Exposé Online

What's old

Exposé print issues (1993-2011)

- 1 (October 1993)

- 2 (February 1994)

- 3 (May 1994)

- 4 (August 1994)

- 5 (October 1994)

- 6 (March 1995)

- 7 (July 1995)

- 8 (November 1995)

- 9 (March 1996)

- 10 (August 1996)

- 11 (February 1997)

- 12 (May 1997)

- 13 (October 1997)

- 14 (February 1998)

- 15 (July 1998)

- 16 (January 1999)

- 17 (April 1999)

- 18 (November 1999)

- 19 (May 2000)

- 20 (October 2000)

- 21 (March 2001)

- 22 (July 2001)

- 23 (December 2001)

- 24 (April 2002)

- 25 (September 2002)

- 26 (February 2003)

- 27 (August 2003)

- 28 (December 2003)

- 29 (April 2004)

- 30 (September 2004)

- 31 (March 2005)

- 32 (September 2005)

- 33 (May 2006)

- 34 (March 2007)

- 35 (January 2008)

- 36 (October 2008)

- 37 (July 2009)

- 38 (July 2010)

- 39 (Summer 2011)

Features

Proving It Every Night —

The Jamison Smeltz Interview

These days Jamison Smeltz can mostly be found with an alto sax in his mouth, off to one side of the stage with miRthkon, one of the bright spots in American progressive music. Heavy guitars meet woodwinds in miRthkon's complex music, and they've graced stages in North America and Europe at festivals including RIO (Carmeaux, France) and Seaprog (Seattle) — and that's just 2013. But before joining miRthkon, Smeltz played with a wide variety of other artists in a dizzying array of styles. I sat down with him after their performance at Seaprog in June 2013.

by Jeff Melton, Published 2013-11-24

photography by Danette Davis

Tell me about your first gig.

I finished college in ‘86, worked for a year and in late ‘87 I went to Europe and ran out of money after a few months. I had a horn with me and just started busking in the streets and I met musicians in Rome, who kind of took me under their wings and showed me how to be a street musician. About a month into that I met a girl who sang and played guitar and we started going out. We put material together and traveled together for about eight months. Through Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, Morocco, we were just playing in the streets and having a blast. After a year, we came back to the States and lived in Philly for close to a year, just working shit jobs, and finally got back to Northern California in late ‘89, and I decided to go back to music school.

I went to S.F. State for a year, and tried to get a degree in music. But I would have had to do two years just to get a second bachelor’s and I was like, “fuck that,” I got this offer to do this gig: it was called, “Columbia Artist Festivals presents A Tribute to Benny Goodman” (featuring Buddy Greco, Louise Tobin and Peanuts Hucko). It was 80 one-nighters in 90 days, on a Greyhound bus, with a 14-piece band. There were like four people in their 70s and 80s, and the rest of us were like late 20s early 30s.

I went to S.F. State for a year, and tried to get a degree in music. But I would have had to do two years just to get a second bachelor’s and I was like, “fuck that,” I got this offer to do this gig: it was called, “Columbia Artist Festivals presents A Tribute to Benny Goodman” (featuring Buddy Greco, Louise Tobin and Peanuts Hucko). It was 80 one-nighters in 90 days, on a Greyhound bus, with a 14-piece band. There were like four people in their 70s and 80s, and the rest of us were like late 20s early 30s.

The young guns and the really old timers. That’s hilarious.

