Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

Of Velcro Ears and Eccentric Geniuses —

C.W. Vrtacek / Forever Einstein Interview

It was every guitarist’s worst nightmare. A freak accident with a table saw had just severed the first digit of Chuck Vrtacek’s index finger on his fretboard hand. Instead of freaking out he calmly called the paramedics, and 15 minutes later was joking with them on his way to an operation at the hospital. Instead of perceiving the accident as a huge setback, he saw it as a challenge, and he immediately went home and started playing with his second, third, and fourth fingers. Instead of canceling his upcoming recording session he went into the studio with his band Forever Einstein and recorded their most ambitious and adventurous album to date, Down with Gravity.

by David Ashcraft, Published 2003-08-01

Charles W. Vrtacek is no ordinary person, and Forever Einstein is no ordinary band. The instrumental trio incorporates influences ranging from surf guitar, spaghetti western soundtracks, Middle Eastern and oriental scales, a Zappa-esqe sense of humor, and a jazzy chordal approach into a seamless and highly coherent sound. The band focuses on ensemble work with tightly composed, multi-themed tunes that have a tremendous melodic sense. The music is remarkably accessible considering the intricate compositions. As a result Forever Einstein appeals to both the “progressive” crowd as well as a much broader audience. The only problem is that many people have never heard their music. The typical reaction of live audiences is “You guys are great! Why haven’t I ever heard of you?”

Charles W. Vrtacek is no ordinary person, and Forever Einstein is no ordinary band. The instrumental trio incorporates influences ranging from surf guitar, spaghetti western soundtracks, Middle Eastern and oriental scales, a Zappa-esqe sense of humor, and a jazzy chordal approach into a seamless and highly coherent sound. The band focuses on ensemble work with tightly composed, multi-themed tunes that have a tremendous melodic sense. The music is remarkably accessible considering the intricate compositions. As a result Forever Einstein appeals to both the “progressive” crowd as well as a much broader audience. The only problem is that many people have never heard their music. The typical reaction of live audiences is “You guys are great! Why haven’t I ever heard of you?”

Some History

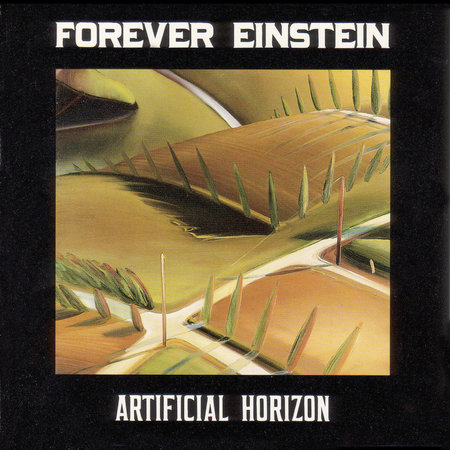

Guitarist Chuck Vrtacek and drummer extraordinaire John Roulat started playing together in 1980 after an introduction from Nick Didkovsky (later of Dr. Nerve). Chuck and John formed an instrumental quartet called Dancing Lessons that eventually morphed into Forever Einstein several years later. The first two Einstein albums, Artificial Horizon and Opportunity Crosses the Bridge featured a large number of extremely short (one to two minutes) pieces that were absolutely bursting with ideas. At times the brevity of the pieces didn’t always allow for thematic development, but overall the effect was impressive and unique. The albums received very favorable press from critics around the globe, and an astute review in Rolling Stone described the band’s sound as “Imagine the Minutemen playing Henry Cow charts.” Despite the incredible potential displayed on the first two albums, Forever Einstein was only hinting at what was to come.

