Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

Of Lions and Salads —

The Miriodor Interview 2014

The scene: Sunday dinner break at a loud and busy cafe a few doors down from the Columbia City Theater in Seattle. The previous night Miriodor had given an outstanding headlining performance on the first night of the second Seaprog festival. The whole band was on hand to reflect on that performance, and the 35 years on from their humble beginnings in Quebec City.

by Jeff Melton, Published 2015-02-18

photography by Danette Davis

PG = Pascal Globensky (keyboards, acoustic guitar)

RL = Rémi Leclerc (drums)

BF = Bernard Falaise (electric guitar, bass)

NL = Nicolas Lessard (bass guitar, keyboards)

So, Pascal, the band’s been together for over thirty years, correct?

So, Pascal, the band’s been together for over thirty years, correct?

PG: Thirty-five years.

What was the original concept/idea of the band when you formed it with Rémi?

PG: Well, of course at that time we were quite young and had a lot of influences. Actually, here’s Rémi. So, Rémi and I were listening to a lot of progressive music, Pink Floyd, Gentle Giant, Van der Graaf, Genesis, Yes, King Crimson and so on, so the idea was just to really, to learn music, and try to do something similar to them. Obviously, in those years the influences were kind of obvious, or more obvious, than they are today, but we were willing, foolishly, to try to emulate these bands.

What was the music scene like in Quebec City? Was it supportive of progressive rock? Or was it something that’s very common, or did you have to go dig it up, just to be able to hear what you wanted to hear?

RL: The scene in Quebec City was stimulating. In those days there were a lot of progressive bands, very popular, and bands from Quebec also, like Maneige, Harmonium, Sloche.

And you’ve seen these bands live, some of them?

RL: Yes, some of them. Like Maneige. Very good. Very stimulating. So, yeah, it was a good, open period, open for musical expression. Even on the radio I heard Gentle Giant, and King Crimson.

How did you two meet?

How did you two meet?

PG: By the co-founder of the band, François Émond, violin player, sax player, he plays everything, I started the band with him and at one point we did some stuff only as a duo, and then we progressed as a trio, François Émond, Rémi and myself, and there was another member, he was with us for about one year, his name is Paul Dussault. At one time we were a quartet: myself, François Émond, Paul Dussault, and Rémi Leclerc, and eventually Paul and François quit the band later on.

The music early on when you first started was different, because the band went through obviously quite a few changes before you recorded the first record with the trio, right?

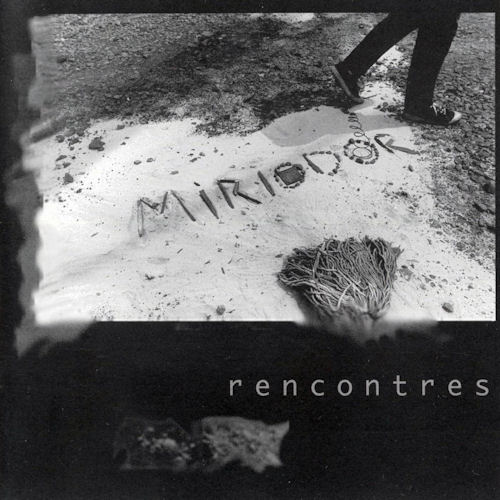

RL: Oh, yes, a lot. Rencontres was the closest to the beginning of the band. Rencontres is a younger expression.

PG: Yeah, with a lot of influences.

How did you know — you’ve obviously got songs that you’re writing, and trying out different things — how did you really decide the identity of the band, what Miriodor was going to be? When did you figure out that you really had something that was unique? Because it takes time, not only just playing, but rehearsing...

PG: It happened by itself. We were lucky. I don’t know how it happened, but we were lucky. Obviously on the first record there were a lot of influences, but quite rapidly we moved away from them, and I think we got our signature quite early in the history of the band, but I cannot explain how it happened.

RL: At the beginning it was already compositions and an artistic will to make something different.