We’d pull into a place at 4:30, do a quick sound check, get dinner, play from 8:00 to 9:30, go back to the Holiday Inn and everybody would try to pick up one of the cocktail waitresses. I’ll tell ya, it was an education in what I didn’t want to do with music, you know? I was pretty intimidated by a lot of those cats, including Jim (DeJoie) who plays with Moraine, he and his friend Matt were kind of the sax section leaders and they’d just gone through music school. On not only sax but clarinet and flute they were very strong, but I was such a horrible flute player. I had to play it up to do the gig, I even told the guy who hired me, “Listen, man, once they hear my flute playing they’re going to fire me.” And he said, “The tour leaves in two days. You’re not going to get fired. If you can do the tour, you’re on it.” Sight unseen this guy hired me. I don’t even know how he got my name after all that, but still. The tour started in L.A., and then went all the way out to Florida and then to Maine, and Chicago and then all the way back down to Texas again, in a very circuitous route. It was hard, man; that was an education. I came back from that and like, “OK, time to get a job.” I got a job at Odwalla and did sales for the juice company for about three or four years. And then I went to Brazil and I taught English for a year there. In the middle of all that I did a little playing in Salvador (Brazil) and hooked up with Jimmy Cliff, that was really cool.

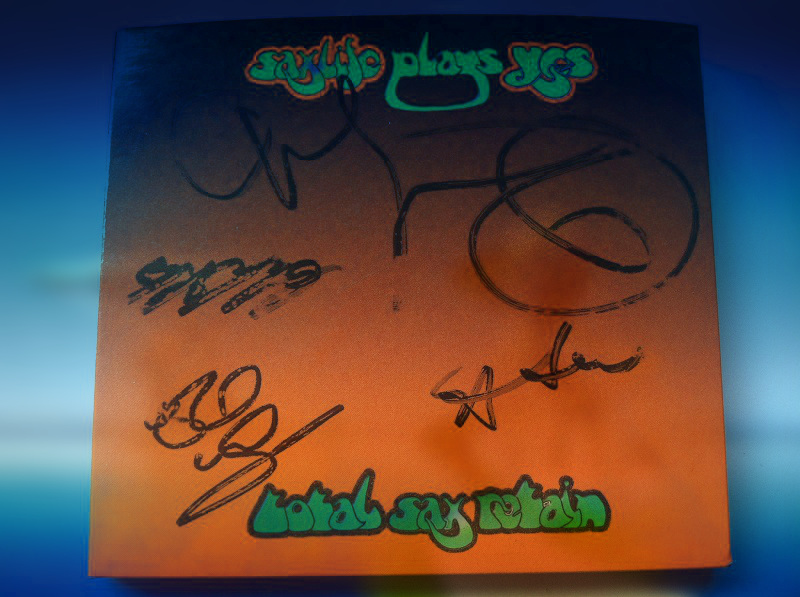

How long after that did you decide to record your Yes tribute, Saxlife Plays Yes: Total Sax Retain?

How long after that did you decide to record your Yes tribute, Saxlife Plays Yes: Total Sax Retain?

I went to Brazil at the end of Yes’ Talk tour, so I know it was 1994. I split with my first wife, the Italian girl I was playing with, and thought I was looking for the next one. I got to Brazil and knew after a few months that it was the wrong decision. I mean, I needed to get back here, figure it out in America where I know the rules and the phones work. That first trip to Europe was great because I was living out of a backpack and traveling everywhere. You know, I was 23 and the world was still open! The next one in South America was eight years later and I had an apartment, I was teaching English in schools in Rio de Janeiro, and it was just not nearly the little vagabond thing anymore, it was almost like a job. Let’s see, I came back ‘95, hooked up with Go Van Gogh again, who I’d played with on the other side, and then I started arranging the album around then. I think I did the first arrangement, which was “Turn of the Century” in ‘97 or ‘98, and started to flesh it out. You know, I didn’t even put the thing out until 2004. It was all in my living room and I wasn’t waiting for anything except to finish the damn thing. That’s how I learned to transcribe and do notation, and learned the software program Sibelius; all of that because of that album.

I listened to it not that long ago and it’s the arrangements that really stand out.

Well, they do. I appreciate that. It definitely sounds like some schmuck who recorded it in his living room, and it was.

Yeah, but from an artistic standpoint people listen and say, “Hey, here’s a completely different take on some familiar music.” That’s really fun.

