Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

Seeking the Dimensional Connector —

The Kalaban Interview 2017

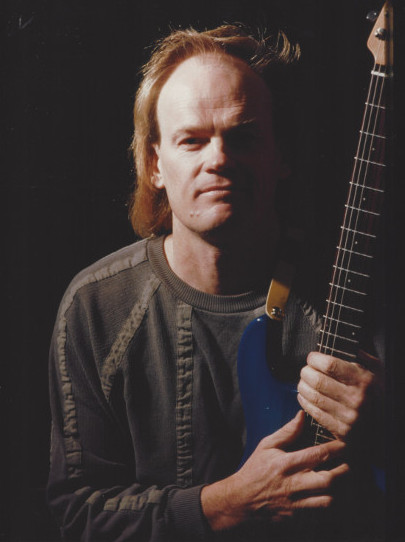

On the upper floor of a large garage on back side of the property, equipped better than most commercial garages might be, we walk up a long stairway and open a red door with something scrawled on it. This is Randy Graves’ world class recording studio, where he and drummer Kyle Nish have been working on the latest Kalaban release, Edge of Infinity. These days it’s more of a project than a working band. If there were a need to play live, musicians would have to be hired to play the various parts, but at this point Graves and Nish are content to simply create music in the studio and record it. Tonight is a special night, they are working on a long piece of music (as yet untitled) destined to be used as the soundtrack for a motor sport racing DVD, filmed on the Bonneville salt flats west of the Great Salt Lake.

by Peter Thelen, Published 2017-06-22

Where did Kalaban start?

Where did Kalaban start?

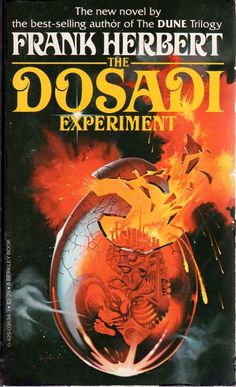

RG: Kalaban started way back in ’75. It came from the Frank Herbert book The Dosadi Experiment, and the kalaban was like a pan-dimensional creature, and like all galactic authorities it was subject to corruption, and so it was hired to maintain a god wall around a prison planet, but the interesting thing for my purposes was the idea that the kalaban could transport people through dimensions, and it could also be a connector from dimensions. So because of that it’s kind of like a universal translator, and since music is a universal language, I thought the idea of the Kalaban was pretty cool, using music to transcend languages and transcend cultural boundaries, that’s where Kalaban came from.

How old were you then?

RG: That was ’73, so I would have been 21. When I was 15 I wanted to be label-less, and I was totally into this kind of “I would rather be anybody besides myself,” so I hitch-hiked around the country a lot and showed up on peoples’ door steps, and they would ask “How did you get here?” I would say “I walked”. I walked the roads and rode in peoples’ cars, and a couple of those cars were state troopers’ back seats, but I got here. So that’s kind of where that all came from, and the whole idea of using music to communicate ideas that couldn’t be communicated via some common language other than music, that’s what I was thinking. A pretty simple idea but it had kind of a fun sort of genesis to it. Anyway, this is the third version of Kalaban. The first version was myself and Craig Parker, and I converted an ice cream factory into a studio, that was the first studio that I built.

What did Parker play?

RG: He played keyboards, and a little bit of guitar. I played a lot of guitar and a little bit of keyboards. We did a lot of really electronic stuff that didn’t have very much rhythm to it, but it was really a lot of fun, we had a lot of experience playing with synths because they were very new at that point, so you could do a lot of stuff that didn’t relate to people very well, and because it sounded fun, we recorded it anyway. Like one of the first songs we released was called “Soulthon Generation 13” and it was about a planet-sized computer, kind of along the lines of the Isaac Asimov Foundation series of things, where the whole planet was this big computer, and the idea was that the computer controlled the whole galaxy. But our recording methods were not very good. I had a friend who had just built a console for Barbra Streisand, he and I got together and built a console for that studio, and that console was way better than our ability to use it, We didn’t know what the heck we were doing. It took me a long time to figure out how to use this kind of gear. Then I went to school and got an EE degree and figured out that if I was going to be in electronic music, I was either going to pay someone else a lot of money to record something,or I was going to make my own studio. So this studio here, "Noise Floor Nine," is number seven.