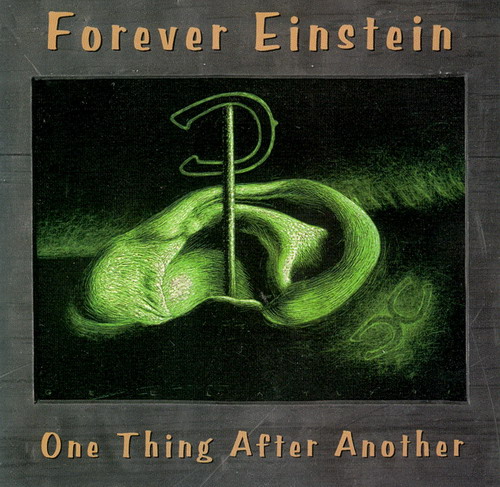

The band came to a grinding halt as John Roulat moved to Switzerland for three years, and Vrtacek realized that there was no Forever Einstein without his amazing drummer. Naturally when Roulat returned to the States the band reformed, and they entered a highly creative and fertile period. With Yale professor Jack Vees joining on bass the band recorded Vrtacek’s increasingly complex and mature compositions. The result was a quantum leap, and 1998’s One Thing After Another was the spectacular outcome. The album fully realized the band’s potential with three true lead instruments and an expansion of the tunes from 29 shorter pieces on the previous album to only 11. The album features a remarkable consistency of compositions so that there are truly no weak cuts. “Down With Gravity” followed two years later in a similar vein but with two experimental tracks, one of which had the band pushing the envelope on a nearly twenty-minute piece with plenty of improvisation.

The Faces of Einstein

The band’s music is all about compositions and instrumental interplay rather than flashy solos. Having said that, each of the instrumentalists has a unique voice and serious chops. The difference is that they put the tunes first rather than their egos. Roulat is a very unusual drummer, and his style is to accentuate the melody rather than merely keeping time. His array of sounds includes woodblocks, cowbells, rimshots, a bicycle bell, and even a rubber ducky squeeze toy that he incorporates in a solo! He is a very intuitive drummer whose intelligent and whimsical style fits the band perfectly. Jack Vees’ playing on the third and fourth albums provided a lead bass approach, and he often would provide counterpoint melodies. Einstein’s new bassist (their third) is Kevin Gerety whose fretless playing will be heard on their upcoming release, Racket Science. Besides functioning as the primary composer for the band, Chuck Vrtacek is a remarkable guitarist. This is often overlooked as critics tend to focus on his compositional ability, but his mastery of multiple musical styles is what defines the band. While he is frequently picking out clean lines with arpeggios, playing jazzy chords, or plucking twangy melodies, Vrtacek can also turn up the heat. His wild heavy metal leads on the opening track of “One Thing After Another” are dedicated to his pal Nick Didkovsky, and they prove that Vrtacek can be a great soloist in a wide variety of styles.

Cultural Pirates?

Forever Einstein incorporates a remarkable range of musical ideas and idioms that somehow are effortlessly distilled into an identifiable sound. As Vrtacek states in the liner notes to Down with Gravity, “Despite Einstein’s many influences, we are not merely impudent cultural pirates combining a variety of styles in order to prove our cleverness or show off our knowledge of popular culture”. He goes on to explain later: “Our ears are made of Velcro and everything sticks”. The result is a quirky and unique sound that is remarkably accessible despite the compositional intricacy. The typical Einstein piece (if there is such an animal) features multiple melodic themes weaving in and out that tie the music together without ever getting repetitious. The tongue in cheek humor pervades both musically and in the song titles (an example: “A fruit pie salesman with a whoopee cushion living in Wichita Falls OR Wow! If your fly wasn’t open you’d look just like Roger Moore”). In a way the music works like the better cartoons (such as Simpsons/Rugrats/Rocky & Bullwinkle) in that it functions on multiple levels. Just as the humor in the cartoons works for both kids and adults, Einstein’s music is melodic and approachable but also has the complexity to appeal to the progressive crowd. One really has to hear the music to appreciate this dichotomy.