I was happy with it. And in 2001 we played it at the Yescapade (fan gathering), live. And it was terrible. (Laughs.) It was fucking awful. I mean, I’d had half a dozen rehearsals with the guys and I know what this shit sounds like and what it’s not supposed to be like. It’s notated, and all you have to do is read it, but it still wasn’t enough. I’d love to do it again someday, I’ve found a couple players who’ve said they’d like to read it through again, but you know, it’s so 'been there done that' for me I’m just reluctant to go back and try to relive something that is... I’m such a prick with my own material, you know? I’m sure it wouldn’t be fun for anybody.

And not long after that you hooked up with Ten Ton Chicken?

And not long after that you hooked up with Ten Ton Chicken?

Chicken was ‘99; that’s been 14 years. Just after 9/11, I went and lived in the band house. It was a big fucking Partridge Family situation. It was where the band rehearsed and there was a room open, so I moved in January first of 2002, and four months later met my current wife Karla, we’ve been together over ten years. I joined Chicken in ‘99 and Casino Royale was ‘99; they’re a 60s Bacharach cover band. We have a few albums out including an original. Do you know the Fuxedos? Fuxedos was originally a Bay Area band, down in L.A. now, Lebofsky plays in it with me, or I play in it with him. Led by Casino singer Danny Shorago, it’s the bizarro-world version of anything nice.

No, you didn’t tell me about that.

Oh, that’s fucking insane. You gotta come check out the Fuxedos. Chicken and Casino Royale around ‘99, Fuxedos maybe 2004, Berkeley Sax Quartet in ‘06 and then in ‘07 when I went to see miRthkon and it was one of those religious moments, where it was like, “I want to fit in, I don’t know if I can fit in.” But I talked to Wally Scharold after the show because it immediately reminded me of Zappa and old Crimson. I didn’t even know there were horns in the band; I just remember saying, “We gotta go see this show; someone said it’s the real deal.” It was at the Uptown in Oakland and we were just like “Wha...?” And then a month later their alto player quit and Wally called me up and gave me an audition. That was ‘07, man, six years ago. And it’s still the hardest shit I’ve ever done and it’s the only stuff I’ve not been able to memorize. I just can’t. It’s like physically speaking words the wrong way. I mean, the endorphin rush, believe me, when you’re in the zone and you’re processing things so much faster than you’re supposed to be able to because of the speed of which it’s going on. A lot of it is a Hail Mary, you’ve just got to trust that instincts will get you through it, you know? And most of the time they do. Like, “That’s fast as fuck. And we’re nailing it.” All these guys I have no worries about, but my own personal part of it...

Oh, that’s fucking insane. You gotta come check out the Fuxedos. Chicken and Casino Royale around ‘99, Fuxedos maybe 2004, Berkeley Sax Quartet in ‘06 and then in ‘07 when I went to see miRthkon and it was one of those religious moments, where it was like, “I want to fit in, I don’t know if I can fit in.” But I talked to Wally Scharold after the show because it immediately reminded me of Zappa and old Crimson. I didn’t even know there were horns in the band; I just remember saying, “We gotta go see this show; someone said it’s the real deal.” It was at the Uptown in Oakland and we were just like “Wha...?” And then a month later their alto player quit and Wally called me up and gave me an audition. That was ‘07, man, six years ago. And it’s still the hardest shit I’ve ever done and it’s the only stuff I’ve not been able to memorize. I just can’t. It’s like physically speaking words the wrong way. I mean, the endorphin rush, believe me, when you’re in the zone and you’re processing things so much faster than you’re supposed to be able to because of the speed of which it’s going on. A lot of it is a Hail Mary, you’ve just got to trust that instincts will get you through it, you know? And most of the time they do. Like, “That’s fast as fuck. And we’re nailing it.” All these guys I have no worries about, but my own personal part of it...

But not everything you’re doing is in unison there is counterpoint stuff going on?

But not everything you’re doing is in unison there is counterpoint stuff going on?