RG: He played keyboards, and a little bit of guitar. I played a lot of guitar and a little bit of keyboards. We did a lot of really electronic stuff that didn’t have very much rhythm to it, but it was really a lot of fun, we had a lot of experience playing with synths because they were very new at that point, so you could do a lot of stuff that didn’t relate to people very well, and because it sounded fun, we recorded it anyway. Like one of the first songs we released was called “Soulthon Generation 13” and it was about a planet-sized computer, kind of along the lines of the Isaac Asimov Foundation series of things, where the whole planet was this big computer, and the idea was that the computer controlled the whole galaxy. But our recording methods were not very good. I had a friend who had just built a console for Barbra Streisand, he and I got together and built a console for that studio, and that console was way better than our ability to use it, We didn’t know what the heck we were doing. It took me a long time to figure out how to use this kind of gear. Then I went to school and got an EE degree and figured out that if I was going to be in electronic music, I was either going to pay someone else a lot of money to record something,or I was going to make my own studio. So this studio here, "Noise Floor Nine," is number seven.

And from there?

RG: Kalaban version one, we did a lot of shows in Utah. We did things like, we had whale music at the opening of our shows, from the Andre Kostalanetz album, then we would get done playing a song, and people would [slow clap] “I think they were good… what was that?” That lasted until about 1981, and around that time I decided there weren’t any other musicians in Utah that I could actually work with, but I was working at Herger Music in Provo, and Mike Stout came in, he was a student, and he started playing in the back room where the keyboards were – he started playing “Tarkus” and I thought here is somebody who actually knows something about real music. So I went back there and we started talking and I did some improv stuff on “Tarkus” with him, and he says “I have this song called ‘Fantasy Impromptu’, do you want to play on that?” and that turned into the first Kalaban version two song called “Procyon’s Demise.” And about halfway through that song he said “Can we bring my brother in?” I asked what does he play, and he said drums.

RG: Kalaban version one, we did a lot of shows in Utah. We did things like, we had whale music at the opening of our shows, from the Andre Kostalanetz album, then we would get done playing a song, and people would [slow clap] “I think they were good… what was that?” That lasted until about 1981, and around that time I decided there weren’t any other musicians in Utah that I could actually work with, but I was working at Herger Music in Provo, and Mike Stout came in, he was a student, and he started playing in the back room where the keyboards were – he started playing “Tarkus” and I thought here is somebody who actually knows something about real music. So I went back there and we started talking and I did some improv stuff on “Tarkus” with him, and he says “I have this song called ‘Fantasy Impromptu’, do you want to play on that?” and that turned into the first Kalaban version two song called “Procyon’s Demise.” And about halfway through that song he said “Can we bring my brother in?” I asked what does he play, and he said drums.

So in the back room of Herger’s we started rehearsing, after hours, and this guy Gary came down, he had seventeen cymbals in his kit, he was a total Neil Peart fan, and so when he would come down we would set him up in the back room and it would take three hours to get his drum kit set up, and that would be like 10:30 or 11 o’clock at night,and so we would play until about 4 o’clock in the morning – we couldn’t get started until around midnight because of all his drum stuff. So that kind of set the tone for the next twenty years of Kalaban shows. It would always be Gary would show up, we would have to wait several hours for the drums to get set up, and then we would never get a sound check because we were already an hour late to play. I can’t tell you how many shows we did with no sound check. At one of the last shows we did, he had three gongs, two tubular bell arrangements, wind chimes, a hybrid kit of Roland electronic drums, and his regular acoustic kit. We were playing this show at Utah Valley University, and we got done playing at midnight, and I had the chore of doing my guitar stuff and all of the PA equipment, I was done packing up about 2:30, I had to be at work the next morning at 8; I drove by UVU the next morning on my way to work and he was still packing his stuff up!