PG: Quite early in the band we were quick to pinpoint influences in our music, so if someone would bring something that would mean maybe a hint of Yes or Genesis, we would say no, we don’t keep that, because it’s too much [like them].

Because you weren’t copying the influences, you were copying the approach, which is different.

PG: Yeah, we are always influenced by something but...

Did you have a vocalist, a singer?

Did you have a vocalist, a singer?

RL: Denis Robitaille, in the beginning, did some singing.

PG: One or two. Jongleries Élastiques (Elastic Juggling) has one piece with a Bulgarian singer.

Ah, really? Wow, that’s interesting.

PG: No lyrics, only...

Throat singing?

PG: Not throat singing, Bulgarian singing, but no words. Singing improv.

RL: I was working with a theater project, Compagnie Carbone 14, and she (Stefka Lordanova) was singing in the show, and we asked her to join us for one song. There are two pieces on Rencontres with vocals.

PG: Largely influenced by Van der Graff, Peter Hammill of Van der Graff. we opened for them in Quebec City a few years ago in 2008? No, 2009. it was an honor for us.

Tell us about your recording sessions for Cobra Fakir. Obviously, the writing now is taking off...

PG: We have Bernard [Falaise] and Nicolas [Lessard] in the band now. For a few years...

Yes, but the fact is the guitar is such a strong element of the band now, and I’m very interested in how it's working, particularly what kind of ideas you bring in for everyone to work out.

Yes, but the fact is the guitar is such a strong element of the band now, and I’m very interested in how it's working, particularly what kind of ideas you bring in for everyone to work out.

BF: Well, in general we wanted to work more by composing while recording, so what we did for the albums before, usually, was write a whole bunch of material and go into the studio for four days and record it all. Instead we have a nice locale where we can record now, so we decided to record bits, and add overdubs and try out things. So it’s much more composing with the studio, with improv.

So you allow some flexibility once you get there.

BF: And I mixed it; so often I would add some overdubs while mixing, sending it to Pascal or Rémi to add some percussion or other important lines. So the pieces would grow in a different way than on the album before.

RL: We wanted to make something largely different from Avanti!

BF: Yeah, and so a few of the songs are improvised, recorded, then edited, then composed.

Added on after the improv. Interesting.

PG: The nice thing about it being a member of the band mixing the album, with someone like Bernard, is that the composition process is continued, and pursued, while mixing.

RL: And Pascal brings some ideas on the logic, software, and programming.

BF: Yeah, the other point is sometimes, Pascal or I or Rémi would bring more advanced compositions, and we used to bring only skeletons, in which everybody would find their own parts. But sometimes now Pascal arrives with more elaborate compositions, so I could play lines and I could compose.

Finally having seen you live — the counterpoint works, because there’s lots of opportunities for unisons, and then split into different counterpoints. That’s one of the beauties of the band. Having something very intricate like that, it takes time to be able to work that out. And I can see from the ends of the pieces and just the open spaces between different passages, just the amount of the first one, how much time you spent together.

Finally having seen you live — the counterpoint works, because there’s lots of opportunities for unisons, and then split into different counterpoints. That’s one of the beauties of the band. Having something very intricate like that, it takes time to be able to work that out. And I can see from the ends of the pieces and just the open spaces between different passages, just the amount of the first one, how much time you spent together.

PG: Sometimes we’d work on 30 seconds of a piece for a whole evening, around and around.

Yeah, because the transition, as you know, is essential to the piece, to the success of the piece. So thank you, I appreciate that.

RL: It was a good feeling yesterday when at the ends of the songs it was very quiet and they really [connected].

PG: There was a good listening quality in the crowd.

I can tell you that the main reason many people came to the [SeaProg] festival was to see Miriodor, because you haven’t been here before, and I’m of the same mind, myself. So what do you think are the best pieces, for how they turned out, after you completed them on the new record? Which are you happiest with?