But the unison is there. There’s a shout for us where we’re all in unison for about 32 bars something like that, in 6/4-12/8, and you’ll hear if anything is off. Yeah, you’ll like that; there are a lot of polyrhythms going on in there.

Let’s switch gears back to your upbringing: what saxophone great did you see and say, “Shit, I want to play that.”

Ah, well it wasn’t a great player so much as the very first time I saw a sax. I think we’ve narrowed it down to me being about three years old because we’re pretty certain it happened in Detroit. My family moved around every year my first six years of life; I started in California, southern California born, and then Fort Wayne, Indiana; Marion, Indiana; and then Detroit, then Knoxville Tennessee. So I was between three and four.

Wow, that’s a lot of miles!

Wow, that’s a lot of miles!

Well, my dad was a K-Mart manager and he was really good at what he did. They would always move him to a new store to get it back on its feet. Then he would fix it and move on to another store. And, you know, that was back in the days of company men when they would do whatever the company asked them to. It actually ended up being an amazing way to have a childhood, because it teaches you the impermanence of life and how to make friends and say goodbye to old ones and start all over again. I started over six times by the time I started grade school. And back to the first time I saw the sax: probably three, four years old, at a jam session. My dad was a jazz player and they would have friends over and just blow through standards, drink Ballantine’s and smoke cigarettes, shit like that you know? One day some cat had a tenor saxophone, and I still can feel it in the pit of my stomach where you see something that just makes you go, “Whoa...” you know, and sucks your breath away. And then it’s the combination of the line or lack of line. I knew right away that’s what I wanted to do. All the buttons and everything it just looked like science fiction — sex and science fiction. In the eyes of the three-year-old! So when I was about six my dad asked me, because my brothers had started school band, “What do you want to play when you grow up?” And I didn’t even know what it was called I said “I want to play the thing that looks like Old King Cole’s pipe.” That was my first musical hero.

Now as for legacy jazz greats, a lot of people start with Coltrane...

My first was Charlie Parker. I started taking sax lessons after I did four years of trumpet. Then in the middle of eighth grade I started sax lessons, I switched to sax at school and I hooked up with this amazing man who was a great school teacher but a pro sax player. He taught all the local high school kids in the area. They were all all-state, all of his jazz bands were all-state. I got in with Mr. Garton. And I remember when we called him he had a waiting list of like six months. And I was like, “Oh God, that’ll be forever,” but I kept working on my own and he had an opening in about two months. I got in there and I hit the ground running, man. I was eating the shit up like peanuts, because I was already reading pretty well but now I’d found an instrument I could respond to and that responded to me. Because with the trumpet, which I had played since fourth grade, you know, you’ve gotta buzz your own head to create a sound. Which just makes trumpet players crazy, man, I’m sorry, in general trumpet players are fucking goo-goo, I love ‘em but I couldn’t do that. But the reed vibrating and, you know, training your fingers to respond to the reality of a diatonic flute or something like that, just up and down. And then when you get the chromatic scale you train your fingers to accentuate the black keys, so to speak, of the saxophone. Then when you get it down it’s like boom, now you have it all, now have fun with it. My teacher gave me a lot of very challenging stuff and that really gave me a lot of game. I was all-state by ninth grade, I’d only been playing a year and a half and that was awesome. And I started learning Parker's solos via the Omnibook in ninth grade.

In your mind you weren’t thinking alto or tenor?

In your mind you weren’t thinking alto or tenor?