Forever Einstein incorporates a remarkable range of musical ideas and idioms that somehow are effortlessly distilled into an identifiable sound. As Vrtacek states in the liner notes to Down with Gravity, “Despite Einstein’s many influences, we are not merely impudent cultural pirates combining a variety of styles in order to prove our cleverness or show off our knowledge of popular culture”. He goes on to explain later: “Our ears are made of Velcro and everything sticks”. The result is a quirky and unique sound that is remarkably accessible despite the compositional intricacy. The typical Einstein piece (if there is such an animal) features multiple melodic themes weaving in and out that tie the music together without ever getting repetitious. The tongue in cheek humor pervades both musically and in the song titles (an example: “A fruit pie salesman with a whoopee cushion living in Wichita Falls OR Wow! If your fly wasn’t open you’d look just like Roger Moore”). In a way the music works like the better cartoons (such as Simpsons/Rugrats/Rocky & Bullwinkle) in that it functions on multiple levels. Just as the humor in the cartoons works for both kids and adults, Einstein’s music is melodic and approachable but also has the complexity to appeal to the progressive crowd. One really has to hear the music to appreciate this dichotomy.

A Chat with Chuck

It’s not difficult to get Chuck Vrtacek to talk. He is happy to share his opinions on a variety of topics, and you can find out more about him and his thoughts on the various Einstein and Vrtacek websites that exist. Expose had the opportunity to ask him a few questions, and Chuck was off and running. Here are some excerpts…

How would you describe the music of Forever Einstein? What are some of the influences that show up in the music?

Instrumental rock music, plain and simple. When I was growing up in the 60s rock music was encouraged to evolve, it was expected. So the Beatles went from “She Loves You” to “Tomorrow Never Knows,” and Dylan went from an acoustic folkie to an electric stoner poet and the Byrds went from folk-pop to create the first country rock album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and so on. That’s why Miles Davis ended up hanging with rock musicians – he didn’t want to stand on stage in a suit and tie and play straight ahead jazz, so rock audiences welcomed him. If rock had continued in this vein instead of becoming economically driven and musically retarded, Forever Einstein would just be part of the rock world and accepted as such. But rock music regressed – after disco in the mid 70s, the bands that brought rock music back to the commercial forefront were Fleetwood Mac, Journey, the Eagles, BTO, Styx – I mean, come on!

I don’t like listing bands or styles as reference points because it’s not accurate for us, we blend styles too well, too seamlessly. If I say we have surf influences and influences from King Crimson, then the Crimson fans come to us expecting to hear some variation of their favorite Crimson song, same with surf fans or jazz fans or whatever. I hate – really hate – listening to musicians describing themselves as “eclectic” and “uncategorizeable” because Forever Einstein truly is and most bands can’t touch us for that. Even Steve at Cuneiform said to me “Chuck, nobody sounds like you guys.” That’s not a brag, it’s just a fact. Who sounds like us?

Who are the top two or three influences on your playing?

Top two or three influences? Impossible to answer for two reasons. First, I have two types of influences, those that influence my playing and those that influence my aesthetics. John Lennon and John Lydon / Rotten are examples of the latter but not the former. Jeff Beck is an example of the former but not the latter – he’s no John Lennon! One of my biggest influences is a guy named Bernie Moore. He had played and recorded with Johnny Smith (who wrote “Walk, Don’t Run”) in the 50s and he was a very good mainstream jazz player. One day he said to me, “If you stay in touch with the thing that made you want to play in the first place, you’ll never go wrong.” That has been a huge influence on me and it helped me through my accident. The other reason I can’t answer that question simply is that I’ve been playing for 41 years. The influences I had in 1968 are gone, and in ’68 I’d already been playing five years. Early on, my biggest influences were Richard Thompson, Rory Gallagher, Bert Jansch, and John Cippolina. Now and later, Joe Pass and Kenny Burrell. But Irish music is the key. People think my fast, clean arpeggiated picking comes from Bob Fripp and it doesn't. I learned to play Irish dance music on the mandolin at age 15 and that is where my propensity for playing quick arpeggiated, staccato runs comes from: jigs and reels. I’m Irish, by the way, though I didn’t find that out until recently because I was adopted and had to go searching, but it’s in my blood because I learned all this stuff a long time before I knew I was Irish. But I’m Irish and to prove it I’ll punch anybody who says I’m not!

