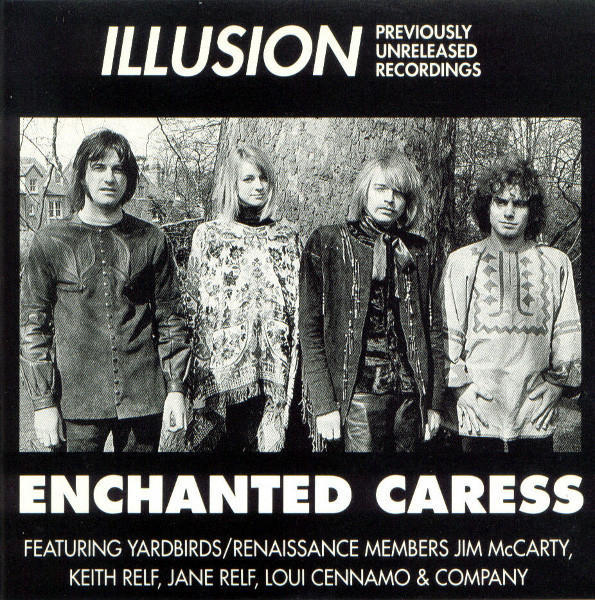

Ten years after their recording, a number of tapes from the latter days of Illusion (recorded in 1979, shortly before Hawken's departure) were uncovered in Jim McCarty's attic, and released on a CD titled Enchanted Caress, 1990. These nine tracks (supplemented by "All the Falling Angels," Keith Relf's last recording from 1975) go further in a mainstream direction, with the classical influence and sophisticated arrangements largely gone. The focus here is on the vocals, superb as always, although serving a less interesting musical content. Still there are moments of magic, such as "The Man Who Loved the Trees," a ballad sung by Jane to Hawken's piano accompaniment in the grand tradition of Illusion, or the instrumental "Slaughter on Tenth Avenue."

Epilog: Stairway and Pilgrim

Since the dissolution of Illusion, its former members have worked in different areas, but without ever losing track of each other. Jim McCarty returned to his first love: rock & roll, playing with John Knightsbridge and Rod Demick, and with various bands composed of ex-Yardbirds (Box of Frogs and more recently the Yardbirds / Pretty Things all-star band), or 60s celebrities (the British Invasion All-Stars). Louis Cennamo retired from the world of music to focus on the spiritual quest that he began in the mid-70s. He nevertheless recorded a solo album, Diamond Harbour, in 1982, which was only released on a limited-edition cassette. He now goes by the name "Loui" because his American friends, unaware that the "s" is silent, would insist on pronouncing it "Lewis." "I like to play with spellings when I'm in the mood," says he with a smile. Louis is currently working on a solo guitar project in the relaxation music genre. Jane Relf and went off to live with her family in the countryside, only occasionally returning to music. A solo project was announced several times, but never appeared.

Since the dissolution of Illusion, its former members have worked in different areas, but without ever losing track of each other. Jim McCarty returned to his first love: rock & roll, playing with John Knightsbridge and Rod Demick, and with various bands composed of ex-Yardbirds (Box of Frogs and more recently the Yardbirds / Pretty Things all-star band), or 60s celebrities (the British Invasion All-Stars). Louis Cennamo retired from the world of music to focus on the spiritual quest that he began in the mid-70s. He nevertheless recorded a solo album, Diamond Harbour, in 1982, which was only released on a limited-edition cassette. He now goes by the name "Loui" because his American friends, unaware that the "s" is silent, would insist on pronouncing it "Lewis." "I like to play with spellings when I'm in the mood," says he with a smile. Louis is currently working on a solo guitar project in the relaxation music genre. Jane Relf and went off to live with her family in the countryside, only occasionally returning to music. A solo project was announced several times, but never appeared.

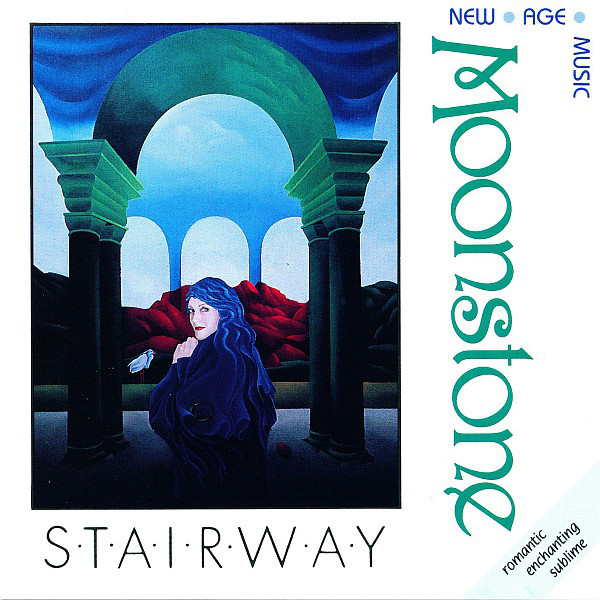

All three have been involved in a somewhat episodic band named Stairway, which began in 1985 under unexpected circumstances. "I called Louis to ask him to play bass at Box of Frogs concerts," McCarty remembers. "He was celebrating his birthday the next day, so he invited me over to his place. We had a long chat during which we discovered a common interest in healing music. We were later introduced to Colin Wilcox of New World Tapes, and decided to record some music together, with myself on keyboards, Louis on guitar and Clifford White on keyboards too. We released four cassettes between 1987 and 1992. On Aquamarine (1987) and Moonstone (1988), Jane contributed to the singing. Sadly, she lived too far from here to become more involved." She was therefore absent during the few Stairway concerts given at St. James' Church in Piccadilly, London (a video of which is available).