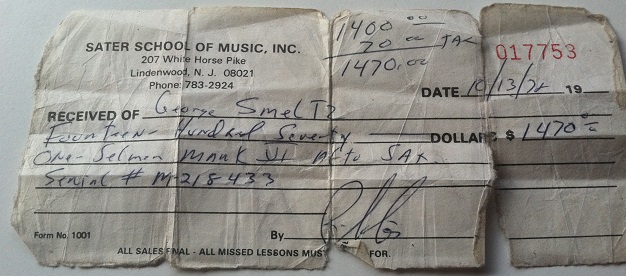

No, I wasn’t thinking any of it. Dad gave me my first horn, it was an alto because that’s usually what people will learn when they’re first starting. It’s the easiest, it’s the smallest, it’s the lightest and it’s the cheapest. And then once you learn alto it’s very easy to expand in any other direction. He got me this horn probably through K-Mart, he never ‘fessed up to that. One Christmas he came home with three horns. He got my brother John a new bass trombone, my brother George — what did he get George? A French horn, I think — and I got a saxophone. I’m playing on this really strange looking — it looked like a kid’s toy, it was a metal horn but it had this epoxy coating. It looked like a ‘57 Chevy with the gold trim. And the pads were made of rubber, I got to my first lesson with Mr. Garton and he looks at my horn and says, “I’ve never seen anything like that.” He was chuckling, he knew my dad was a player and my dad and he always had a good rapport. Here was my dad bringing in Jamie for a lesson and they were talking the gentleman talk, you know? After about a year or so we went in and Mr. Garton said to my dad, “You know, if you get Jamie a good horn who knows what could happen? Jamie’s got some skill there.” And my dad said, “Tell me what to get.” And the next week I got there and there were three Selmer Mark VI altos. I tried ‘em all and took the one in the middle. And Mr. Garton said, “Yeah, that was the best one.” And I got my horn, man. And that’s the horn I played last night. Thanks to that one beautiful piece of advice.

But so much of it is timing, and there’s a great deal of intuition that goes along with that, too, right? You’re searching for an outlet for your voice.

Somebody offers you a good horn, it’s like, hell yeah.

And it’s got to feel right, too.

It never felt right. I never had that really quiet confidence that people have when they become skilled right away at something. I mean, it took me 20 years to feel like “OK, I can pick this thing up and it’s going to do what I want it to do.”

You don’t feel like you’re an intuitive player?

Oh, I am now. But it took 20 years. Anyway, I got the horn. In 2007 my dad died, and I went down to Florida. We were going through his things. He’s really the man who gave me music. I mean, my mom was all really encouraging of it all but he was the weekend warrior playing trumpet and bass, and he took me along to dance band rehearsals as soon as I was big enough to hold a horn, you know? When he passed, we were down in Florida going through his things and I’m going through  a shoebox in the closet and it’s full of old receipts from the supermarket and coupons and folded in thirds is the paper that’s the receipt for my alto. Dated October 18, 1978, from Sater School of Music in Woodbury, New Jersey, and that’s where they got the horn and it’s $1,400 dollars plus $70 tax. And it says Selmer Mark VI, with the serial number on it. He kept that receipt the whole time. And I found it by freak after he died, going through a box of garbage. I got it in my wallet, want to see it?

a shoebox in the closet and it’s full of old receipts from the supermarket and coupons and folded in thirds is the paper that’s the receipt for my alto. Dated October 18, 1978, from Sater School of Music in Woodbury, New Jersey, and that’s where they got the horn and it’s $1,400 dollars plus $70 tax. And it says Selmer Mark VI, with the serial number on it. He kept that receipt the whole time. And I found it by freak after he died, going through a box of garbage. I got it in my wallet, want to see it?

Are you writing anything for miRthkon?

Are you writing anything for miRthkon?

No nothing. I’ve had this great melody, kind of Crimson-thing in mind called “Insectoid Earbud Bleed,” but I’m not a writer and I find the writing process very prohibitive. I’d rather work on some lead sheets or teach a class or work with kids. I’m not at all a prolific writer, I’ve written maybe five, six things in my life. I did some good arrangements recently, I recently arranged Yes' "To Be Over" for the youth wind ensemble I run (Winds across the Bay). It’s a non-profit.