I don’t feel so bad now…

RG: An amazing drummer. But he carried a lot of baggage because of his kit, so we just had to deal with that. When we played at Progfest ’94, we didn’t get a soundcheck there either. Show after show after show, we would have to start not knowing what our sound was going to be like. But we played a lot of good shows, and that was fun. So Kalaban version two with Mike and Gary Stout lasted from ‘81 until ‘98. Around that time we got kicked out of our most recent practice room, which was a converted racquetball court that I had worked on. “Troubador” [from Turn to Flame] has a really complicated guitar section in it, and I had finished recording all that and Gary called and asked “Could you move this part of the guitar section three bars further out, because my drum part was intended to be three bars longer”, and I said “I just spent two months working on this guitar section, I’m not moving it. It is what it is and it works.” Then he said “Okay, then I guess I’m done.” And I said, “What do you mean done?” He said “I’ll send you an email.” So we got an email with seventeen words in it that said “I can’t work with you anymore,” and that was the end of Kalaban version two. So that actually started about a thirteen year dead period for me, because I had just started a software company, I had to put all my time into that. Then around 2007 I decided to just do everything myself, because no one else seemed to be willing to hang with me for decades at a time, I can’t really blame them I guess.

RG: An amazing drummer. But he carried a lot of baggage because of his kit, so we just had to deal with that. When we played at Progfest ’94, we didn’t get a soundcheck there either. Show after show after show, we would have to start not knowing what our sound was going to be like. But we played a lot of good shows, and that was fun. So Kalaban version two with Mike and Gary Stout lasted from ‘81 until ‘98. Around that time we got kicked out of our most recent practice room, which was a converted racquetball court that I had worked on. “Troubador” [from Turn to Flame] has a really complicated guitar section in it, and I had finished recording all that and Gary called and asked “Could you move this part of the guitar section three bars further out, because my drum part was intended to be three bars longer”, and I said “I just spent two months working on this guitar section, I’m not moving it. It is what it is and it works.” Then he said “Okay, then I guess I’m done.” And I said, “What do you mean done?” He said “I’ll send you an email.” So we got an email with seventeen words in it that said “I can’t work with you anymore,” and that was the end of Kalaban version two. So that actually started about a thirteen year dead period for me, because I had just started a software company, I had to put all my time into that. Then around 2007 I decided to just do everything myself, because no one else seemed to be willing to hang with me for decades at a time, I can’t really blame them I guess.

Did both of those guys leave at the same time?

Did both of those guys leave at the same time?

RG: Gary left first, and then Mike moved to Texas. So once that happened there was nobody else that I could collaborate with locally, so I didn’t do anything for quite a while. And then at one point I realized I had all this music happening in my head, I’m going to do have to do what I can with who I have, which was me. All the songs on the album you just heard [Edge of Infinity] I wrote, and I played all the parts except for the drums. You can tell, there’s not another keyboard player in there. I’m a keyboard player enough to write and compose things, but I’m not a keyboard player from the live performance perspective. I’ve been looking for a keyboard player for at least five years, and progressive rock keyboard players are not laying around on the sidewalk. I would love to have a keyboard player to collaborate with again.

After the breakup Mike and I formed a software company, and we told ourselves that it was going to be the kind of thing where we would sell our software, and then play our original music at night in clubs in the cities where we sold our software. We never played a single note in twelve years. The company just completely absorbed both of us, it got to the point where I realized I had essentially sold my soul to this company, and I had to get out of it. So I sold my part and got out of it.

How about Mike?