I can tell you that the main reason many people came to the [SeaProg] festival was to see Miriodor, because you haven’t been here before, and I’m of the same mind, myself. So what do you think are the best pieces, for how they turned out, after you completed them on the new record? Which are you happiest with?

BF: Well, it’s a bit like asking a mother, "Which of your babies do you like best?"

[laughter]

Yes, because it’s the birth of your song, getting it out into its final form.

PG: Actually we were talking about that last night in the au pair room, and myself, maybe my favorite — but it’s hard to pinpoint or to choose one — is maybe "Tandem," even though that was the one we worked on first, and maybe is not the best-produced on the album. But it still may be my favorite.

BF: The composition is good. But the problem is it’s impossible to play it live. Definitely impossible. We would need a large ensemble. "Cobra Fakir" is one of my favorites. It sets the whole tone for what your album is going to be like this time. There’s no doubt about it, you guys have to challenge yourself one way or another each and every time to put out a recording. There’s just too much going on in your pieces not to think it out beforehand.

PG: Bernard and I, we challenge each other a lot in the process.

RL: I really enjoy "Maringouin." It’s more... it’s the easiest, maybe.

PG: I composed it and then I didn’t want to put it on the record because I thought it was too simple, maybe?

Nic said last night that some of the pieces are just fun. That’s one of the personalities that the group has that most bands flirt with, maybe just have one piece here and there, but you have it regularly on every album, several pieces that have a certain amount of whimsy to them, and which counter and work off the seriousness of the other tracks. It’s very good.

Nic said last night that some of the pieces are just fun. That’s one of the personalities that the group has that most bands flirt with, maybe just have one piece here and there, but you have it regularly on every album, several pieces that have a certain amount of whimsy to them, and which counter and work off the seriousness of the other tracks. It’s very good.

PG: We’re not a dark band.

BF: It’s true, often you go to a progressive music festival, and most of the bands are really dark, really serious. I like a sense of humor in life, and all those people usually in life are really funny people.

Oh, yeah, they’re very nice people. We spent some time with Present and Univers Zero band members. We’re very fortunate to have done that.

PG: They have an image that they cultivate I think. Because when you talk to Daniel Denis, he didn’t think that Univers Zero is that dark. For sure, those guys, when they look at their covers where they are all dressed in black, they must laugh a lot.

[laughter]

Can you associate a theme in Cobra Fakir? Because, you know, a lot of your albums — like I said, trying to describe your work can be a bit of challenge — but the fact is, there seems to be some kind of unification, a common thread, to a lot of your pieces, not just because of the arrangements.

PG: I don’t know if there’s a common theme. If there’s a general theme, I think it was done by Bernard while he mixed the whole thing, choosing sounds and choosing, placing, the atmospheres. I think it’s mostly due to him.

BF: The difference also is that Nic [Nicolas Lessard] wasn’t there, and the other Nic [Nicolas Masino] was gone, so I played all the bass, which happened in Jongleries Élastiques, where there are not so many bass tracks. Nicolas played a bit of bass, sometimes there are two basses.

PG: There’s no main theme, there’s no central theme.

BF: You realize after it’s done, like it’s a mold that fits together. But I guess it’s just that since we’re doing an album almost every four or five years, it’s a picture of ourselves at this time of our lives.

PG: Like a snapshot.

RL: Like, for the title of the album, the design of the album, it was not clear where we were going. It happened like that, finally. And it’s funny because we said once that we didn’t want the photo of us. It’s funny because I saw the Avanti! cover and the Cobra Fakir cover and there are some similarities.

BF: Next one, no picture!

RL: Focused and unfocused. But it happened accidentally, it was just the timing of it, it was not planned too much.

BF: No. For instance the Jongleries Élastiques record, we had the concept of circus.

Yeah, but that’s a common theme. I think unfortunately, early on, that theme was consistently placed on the band.

PG: I agree totally with you, because people think of us as a circus band, and we only did one record with that theme, but since then it’s...