The thing that saddens me is that I actually did a session for Jon Anderson with Steve Stone. Here’s what I believe of what I know of that’s happened so far: this guy Steve Stone contacted me through our mutual friend Gary Worsham, who I played with in D*FeX in college and is an audio engineer, and said that he’s doing some work for Jon. Jon is looking for some revamped revisions of old Yes songs. And Steve's doing “Long Distance Runaround,” and one other...

Did he know about the Saxlife disc?

Jon? Yeah, I gave it to him in 2004 when I went to England after I released the disc and followed Yes for a week. So, I went to Steve’s house and played these parts, it was a lotta fun, did a whole bunch of different takes. Oh, and "Then" was the other song. That’s what he said, he’s like “Arrange it and do whatever you want with it,” and I had like eight sax parts going through it, it was fat. Anyway, the long and short of it was, he’s like, “OK, the files are going to Jon.” I’m like, “Great. Hey, man. I want to send an email to Jon; can you pass that on for me?” And he said “Yeah, sure.” I’m like, “Hey Jon, it’s Jamison again. We’ve met a few times; I released the Saxlife album of Yes’ music. I’d love to get in touch with you, I know you’re coming to town, I’d like to hear from you, say hi.” And nothing, he never responded. And I talked to the guy who forwarded the thing and was like, “You did send the email?” And he’s like, “Yeah, Jon got your email.”

And then when I did this last arrangement, John Costello contacted me and he said “You should see if Jon Anderson will Skype with you. At the concert, people can ask him questions.” Cause I was going to do "To Be Over." It’s such a beautiful song. You know what really surprised me is when they did “Turn of the Century” in 2005... they didn’t gel. There was not enough listening within the band.

I can tell you having seen them here, do that piece, the new singer Jon Davison completely embraced it.

I can tell you having seen them here, do that piece, the new singer Jon Davison completely embraced it.

Well they sound a lot more true to the original source, with today’s voices, than others tours. Much more like, “Let’s listen to this and recreate an album, bitches. Do it.”

If you’re looking for my confirmation that the band is back, I can tell you, with the new singer something has happened; something significant.

Exactly, do what you can with what you got. And don’t fucking apologize for it. I hear many players with major game and you try to talk to them, and it’s the self-deprecating, “Oh, no...” And how much of it is sincere, and how much of it is kind of like expected affectation? A lot of people are really down on themselves who are at a really high level in their game...

But it’s not based on what they do it’s based on what they’ve experienced, and also there’s some expectation, like, “Damn, I know I’m good, but the fact is I don’t gotta prove anything now.”

But you always do. You always have to prove everything. First of all you have to prove it to yourself, but every time you perform you’re putting your energy into a momentum and adding your piece to this whole, cruising down the road between 40 and 300 miles an hour, and you have to hang on with your toenails, because all the rest of you are moving towards creating that end that is the epitome of your prowess, your game.

But you contribute your part, and as you know, having played with miRthkon for a while now, the sum of the parts can be much greater than the whole, it may not be twice or three times but the fact is when it happens it’s like, “Oh my God, I delivered my part, how could it all sum up to this?”

Let me tell you about last night.

Let me tell you about last night.

That was a really great gig.

I appreciate that. We went to dinner and all of us had wonderful food made with great attention. It was the perfect little salad with fresh spring greens, with a little bit of tomatoes on top, the French-dipped sandwich with prime rib. It was awesome and the camaraderie of hanging out and everything, then we got back to the hotel and two people left for the airport right away. Had to catch a 3:40 a.m. shuttle, and then three of us went back to the room and I’d recorded the show on my Zoom with just the house mix, you know, put it up by the soundboard, and we’re like, “Let’s listen to this!” And we get back to the room and there’s a built-in speaker, and there’s an 1/8-inch out but there’s no 1/8-inch input into the typical television. They still have RCA jacks and they’ve even got USB but they don’t have an 1/8-inch in. And we’re also thinking, “Man, it’s like 3:30, we’re going to be loud. let’s just go back out in the van.” And from the very first song, we were (I want to say) transformed, in the sense that we sounded unlike we’ve ever sounded live, also with an ambient mix.