RG: Mike is still in Texas and he’s still doing the same kind of work. He took my shares, and ultimately sold them to another company, and now he’s an independent consultant. I actually tried to get him back into the music part of it, even though he was in Texas. I created places for him to play on some of the songs that are on Edge of Infinity, but he just wasn’t available. He was so busy doing this other stuff still. The thing that he said that really ended it, I had a sixteen bar section for him to do a piano piece in, and he was out of practice enough that he couldn’t really sync into it. I ended up writing the piano part. When I tried to get him to play the part that I had written, he got so frustrated he said, “Kill me now.” That’s when I realized his head wasn’t in the right place anymore. He’s doing his own thing, different paths, and we still talk here and there, but the relationship is nothing like it used to be. It’s too bad, because I think we had really good chemistry.

He may find it again someday…

He may find it again someday…

RG: Maybe, if he can get his head out of the business world. But he has a really good time, he’s really smart, and he likes working with people in the corporate world. He gets a certain amount of energy from that. Can’t argue with that, because it also pays really well.

So that’s kind of where things started up again in ’07. I was running my company out of this office here, and I decided not to put any walls up or hire any people, because I thought I may want to have this room to do something else, and then of course I built this control room out of it. So this latest album actually has songs that started as early as the mid-80s, I was fleshing out some stuff that’s been around for quite a long time. Now, this next album that Kyle and I are working on is the first one that has some brand new ideas in it. Not that there won’t be influence coming from the past, because that always happens too.

It’s inevitable there will be some.

RG: I had a motorcycle accident in 2009, I was going to be a programmer again, I was in school up at University of Utah, and after the motorcycle accident I thought I don’t even know if I’m going to live another two weeks. I’m going to do this music, and I’m going to keep doing this music until I can’t do anything. That’s when this latest album really got going. I ended up buying two of these consoles, and assembled all the pieces, rewired stuff and built one console out of two and sold the other stuff off, so this is the first studio that I would consider to be real professional quality. Edge of Infinity came together while I was building all of this stuff, it took a long time because there were a lot of things besides the music that had to happen, but now every thing's working, and the next one should be really focused on the music instead of getting everything else running too.

Kyle, where did you come into this picture?

KN: Around 2013. Going back to 2009, Gary, the previous drummer, had passed away. Randy and I, we had known each other for some time, I had been in the music business 30 years already, he would come up to our store in Centerville, I knew who he was, we had some mutual friends, and then I came down to Orem to work at Murdock Music, and he knew Dave [Murdock’s guitar tech] and we just struck up a conversation one day, Randy was looking for a small drum part on the “Opus” track that was in 15/8 time signature, and he wanted to know if I could record that on v-drums so he could just import the midi notes into the recording. So that kind of started the conversation. We talked about getting together and doing some recording. At the time I didn’t have any drums, I had taken about a 20 year break [from playing], getting married, having kids and running music stores, never had a place to set a drum kit up, so Randy came down and bought a drum kit, I bought a bunch of more pieces, and we started doing stuff, it’s been four years now working on this project. It’s been an incredible amount of fun. I decided a long time ago, one day I’ll get to play again, but I don’t really want to play in clubs anymore, I wanted to do the kind of music I like to play.

KN: Around 2013. Going back to 2009, Gary, the previous drummer, had passed away. Randy and I, we had known each other for some time, I had been in the music business 30 years already, he would come up to our store in Centerville, I knew who he was, we had some mutual friends, and then I came down to Orem to work at Murdock Music, and he knew Dave [Murdock’s guitar tech] and we just struck up a conversation one day, Randy was looking for a small drum part on the “Opus” track that was in 15/8 time signature, and he wanted to know if I could record that on v-drums so he could just import the midi notes into the recording. So that kind of started the conversation. We talked about getting together and doing some recording. At the time I didn’t have any drums, I had taken about a 20 year break [from playing], getting married, having kids and running music stores, never had a place to set a drum kit up, so Randy came down and bought a drum kit, I bought a bunch of more pieces, and we started doing stuff, it’s been four years now working on this project. It’s been an incredible amount of fun. I decided a long time ago, one day I’ll get to play again, but I don’t really want to play in clubs anymore, I wanted to do the kind of music I like to play.

