Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Reviews

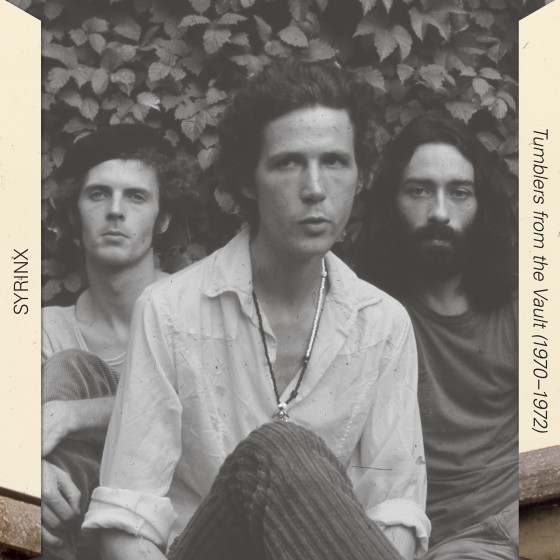

Syrinx — Tumblers from the Vault (1970-1972)

(RVNG Intl. ReRVNG08, 1972/2016, 2CD)

by Jon Davis, Published 2016-10-14

If anyone had any doubts that the late 60s and early 70s were a time of broad innovation and experimentation, this collection provides ample evidence that even outside the cultural centers of New York, London, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, musicians were creating new sounds. Syrinx was a Canadian group formed by keyboard player John Mills-Cockell, saxophonist Doug Pringle, and percussionist Alan Wells, and far from operating within the realm of psychedelic rock or jazz, they produced a wildly original blend of (then) cutting-edge electronics and avant-garde music. The closest comparison might be Silver Apples, though Syrinx is informed much more by classical chamber music than by rock or pop. After recording two albums, the members went their separate ways and their music faded into obscurity. With this collection, RVNG brings together all the previously released material along with some unreleased tracks. It starts off will all of the tracks from Long Lost Relatives, the group’s 1971 second album, followed by the self-titled debut from 1970; the second CD (third LP) contains all of the bonus material. The liner notes are extensive and informative, giving a thorough history of the music at hand.

Long Lost Relatives is the more consistently engaging of the original albums, so starting with it gets things off to a good start. For a modern listener coming to this music, many comparisons come to mind, frequently Cluster & Eno (1977), with its calm sense of melodicism. The percussion is often absent or quite understated, and functions more like orchestral percussion than anything else. “December’s Angel” is a lovely highlight, starting with a meditative Satie-esque keyboard and some electronic noises, then gradually adding a string section and a hint of Vivaldi crossed with Philip Glass. The saxophone comes in finally to emphasize the melody, bringing it to a beautiful close. Throughout the album, it’s clear that Mills-Cockell was not part of any of the electronic streams of the time: not using the synthesizers to imitate conventional instruments (as in Switched-On Bach), not abstract noises (along the lines of Forbidden Planet), and not simply sound effects added to more conventional music for a sense of exoticism or futurism (as in any number of recordings from the time). The music is consistently tonal and doesn’t venture much into dissonance, though many of the synthesizer parts are non-tonal or white-noisy, but the melodicism never comes off as simple-minded or nostalgic.

Syrinx, by contrast, has less in the way of instrumentation, relying on the core trio for all the sounds. Mills-Cockell plays piano, organ, and synthesizers; Pringle’s sax handles some of the melodies; and Wells sticks to gongs and hand percussion. This album started as a set of solo recordings by Mills-Cockell; the sax and percussion were added later, along with reworking some of the original recordings, but it all sounds natural enough that you wouldn’t know how it was created without reading the liner notes. Again, the music anticipates developments nearly ten years in its future. The compositions are deceptively simple, though they feature lush, complex harmonies and masterful use of texture. The sound quality is stellar, and without foreknowledge that it dates from 1969-70, a listener would never guess that it was anywhere near that old.

The highlight of the bonus material is the “Stringspace” suite, recorded live with a chamber orchestra. The four individual sections of the suite all appeared on the studio albums in different forms. This music was commissioned for the Toronto Repertory Ensemble and recorded for a television broadcast. It is testament to Mill-Cockell’s skills and studies in composition that the expanded versions work so well. Aside from the addition of the strings, Wells’ percussion gets a somewhat more prominent role in these versions, and Pringle’s sax work is more assertive. While the fidelity of these live tracks is not up to the standards of the studio albums, they are certainly listenable, and both a glimpse into another side of the band and a taste of what could have been if they had carried on. A particularly interesting bonus track is an alternate version of “Melina’s Torch,” which was the lead-off track of the debut album. There it was less than three minutes long, a pleasant tune with a few intertwining synthesizer parts, subtle bongos, and a sax melody that comes in halfway through. The “solo” version is (I think) the original Mills-Cockell tape. It is nearly ten minutes of fairly sparse synthesizer work, very interesting and experimental. Various bits of it were edited together, and the other musicians added their parts to create the album version. Perhaps less successful — but interesting nonetheless — is the vocal version of “Better Deaf and Dumb from the First,” which was an instrumental track on Long Lost Relatives.

All in all, this is an extraordinary collection, an important side-alley in the history of electronic music. Not only that, but it is eminently listenable, with artistic value in addition to its historical worth. RVNG has done this one right, providing an excellent package for music which deserves attention and respect.

Filed under: Archives, 2016 releases, 1972 recordings

Related artist(s): Syrinx

More info

http://rvng.bandcamp.com/album/tumblers-from-the-vault

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Release: Tashi Wada - What Is Not Strange?

Updated 2026-02-24 14:56:16 - Artist: Tashi Wada

Updated 2026-02-24 14:54:34 - Release: Greg Segal - Maintain!

Updated 2026-02-24 00:38:03 - Review: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Published 2026-02-24 - Review: Nektar - Mission to Mars & Fortyfied

Published 2026-02-23 - Review: Jaime Rosas - Tres Piezas de Rock Progresivo

Published 2026-02-22 - Release: Kevin Kastning & Bruno Råberg - Across Tall Rain

Updated 2026-02-21 00:42:08 - Review: Gary Husband - Postcards from the Past

Published 2026-02-21 - Release: Daniel Crommie - Februa

Updated 2026-02-20 14:23:17