All three have been involved in a somewhat episodic band named Stairway, which began in 1985 under unexpected circumstances. "I called Louis to ask him to play bass at Box of Frogs concerts," McCarty remembers. "He was celebrating his birthday the next day, so he invited me over to his place. We had a long chat during which we discovered a common interest in healing music. We were later introduced to Colin Wilcox of New World Tapes, and decided to record some music together, with myself on keyboards, Louis on guitar and Clifford White on keyboards too. We released four cassettes between 1987 and 1992. On Aquamarine (1987) and Moonstone (1988), Jane contributed to the singing. Sadly, she lived too far from here to become more involved." She was therefore absent during the few Stairway concerts given at St. James' Church in Piccadilly, London (a video of which is available).

Musically, Stairway is firmly in the "new-age" category. Compositions are built on relatively simple melodic themes which are repeated in order to induce a state of well-being. If you listen to it without being in the right mood, it may seem completely empty, but this impression is deceptive. While not masterpieces by any standards, Stairway's releases do have interesting moments, especially when Jane Relf contributes vocals (the music is mostly instrumental, with McCarty providing occasional singing as well). Stairway's latest release is Raindreaming (1994), actually recorded in 1989, and including some truly moving moments, for instance the song "Moonlight Skater" sung by Jane Relf.

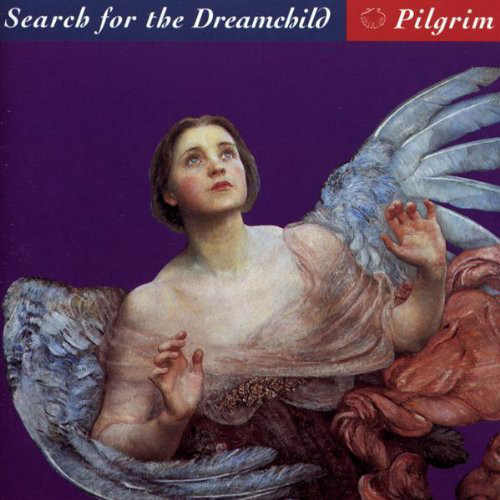

In 1994, Jim McCarty released his first solo album, Out of the Dark, a fairly mainstream soft-rock album which was again interesting mostly for the vocal aspect, with Jane Relf duetting on a couple of tracks to good effect. He also leads a new project, Pilgrim, with John Richardson and Tania Matchett on vocals, still in a quiet, meditative vein, but with a higher level of musical substance. Pilgrim's two albums, Search for the Dreamchild (1995) and Gothic Dream (1996), display influences from both classical and medieval music, and are a mix of songs and instrumentals. Lyrics are provided by Carmen Willcox, director of the New World Music label, although most of those on Gothic Dream are taken from the works of great romantic poets (Keats, Byron, Shelley and Poe).

In 1994, Jim McCarty released his first solo album, Out of the Dark, a fairly mainstream soft-rock album which was again interesting mostly for the vocal aspect, with Jane Relf duetting on a couple of tracks to good effect. He also leads a new project, Pilgrim, with John Richardson and Tania Matchett on vocals, still in a quiet, meditative vein, but with a higher level of musical substance. Pilgrim's two albums, Search for the Dreamchild (1995) and Gothic Dream (1996), display influences from both classical and medieval music, and are a mix of songs and instrumentals. Lyrics are provided by Carmen Willcox, director of the New World Music label, although most of those on Gothic Dream are taken from the works of great romantic poets (Keats, Byron, Shelley and Poe).

In the last few years, there has been insistant talk of the original Renaissance reforming (minus Keith Relf of course) at the instigation of a German record label. This is an idea both McCarty and Cennamo seem keen on, although this is yet prevented by practical difficulties, with John Hawken residing in America (although there is word of him returning to live in England) and Jane Relf living with her family in a remote Yorkshire village.

Filed under: Profiles, Issue 12

Related artist(s): Strawbs, Annie Haslam, Renaissance, Colosseum, Illusion, Jody Grind

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Release: Tashi Wada - What Is Not Strange?

Updated 2026-02-24 14:56:16 - Artist: Tashi Wada

Updated 2026-02-24 14:54:34 - Release: Greg Segal - Maintain!

Updated 2026-02-24 00:38:03 - Review: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Published 2026-02-24 - Review: Nektar - Mission to Mars & Fortyfied

Published 2026-02-23 - Review: Jaime Rosas - Tres Piezas de Rock Progresivo

Published 2026-02-22 - Release: Kevin Kastning & Bruno Råberg - Across Tall Rain

Updated 2026-02-21 00:42:08 - Review: Gary Husband - Postcards from the Past

Published 2026-02-21 - Release: Daniel Crommie - Februa

Updated 2026-02-20 14:23:17