RG: I think it was kind of interesting that the first thing I threw at him was a 15/8 section. I had put together a very simple part, if you can call anything that’s 15/8 simple, but I just didn’t want to spend my time programming drums; I would rather write more music and get someone who could actually contribute, and so I gave him this one section and he did a great job on it. I thought: Have I found someone who can actually deal with this sort of music? So we started talking more and more, and like he said, I came into the store and bought a drum kit, and truth be told the number one reason why I bought the drum kit was to see if I could convince him to come play here. And it worked! (laughs)

KN: The more we talked bout stuff, the more we realized we like the same kind of music. We are both tremendous Rush fans, that just kind of cemented the relationship as far as that goes.

RG: I think the other piece of it was that I wasn’t asking him to be part of a bar band. I’ve played bars here and there, but it’s never really been that much fun for me, because the music that you need to play in bars is just not that much fun. It’s probably a lot of fun for the people that are dancing, but certainly not for me as a player, and so the fact that I was talking to Kyle about playing original music and recording it and getting published, and doing something that would actually be challenging, I think that’s what really pulled him in.

Agreed. Original music is where it’s at!

Agreed. Original music is where it’s at!

RG: There’s nothing wrong with being a cover band, it just depends what you want to do. If you want to be a cover band, more power to you, but the idea of playing for an audience that’s really zoned in on what your mind came up with, that’s a completely different layer. For example, at Progfest 94 in the middle of “Hotash Slay” there were a couple of sections where the entire audience came out of their seats in the middle of the song, and just started screaming, and the energy that the audience gave to me was pretty much better than anything I’ve ever felt. There was like this energy loop between me and the audience. That’s happened a few times when we were playing our original stuff, but I’ve never felt anything like that playing a cover tune. As a composer, and as a performer, that’s like the ultimate – the audience just goes yeah, we’re in it with you. To have that, I don’t know any other way to ge there other than doing original music. Those memories stick with you.

Kyle, what kind of bands had you played in before this?

KN: When I was a kid I went through school jazz bands, when I was in high school I started working at Guitar City up in Centerville, and I had met through a mutual friend a guy named Paul Richards, who is in the California Guitar Trio now. He actually came and worked at Guitar City for a while, we were both in high school at the time. We would work together, then we got together with a couple other friends, we would jam out to Rush songs and other songs. Then I had a couple other buddies from high school, we would play cover tunes in a band. I was in three or four of those cover bands, we would do school dances and stuff like that. In the early 90s I was in a couple other bands and we were doing clubs, a mix of country and classic rock. Then around 1993 or so, I just took a break, and that break ended up lasting twenty years!

When the full band was going and you were performing, were there receptive venues in Utah?

When the full band was going and you were performing, were there receptive venues in Utah?