...And it’s a wonderful record, though, I have to admit that I love Elastic Juggling. It’s a crazy record — because there are so many different things going on, you feel like you’re at a carnival a lot of the recording.

BF: It is overwhelming, yes.

PG: Myself, I’m a bit tired of that circus label. I’d like to move away from that.

That’s understandable. So, please tell us about your collaboration with Lars Hollmer. He’s someone who I hold in high regard, as well as a composer, just a wonderful man. How did you meet him and decide you were going to work together?

That’s understandable. So, please tell us about your collaboration with Lars Hollmer. He’s someone who I hold in high regard, as well as a composer, just a wonderful man. How did you meet him and decide you were going to work together?

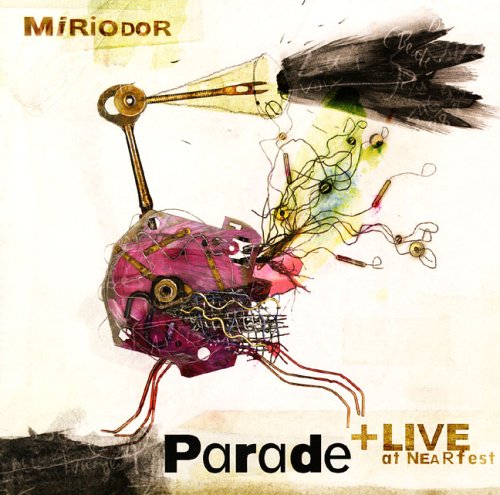

PG: It was for the Parade project. Rémi and I, and Bernard, we had a huge admiration for Lars and his work, and we had the idea — I am, and we were, a bit influenced by him also — so we had one or two pieces that we thought maybe we should try to contact him. And while he accepted to work on the two pieces, it was really difficult for him because what we sent him was already full. And what he succeeded in doing on pieces like "Frosted Bonsai" — the pieces were full, already full — but what he did was masterful on that piece. And after that we were lucky to launch the album in Portugal at Gouveia with him playing with us on a few pieces with Michel Berckmans. And also Lars at that time came quite a few times to Montreal so we met him a few times and we even played together at the FMPM (Le Festival des Musiques Progressives de Montréal), I don’t know what year. So that’s the general history. He was a charming man.

RL: Very nice.

BF: He also sent us a composition of his, which he hadn’t recorded, and we recorded it.

RL: Very, very friendly, very nice, easy to...

Easy to interact with.

RL: Yeah.

Your style is similar in approach, at times, to [Coste Apetrea]. He probably saw that.

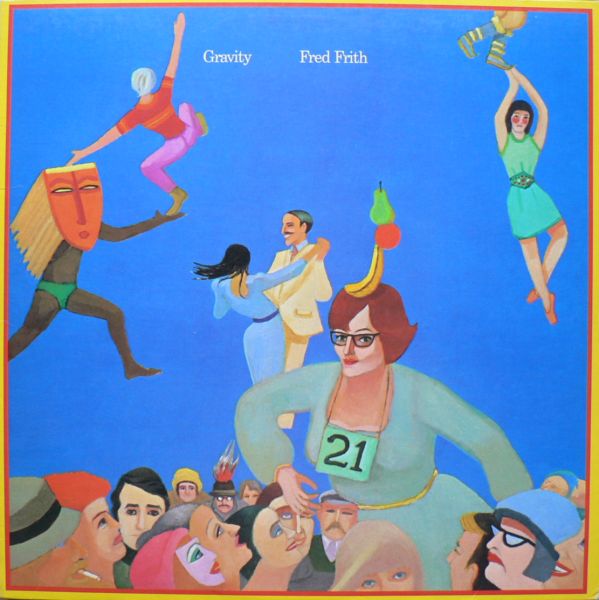

PG: I can’t say it’s a big influence but, I own a couple Samla records, I discovered them with Gravity, the Fred Frith album.

