Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

A Band of Composers —

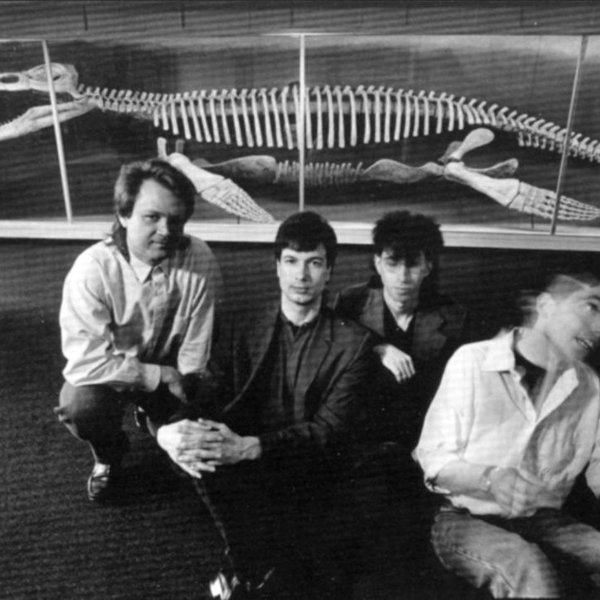

The Birdsongs of the Mesozoic Interview 1995

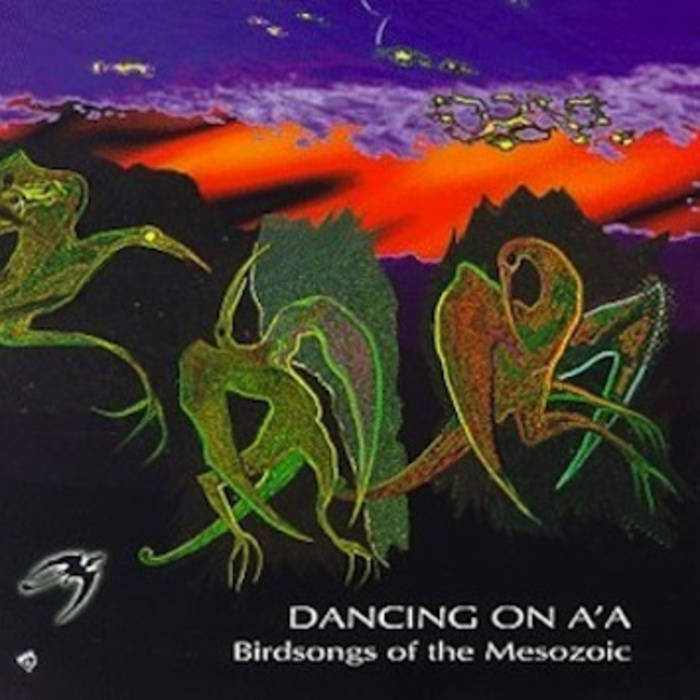

Birdsongs of the Mesozoic originally formed in the early 80s as a collaboration between Mission of Burma's Roger Miller and Boston composer Erik Lindgren. Though the band has undergone several personnel changes, including Miller's departure from the group, the one constant over the years has been their unique, eclectic blend of avant-garde, 20th century classical, electronic, and progressive musics. Their latest album on Cuneiform, Dancing on A'a, is their strongest one to date, full of complex, dynamic, and innovative compositions. I recently had the chance to speak with saxophonist Ken Field and guitarist Michael Bierylo.

by Rob Walker, Published 1995-11-01

I guess I'll start with something about which I'm always curious with bands that play what I generally think of as highly composed or "complex" music: when one of you writes a piece and then brings it to the ensemble as a whole, how much does the group then work out and modify the music into its final form? For example, I imagine that most of the aspects of the composition itself – the themes, counterpoint, rhythms, and the overall musical form would remain virtually unchanged, but that a fair amount of arranging and orchestrating might take place to experiment with the various timbral combinations available with Birdsongs' instrumentation.

I guess I'll start with something about which I'm always curious with bands that play what I generally think of as highly composed or "complex" music: when one of you writes a piece and then brings it to the ensemble as a whole, how much does the group then work out and modify the music into its final form? For example, I imagine that most of the aspects of the composition itself – the themes, counterpoint, rhythms, and the overall musical form would remain virtually unchanged, but that a fair amount of arranging and orchestrating might take place to experiment with the various timbral combinations available with Birdsongs' instrumentation.