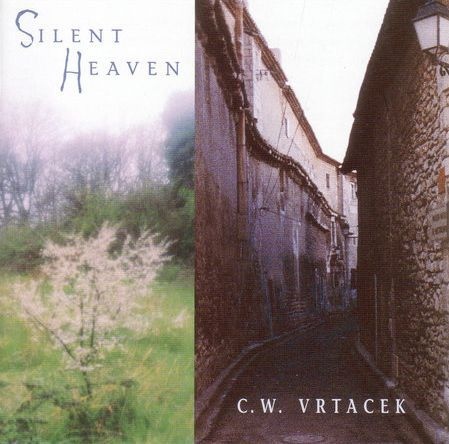

How would you compare and contrast Forever Einstein with your solo material?

Two completely different things, 180 degrees apart and each tied to a part of who I am. In public I am loud and talkative and sometimes pushy and abrasive and that comes out in Forever Einstein; privately, I am very quiet, don’t feel a great need to socialize and don’t turn on the TV or stereo. Consequently my solo albums are quiet, reflective, meditative, more involved with sonic exploration and pure melody and mood. The immediate reference points here are early Eno, Gavin Bryars, Satie, Debussy, and Mnemonists / Biota (I have become a regular contributor to Biota over the past few albums; Bill Sharp says I’m a member but I don’t think I deserve that title, they do more work than I do).

Two completely different things, 180 degrees apart and each tied to a part of who I am. In public I am loud and talkative and sometimes pushy and abrasive and that comes out in Forever Einstein; privately, I am very quiet, don’t feel a great need to socialize and don’t turn on the TV or stereo. Consequently my solo albums are quiet, reflective, meditative, more involved with sonic exploration and pure melody and mood. The immediate reference points here are early Eno, Gavin Bryars, Satie, Debussy, and Mnemonists / Biota (I have become a regular contributor to Biota over the past few albums; Bill Sharp says I’m a member but I don’t think I deserve that title, they do more work than I do).

Compare the four Forever Einstein albums and tell us what to expect regarding the one in progress now.

I think of the second album as an extension of the first one and the fourth album an extension of the third one. They would make very logical 2CD sets because the second and fourth CDs simply expand on ideas and territory staked out on their immediate predecessors. I think the differences between CDs 1 & 2 and CDs 3 & 4 are fairly obvious: the first two albums were characterized by a freneticism that disappeared on later albums, lots of very short, high-speed songs. We were hell bent on putting as many ideas as we could into a two-minute composition. The last two CDs moved away from that with longer compositions and soloing and got us reviewed in Relix and got us some fans in the “jam band” area. I’ve been told – only told – that guys from bands like Gov't Mule and some other bands like that are Einstein fans. The next CD which will be called Racket Science should occupy a space between those versions of Einstein. There will be very short pieces on the new album and longer ones, loud ones and quiet ones. I tried very hard when I wrote the music for the next CD to not throw the baby out with the bath water, you know? I tried to look at all four CDs and say ‘What did we do well, what are our strengths, what parts are weak?’ and then write music that takes that into consideration. There are a lot of shamelessly catchy melodies but I think they are subverted and contrasted with enough so-called “progressive” or “experimental” ideas to keep people on their toes. When John heard the new material he said, ‘Wow, this is really normal but it’s not, it’s still very Einsteinian if you dig into it.’ Or to keep peoples’ ears on their toes.

Cuneiform Records has been wonderfully supportive of creative music. How did the band come to Steve Feigenbaum’s attention?

In the early 80s I put out a couple of solo albums on my own label, which meant I had them piled up in my house and I contacted distributors, shipped them, collected the money owed, etc. Steve carried my albums before Cuneiform was created and we became friends through our business relationship. He happened to be in Providence, Rhode Island at one of our early gigs so he came by and signed us on the spot. At that point I had known Steve for probably ten years. Steve, by the way, is unique. He’s honest, interested, dedicated, funny, smart, and has integrity.