Frith usually goes on the team when he does collaborations. He gives the other artists complete, full range to do whatever they want because he’s trying to include that element of what they do. He doesn’t have to be the star.

Frith usually goes on the team when he does collaborations. He gives the other artists complete, full range to do whatever they want because he’s trying to include that element of what they do. He doesn’t have to be the star.

PG: I read somewhere that Frith chose that band because he liked them but also because they were extremely quick at picking up lines.

BF: To talk about Samla, he arrived at the Gravity sessions thinking that they were all readers, so he brought charts, and he was freaking out because they can’t read, most of them, and they said, “Play it once,” and he would play eight bar by eight bar and then they would all learn it real fast.

RL: Sabin Hudon, our sax player, was a big, big fan of them.

PG: And myself, I was a big fan as well. Do you have a question for Nic [Nicolas Lessard]?

Yes, I’ve been trying to get to that, so thank you very much. Nic, please tell us about what do you in the band, but first I also want to know, did you see the band first before becoming part of it?

BF: That’s why he agreed to come with the band because he didn’t know what he was coming into.

[laughter]

NL: No, to be frank, when I was approached by Rémi by email, I was about to go away for a couple of weeks in Toronto, and I said, "Yes I’m gonna listen to that." Because, shame on me, I didn’t know Miriodor at all. I had no clue! And I was quite shocked, and not only ashamed, but I felt that Miriodor deserved much more recognition, at least in Montreal, but then I understood that, yes, of course, the prog enthusiasts all around mostly are aware of Miriodor being there for so much time. But I cannot be approached as, let’s say, an expert interpreter, because I had to quickly absorb the aesthetic of the band, not only the bass lines. Because, yes, you have to learn them, you have to pick it up because it’s not written, and then also you have to make artistic decisions, because Bernard played some bass — especially on the last one, and another bass player, Nicolas Masino, played before, and they obviously had a very different approach with different results. And I had to sort of put myself in the situation where I would have to pick my own...

Interpret the lines you were going to play. Personality.

Interpret the lines you were going to play. Personality.

NL: Yeah. And I think it took a good six or seven months just to figure that out because options were various. What else? Well, you know, from the inside I was struck because I would have to pick up the lines, and some of them, since I have a background of classical music playing, I thought, yes, I’m gonna write some of it on paper/music. But then at some point I was puzzled because I would write a riff, and then I would figure out that it would be, let’s say, eight bars or so, and then I would listen after that to validate that and then to count the number of times it comes. And then "Oh, yeah," the first time, just like that, the second time, the same thing, but then, whoops, the third time there’s a bar missing...

Something different!

NL: "What the hell is happening here?" That was the difficulty, the challenge for me. But at the end I also think, now, that’s one of the forces of the band. Since the modus operandi, the way to compose most of the time, is by bringing some schemata to the other members, well, sometimes, as you mentioned, the counterpoints, the counterparts, the melody, they are added to that and they are often improvised, and they don’t always take into consideration the [structure], if you will. So, you know, you can have a theme that’s six bars, and then the bass riff is four.

RL: It’s elastic.

NL: Exactly. And to me, that’s a plus. That’s a keeper.

BF: The image I have of bringing a composition to Miriodor is like throwing a steak at a bunch of lions. [laughter] Because...

It’s going to turn out totally different than what you start with. Because everyone’s trying to find, what — ok, obviously there’s a great initial idea — but it’s like, "What am I going to do to take him out of this, how am I going to define and establish my turf? What are the things I’m going to own in this composition that are mine, right?"

BF: Yeah, add to it, twist it to make it different.

RL: Challenge the other with something.

Because it’s not just ‘show off,’ it’s more like, "Ok, well, now I see what you’re going to do," this is how the counterpoint part works, because "Oh, I see what you’re doing, I reply this." Not only the bass, but with the guitar you go through these other things.