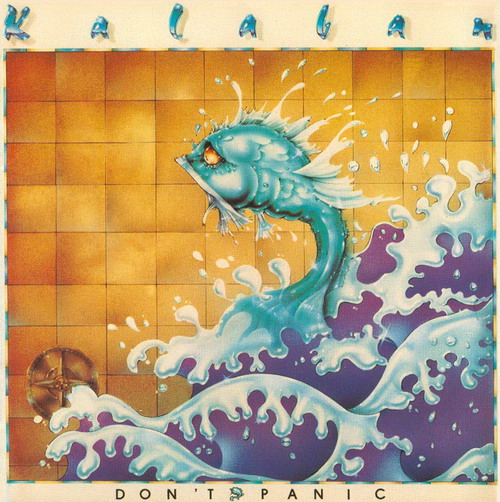

RG: The Zephyr Club, which is no longer, was one of the great venues in Utah. We opened there for Kansas and for the Dregs, and we had absolutely great reception, the energy in the room… it was electric. Utah is not a great place for progressive music… America is not that great, and Utah is probably on the lower end of that, but they are out there. And one of my big failings is that I’ve never put the effort into getting it out there. It’s always been so much more fun for me to make the music than to promote the music, I always let the promotion happen or not, as the case may be. That’s just one of my own failings. We got fan mail from all over the world, I probably have ten bushels worth of letters. The market is out there, the people are out there, and when we were first doing this, when we put out Don’t Panic and Resistance Is Useless, the internet was nothing like what it is now, so we didn’t get anywhere near the exposure that would have helped us out.

Agreed, the internet was just in its infancy then…

RG: This new album, I’ve had… like the guy who designed this console, Tom Graese, he got a hold of some of my music and he sent me five emails in one afternoon. He said “I can’t believe this stuff, this is awesome, this is great,” and he’s been passing it around to all his friends in South Florida, so I now have studio owners asking “How do I get this music?” It just reminds me that this is pretty good stuff, maybe I should put a little more effort into getting it out there.

It makes you feel good though…

It makes you feel good though…

RG: Yes it does, the validation is huge. I mean this guy engineered for Pink Floyd and King Crimson, and he’s telling me “This is Crimsonesque, I really like this.” So it’s like after twenty years of not doing anything you finally put out another album, and all of a sudden people that have some real ears are saying they like this, and then they share it with more of their friends. So in the last week I’ve heard from five studio owners, they ask, “Where have you been, what have you been doing?”

KN: On the other side of that coin for me, this is the first time I’ve ever done anything like this. Started playing drums when I was nine years old in ’73. My parents saw it in me, and said we better get this boy some drums before he starts destroying property. So I played drums, I went through school, I taught myself pretty much. I don’t read music very well. I listened to Buddy Rich until I couldn’t hear anymore. Then in high school I got turned on to Neil Peart, and then the gates kind of closed. Buddy Rich and Neil Peart and that’s pretty much all I cared about for a long long time. Then later on in the 80s I started to listen to other kinds of stuff, more jazz and fusion when I worked at a radio station in Ogden for a while, which kind of opened my eyes a bit. Randy turned me on to so much cool stuff from the past, but never have I done anything to this degree, and it’s quite satisfying.

RG: So I guess that brings us to the most recent album. The whole idea of the ‘edge of infinity’ is when the land comes to the ocean, all the tide pools and all the cool interesting stuff happens at that edge. It got me thinking about the fact that th really cool stuff in life seems to happen at the edges of things. You might be crossing the Sahara desert for weeks and weeks, and when you come to an oasis, that’s an edge. You might be in a relationship for years and years, that relationship might end and a new relationship starts, that’s another edge. The transition from one thing to another is where the real drama and interest occurs.

And so “Berlin” is about the idea of a relationship ending, “Opus” is about the edge of one social system ending and another one starting, because the bankers are killing things. “God Is an Avon Lady” is about the idea that the universe is knocking at our door to get us to answer the call to wake up and become a bigger part of the universe, and that’s an edge, from one layer of consciousness to another.

And so “Berlin” is about the idea of a relationship ending, “Opus” is about the edge of one social system ending and another one starting, because the bankers are killing things. “God Is an Avon Lady” is about the idea that the universe is knocking at our door to get us to answer the call to wake up and become a bigger part of the universe, and that’s an edge, from one layer of consciousness to another.