You and John are the core of the band. Describe his unique style.

John and I have been working together since 1980 and we often refer to each other as the brother we never had. We are best friends and our families socialize with each other. We’ve had times where we really got on each other’s nerves but obviously we worked through it.

John’s style is Forever Einstein, if you ask me. When he moved to Switzerland for a few years, I tried everything I could think of to keep the band going without him and I couldn’t – no John, no Einstein. What’s unique about John are his influences and how he deploys them. He’s a drum collector and knows vintage drums. He is a very musical drummer and can whistle every guitar and bass part pitch perfect. He has great rudiments and chops and can play any time signature, two time signatures simultaneously, fast flashy stuff, whatever – fusion, metal, reggae, etc. Now, given all that, he could have just gone in one direction and been a world class drummer doing one thing but what he likes to do and what he does best is mix all this stuff together at once and he loves throwing in humorous, silly bits. So he could easily play with King Crimson, he’s as good as Bruford, but he’d probably piss off Bob Fripp by occasionally throwing in something silly or odd or unexpected without warning, purely for his own enjoyment.

John’s style is Forever Einstein, if you ask me. When he moved to Switzerland for a few years, I tried everything I could think of to keep the band going without him and I couldn’t – no John, no Einstein. What’s unique about John are his influences and how he deploys them. He’s a drum collector and knows vintage drums. He is a very musical drummer and can whistle every guitar and bass part pitch perfect. He has great rudiments and chops and can play any time signature, two time signatures simultaneously, fast flashy stuff, whatever – fusion, metal, reggae, etc. Now, given all that, he could have just gone in one direction and been a world class drummer doing one thing but what he likes to do and what he does best is mix all this stuff together at once and he loves throwing in humorous, silly bits. So he could easily play with King Crimson, he’s as good as Bruford, but he’d probably piss off Bob Fripp by occasionally throwing in something silly or odd or unexpected without warning, purely for his own enjoyment.

Moving On

With the new album in the works and an upcoming performance at the Progday festival in September, Forever Einstein continues to move forward. Vrtacek views his accident as the motivation that has caused him to delve deeper into guitar history, collecting, and modification as well as more jazz, scales, and theory. As he puts it: “Had it not happened I probably would have taken the lazy route and kept playing the way I always played for the rest of my life.” With his track record it is highly unlikely that Vrtacek would have treaded water musically. As he states: “I see my music as a spiritual enterprise, even Einstein, not just my meditative solo stuff. Because you can see what commercial culture does to music. You have to be true to yourself and keep the music in a pure place…”

Clearly Vrtacek and his compatriots in Forever Einstein have succeeded in their goal of creating a unique and highly enjoyable brand of music without selling out at all. The irony is that their music has the ability to appeal to a wide variety of listeners, but until more people have the opportunity to hear the band, Einstein will continue to toil in relative obscurity. Once people do give them a listen they will learn what music critics from all over the world have know for years: Forever Einstein is a great band that is extremely fun to listen to. Perhaps it’s time to check them out and see for yourself…

Filed under: Profiles, Interviews, Issue 27

Related artist(s): Forever Einstein, C.W. Vrtacek (Charles O'Meara)

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Release: Tashi Wada - What Is Not Strange?

Updated 2026-02-24 14:56:16 - Artist: Tashi Wada

Updated 2026-02-24 14:54:34 - Release: Greg Segal - Maintain!

Updated 2026-02-24 00:38:03 - Review: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Published 2026-02-24 - Review: Nektar - Mission to Mars & Fortyfied

Published 2026-02-23 - Review: Jaime Rosas - Tres Piezas de Rock Progresivo

Published 2026-02-22 - Release: Kevin Kastning & Bruno Råberg - Across Tall Rain

Updated 2026-02-21 00:42:08 - Review: Gary Husband - Postcards from the Past

Published 2026-02-21 - Release: Daniel Crommie - Februa

Updated 2026-02-20 14:23:17