KF: This is a bit different for each of the composers in the group. Erik is the most experienced composer, and he generally brings in the most fully thought-out pieces. We will work with him on actual performance issues (like that a particular passage is problematic on a certain instrument, or for a certain performer), and he will rework things based on this (and other, more artistic) feedback. Erik's pieces often have some element of improvisation, and this might involve some back and forth between the person doing the improvisation and Erik; the improvised part will end up settling in (after a fair amount of rehearsal) to the kind of sound Erik was looking for. I am a little less secure in my pieces (few and far between as they may be). I will usually put the piece into my notation program on my Mac so that I can listen to a sequenced version before bringing it in. But the sequenced version is not at all the same as live performers, so I will usually hear changes once the group tries it out, and I will solicit input for changes, development, or rearrangement. Michael is somewhere between Erik and me. He brings in computer-generated parts, and goes back and reworks things a fair amount, but he is more clear than I am on what he wants before he hears the group try out the piece.

So you feel that the process of composition involves not only writing the music you hear in your head, but also consciously tailoring certain aspects of that composition to the intended performers?

So you feel that the process of composition involves not only writing the music you hear in your head, but also consciously tailoring certain aspects of that composition to the intended performers?

MB: In the case of "new music" where the barriers of style are theoretically nonexistent, one must write for the individual or the ensemble. The best of new music plays on the strengths and dialects of individual performers. Take, for example, "new music" around 1945 by Duke Ellington. Here was a body of work composed for specific players in a specific ensemble. Certainly Raymond Scott's or Charles Mingus' ensembles personified this. A more recent example might be the Kronos Quartet which over its history has spawned much new composition by merely existing and providing composers with a stable model of 20th century string performance. In contrast to this might be Frank Zappa's iconoclast "I wrote it, you figure out how to play it" attitude which has been the model for many 20th century composers.

In Birdsongs' case, I think this model holds as the ensemble serves as a kind of composers' forum. Although the musicianship is relatively high, It certainly is not a group that is able to successfully read and perform anything put in front of it. Hence, the most successful compositions, are to me, the ones that play directly to the strengths of the individual members. In this case, the composer's job is not to write what needs to be heard, rather what needs to be heard from Rick Scott or Ken Field. I guess to me, the best new music is notating and organizing what the performer would play anyway. What makes Birdsongs' music interesting to me is that each performer has such a divergent background that when they merge something completely new happens.

Did the group have any specific goals when you got together to start work on the latest album; any elements of your previous work that you wanted to focus on more, or any new aspects you wanted to introduce?

MB: When I joined the group in 1990 much of my job was not only to learn the existing body of repertoire but also to establish my own voice, both as a player and compositionally, within the group. I think one of the things that changed in the group was that the guitar was used for melody more. In the past, the guitar had been used to add edge and texture to the music as this was Mr. Swope's forte. This was also something the group that we didn't want to lose and on A'a we've made a conscious effort to retain. I guess part of joining Birdsongs was to assimilate some of Martin Swope's style.

As far as other goals for A'a, the thing that you have to understand is that I think for us, recording is like taking a snapshot of where the group is at a particular point in time. We had certain broad sonic goals which our engineer and co-producer Bill Carmen helped tremendously in focusing on, but musically this was material which we had been performing for about two years when we had started to record. This in some way is the opposite to the standard write / record / tour cycle that has evolved in rock music. I would say that perhaps broad unspoken goals might include compositions which are entertaining, challenging, and have an aggressive edge to them at times. As composers of our generation, we must in some way deal with the music that surrounds us. I somehow could not write music that completely ignored the fact that I spent hours rapt by Jimi Hendrix' "Machine Gun" or the Mahavishnu Orchestra's Birds of Fire or the Clash's Sandinista. In this sense I, and I think the group as a whole, are very pleased with the snapshot that came out.

KF: We were very happy with the previous CD, Pyroclastics. I think we were looking with Dancing on A'a to continue that direction. In addition, we had new pieces coming from a slightly different place due to the fact that Michael had joined the group, and we wanted to integrate those new influences that he had brought with him.

What were some of those new influences that Michael brought? The music of Birdsongs contains so many diverse elements; I'm curious what specific influences you, Erik, and Rick each individually bring to the group?

KF: Michael is heavily into things like Bulgarian folk music and Senegalese music (both Michael and I spent time playing in a Boston-based Senegalese band). He brings rhythmic and melodic concepts from these types of music. One interesting thing is that the rhythmic concepts are not necessarily simple (as one might naively expect); he pulls lots of time changes into his compositions, for example, and they are not gratuitous; they are often used to follow lyric-type melodic lines, as they are in some folk music.

Erik is more into contemporary classical forms and composition, though I don't really know enough about this to speak intelligently about it. I am into melodically-based, rhythmic music. I do not play (with any proficiency) any chordal instrument, so my compositions tend to be layered melodies, with the harmony falling out from, rather than dictating, the melodies.