It’s a good venue, it sounds good, right?

Yes, but beyond that we’ve finally gotten rid of all our amps on stage and all of our wedge monitors, we all have in-ear monitors now which we control, we do our own mixes, individually. And the horns are almost there, he’s got to dial in the EQs on the clarinet and bass clarinet and those are still the hardest things ever to really get decent.

Well, the bass clarinet was really good last night.

It’s hard to mic one of those motherfuckers. But listening to the show, I heard stuff I’ve never heard before. And I’ve been in this band since ‘07 now, six years. And I’m now hearing how the larger wholes are forming in, because there’s always two or three instruments moving in either harmonic or melodic unison. I’m starting to get a little larger view of Wally’s vision as a creator and writer of music. There were expanded levels of nested quintuplets going on.

Well, the guitar players have such a great chemistry, I noticed that right away, but also Wally has his particular parts and then he relies on Travis.

Well, the guitar players have such a great chemistry, I noticed that right away, but also Wally has his particular parts and then he relies on Travis.

Travis is the baby, now. He’s going to be 30 in January and I’m going to be 50 in February, we got 20 years between us. There’s five to seven years between me and Lebofsky and Guggemos, and then Wally’s another seven behind that, and then Carolyn...

That’s the younger part of the band, right? They’re really digging what you guys are doing, though, in fact everybody is really into it.

They’re world class at what they’re doing already.

Well, the whole band is really pulling for everybody on an individual and a collective basis.

Well, we can hear what we’re playing and how the parts fit together without being pummeled by something that is not us. And I don’t mean pummeled, but how loud the guitar is on stage, it’s almost impossible to get over that.

But the mix can be really fatiguing, right? And not only are you trying to do your part and get through the set, but you’re trying to hear what else is going on. You want to enjoy what it is you’re doing at the same time.

For me, the enjoyment comes later. Because you’re at such a heightened sense of awareness, alertness. You’ve gotta be responding at 110 percent.

Special thanks must go to Regan Crisp for transcription and editorial help.

Filed under: Interviews

Related artist(s): miRthkon

More info

http://www.tentonchicken.com

What's new

These are the most recent changes made to artists, releases, and articles.

- Review: LeoNero - Monitor

Published 2026-03-04 - Review: Sterbus - Black and Gold

Published 2026-03-03 - Release: Janel Leppin's Ensemble Volcanic Ash - Pluto in Aquarius

Updated 2026-03-02 15:06:51 - Release: Janel Leppin - Slowly Melting

Updated 2026-03-02 15:05:27 - Release: Alister Spence - Always Ever

Updated 2026-03-02 15:04:11 - Release: Let Spin - I Am Alien

Updated 2026-03-02 15:02:41 - Review: Falter Bramnk - Vinyland Odyssee

Published 2026-03-02 - Review: Exit - Dove Va la Tua Strada?

Published 2026-03-01 - Review: Steve Tibbetts - Close

Published 2026-02-28 - Release: We Stood Like Kings - Pinocchio

Updated 2026-02-27 19:24:02 - Release: Stephen Grew - Pianoply

Updated 2026-02-27 19:20:11 - Release: Thierry Zaboitzeff - Artefacts

Updated 2026-02-27 00:16:46 - Review: Kevin Kastning - Codex I & Codex II

Published 2026-02-27 - Release: Zan Zone - The Rock Is Still Rollin'

Updated 2026-02-26 23:26:09 - Release: The Leemoo Gang - A Family Business

Updated 2026-02-26 23:07:29 - Release: Ciolkowska - Bomba Nastoyashchego

Updated 2026-02-26 13:08:55 - Review: Immensity Crumb - Chamber Music for Sleeping Giants

Published 2026-02-26 - Release: The Gatekeepers - Diary of a Teenage Prophet

Updated 2026-02-25 15:55:58 - Listen and discover: Mordecai Smyth will not break your back

Published 2026-02-25