Because it’s not just ‘show off,’ it’s more like, "Ok, well, now I see what you’re going to do," this is how the counterpoint part works, because "Oh, I see what you’re doing, I reply this." Not only the bass, but with the guitar you go through these other things.

PG: Yeah, the piece of meat thrown at the lion often ends up being a Caesar salad.

[laughter]

Oh, that’s great. That’s a great quote right there.

RL: I was surprised how fast Nicolas learned all the lines.

PG: Yeah he did a wonderful job.

NL: I must say, it did happen...

PG: What, it’s only bass, man.

[laughter]

NL: It did happen at a very good time of my life. Where, you know, I was sort of surfing on a certain, how to say, state of work, and I was having enough work anyway with the classical music, but I have a past including some rock playing and even adventurous...

RL: Crazy music.

NL: ...And I had to put it away for a little while, and it was a very, very welcome comeback for me to this.

Personally I just want to thank you for keeping the band alive. It’s obviously a personal thing for all of you to be able to do this. You do what you want to do and that comes through in every recording.

PG: Well that longevity is explained by the fact that there’s always been a key player coming in the band at a crucial moment. Like, Rémi came in early and is still with the band, and has been a driving force all these years. And when Sabin left the band, Sabin was a huge part of the trio that lasted for ten years, and we got Bernard who came in to replace him, who is a driving force as well.

NL: Actually we didn’t replace him.

PG: Well, yeah, they overlapped.

BF: I arrived at the moment where Sabin was losing a bit of interest. We worked as a four-piece for a bit.

PG: And after that Nicolas Masino came. He left, and six months later another Nicolas, Nicolas Lessard, came in, also an important member of the band now. So that explains the longevity.

RL: And there’s two things we depend on. One, I think, is Steve at Cuneiform, still, for a long time, a group partner.

We’ve been around a long time, too. Exposé was published in hard copy form since ‘93. We’ve worked with Steve from the beginning. Cuneiform is known internationally, because of his taste.

We’ve been around a long time, too. Exposé was published in hard copy form since ‘93. We’ve worked with Steve from the beginning. Cuneiform is known internationally, because of his taste.

BF: Oh yeah, it’s a great label because of that.

RL: He’s the boss and he does what he wants.

BF: He never had any artistic comments, wanting us to do something special. He says, "Ok, I let you do what you do." Which is great, which is the only deal we could accept.

RL: He can warn us about some details on the artistic view. And the other thing that can explain the longevity of Miriodor is in Quebec, the government support is essential for us.

PG: We got many grants over the years and the band wouldn’t exist anymore without all those grants. Because even despite the desire of the band members, we need some money, we need some support at some points.

BF: At the same time, for me, the only explanation of the longevity is because we’re having fun.

It’s just a good, consistent band. I mean, the albums are very different and the evolution of the band from the earliest...

BF: Watch, the next one is going to be very different.

Crazy? Very crazy?

RL: Yes.

BF: We’re just starting to talk about it. We haven’t started it.

Filed under: Interviews

Related artist(s): Miriodor, Bernard Falaise, Pascal Globensky

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Review: Steve Tibbetts - Close

Published 2026-02-28 - Release: We Stood Like Kings - Pinocchio

Updated 2026-02-27 19:24:02 - Release: Stephen Grew - Pianoply

Updated 2026-02-27 19:20:11 - Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Review: Mars Lasar - Grand Canyon

Published 2026-02-25 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25 - Release: Tashi Wada - What Is Not Strange?

Updated 2026-02-24 14:56:16 - Artist: Tashi Wada

Updated 2026-02-24 14:54:34 - Release: Greg Segal - Maintain!

Updated 2026-02-24 00:38:03 - Review: Il Segno del Comando - Sublimazione - Live

Published 2026-02-24 - Review: Nektar - Mission to Mars & Fortyfied

Published 2026-02-23 - Review: Jaime Rosas - Tres Piezas de Rock Progresivo

Published 2026-02-22