Technology is obviously important to the sound of Birdsongs, with the sequenced rhythms, electronic percussion, and various samples and effects; do you experiment with many of the new boxes and electronic gadgets that come out to find new things to complement or expand the group's sound?

KF: Actually, I think we experiment with new toys surprisingly little. We are pretty aware of what's available (Rick is involved in his other life with high-end pro audio equipment, and Michael teaches electronic music at Berklee), but we don't have a lot of money to throw at buying every new item that comes along. I think this is good, because I think it is too easy to get diverted from just making good music.

KF: Actually, I think we experiment with new toys surprisingly little. We are pretty aware of what's available (Rick is involved in his other life with high-end pro audio equipment, and Michael teaches electronic music at Berklee), but we don't have a lot of money to throw at buying every new item that comes along. I think this is good, because I think it is too easy to get diverted from just making good music.

MB: Contrary to popular belief, Birdsongs is really a pretty low tech group in that we're in some ways well behind the curve of what's hot in music technology. I think it's important to understand that Birdsongs is a chamber group. We see ourselves more in the genre of a Kronos Quartet or Philip Glass ensemble (now you want to talk tech!) than a rock band. In this sense, I think we use technology as an influence more than tools at times. Part of the musical vernacular of our time is sample loops. We want to use these as structural elements in composition. MIDI, at this point is really low tech. It's been around long enough and has been used by pop / rock touring acts since the day it came out. Nothing new here. Writing for technology is much the same as writing for musicians, you have to figure out what it's good at and write to its strengths. Computers are quite good at organizing time based tasks, in that sense they are good at setting up a rhythmic grid or framework for a composition. Computers are really bad at giving expressive, spontaneous performances of melody. So within the framework of Birdsongs, we try and let the musicians do what they do best and give the shit work in the ensemble to the computer. Probably the next thing on the curve for us is developing pieces in which the computer will interact with us more in an attempt to break away from the sequencer / player model of interaction.

What form could this interaction take, and what degree of interaction is possible with today's technology?

KF: It's now possible to have the computer "listen" to (at least the MIDI part of) our performances, and react in some slightly intelligent way based on how we've programmed the computer. For example, it could listen for a particular melodic figure, and respond each time with a figure of its own, or an algorithmically-generated variation on the original figure.

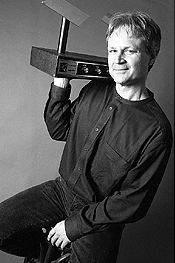

When I saw your concert in Atlanta back in March, Erik occasionally played what looked to be something like a MIDI theremin, or at least something that worked on the same principles. Is that what that was?

KF: It was a regular theremin. Erik is one of the few people who actually owns and performs on one these days, and he is (I think) quite good at it. I think his theremin is an original Maestro, but I could be wrong about that.

The performance and the recording aspects of the music each present different challenges and opportunities – do you enjoy one of those activities more so than the other?

KF: I think it is about even. They are very different, and we like them both!

So when the group is working out a new piece, how important and significant are the competing interests of a) creating something that can be faithfully reproduced by the four of you live, and b) creating something that takes full advantage of the various tools and opportunities a recording studio provides?

KF: Our main thrust has always been to do "a" when we are working out a new piece. Sometimes we end up doing "b" once we actually are in the process of recording a piece (we don't avoid doing things in the studio just because we wouldn't be able to do them live), but this is not how we approach pieces initially.

How often do you get to perform?

KF: Much less these days than before, due mostly to the fact that everyone has gotten so busy. We perform about once every other month, I'd say.

Are there any concert/tour plans in the near future?

KF: We'll be doing residencies / workshops / concerts in late September at Duke University (Durham, NC), and University of North Carolina at Ashville. Beyond that, nothing is firm, but we hope to do a West Coast / Hawaii tour in November of 1996.

Filed under: Interviews, Issue 8

Related artist(s): Birdsongs of the Mesozoic, Ken Field

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Review: Sterbus - Black and Gold

Published 2026-03-03 - Release: Janel Leppin's Ensemble Volcanic Ash - Pluto in Aquarius

Updated 2026-03-02 15:06:51 - Release: Janel Leppin - Slowly Melting

Updated 2026-03-02 15:05:27 - Release: Alister Spence - Always Ever

Updated 2026-03-02 15:04:11 - Release: Let Spin - I Am Alien

Updated 2026-03-02 15:02:41 - Review: Falter Bramnk - Vinyland Odyssee

Published 2026-03-02 - Review: Exit - Dove Va la Tua Strada?

Published 2026-03-01 - Review: Steve Tibbetts - Close

Published 2026-02-28 - Release: We Stood Like Kings - Pinocchio

Updated 2026-02-27 19:24:02 - Release: Stephen Grew - Pianoply

Updated 2026-02-27 19:20:11 - Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25