All these songs are about the drama that occurs at some kind of edge, one system of feeling or being or thinking, to another one. All these songs are about pictures, there’s a story, and I have a movie that goes on in my head. I like movie soundtracks a lot, but I would really like them to be more rock oriented. “Jade Eyes” is another edge song, about the time I was getting ready ready to be divorced there was a girl by the name of Matise, I happened to meet her – not the first time – in a grocery store parking lot, and as she was walking toward me, the sun was behind her, she had this big beautiful blond hairdo, the sun was kind of shining through her clothes, and she had this kind of angelic thing going, and I thought that was pretty amazing. Nothing ever happened with her, but that image was pretty potent for me, and so I wrote that song,and I was thinking about the Hendrix song ”One Rainy Wish,” if you think about it while you listen to that song, you can see where it came from. It’s not really a progressive song as such, more like an acid rock 60s sort of dream song.

Between The Beatles and Yes and Rush, those three bands are what I would consider my top of the list. Songs that do a really good job of telling a story. Girl meets boy, boy meets girl, boy loses girl… those are pretty common themes in songs. The cool thing about progressive music are that the songs are not just about that. I was at a Yes concert around twelve years ago on their 35th anniversary tour over in Denver at Red Rock [Amphitheater], they were playing “South Side of the Sky,” at that time there was a lot of fog, a lot of clouds, and I was out there in the rain, and you could see planes taking off from Denver International, and they were going up into the clouds, they had all their lights on, and they were singing about… “Were we ever colder on that day,” it felt like those planes were taking people off the planet to escape to some other dimension. This is one of those things where Yes’ music contributes to a kind of other worldly experience. It seems like every show I’ve been to of Yes has had at least some of that, it’s got that ability to transport you to somewhere else.

That’s what I go for in music, I want it to take you somewhere and leave you in a different place. All of my music teachers I’ve ever had, they want you to compose something that brings you back to the home plate at the end of the piece, and I kept telling them I didn’t want that, I wanted listeners to be somewhere else when they were done listening to it. One of the best compliments I’ve had was from Tom Graefe, (the designer and lead engineer of my Sony recording console), when he got done listening to “Opus Octopus” he emailed me and said ‘what a journey.’ (He actually emailed me 5 times while listening to the album…)

It’s long… (laughs all around)

KN: It should be in the liner notes. Pack a lunch when you listen to “Opus,” it may be long but it does take you on a journey, you don’t end up where you started, that’s for sure.

Filed under: Interviews

Related artist(s): Kalaban

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Review: Leon Alvarado - The Wicked Forest

Published 2026-03-12 - Release: Kevin Kastning / Paul Wertico - Interchange One

Updated 2026-03-11 15:17:43 - Artist: Paul Wertico

Updated 2026-03-11 15:16:01 - Release: Alan Jenkins - Pig Costume from the Time of the Vikings

Updated 2026-03-11 15:10:33 - Release: Bruce Soord - Ghosts in the Park

Updated 2026-03-11 15:08:52 - Review: Erik Wøllo - Snow Tides

Published 2026-03-11 - Review: Sigmund Freud - Risveglio

Published 2026-03-10 - Release: Schrödingers Katze - The Cat Is Alive

Updated 2026-03-09 23:58:35 - Release: Schrödingers Katze - Unscharf

Updated 2026-03-09 23:55:37 - Release: Schrödingers Katze - Superposition

Updated 2026-03-09 23:53:29 - Artist: Schrödingers Katze

Updated 2026-03-09 23:41:21 - Review: John Greaves - Chanson d'Automne

Published 2026-03-09 - Release: Corima - Humab Ku

Updated 2026-03-08 14:32:07 - Review: Jérémie Ternoy Trio - Survol a Basse Altitude

Published 2026-03-08 - Review: Runaway Totem Feat. AndromacA - Metaphorm Tetraphirm

Published 2026-03-07 - Release: Jeff Aug - Interim

Updated 2026-03-06 17:20:22 - Release: Taupe - Waxing / Waning

Updated 2026-03-06 15:43:53 - Release: Taupe - Not Blue Light

Updated 2026-03-06 15:42:29 - Release: Taupe - Fill Up Your Lungs and Bellow

Updated 2026-03-06 15:41:33 - Artist: Taupe

Updated 2026-03-06 15:39:51